Daniel Rapaport

You’re sitting on your couch on a Sunday afternoon, scrolling through Twitter during a break in Golf Channel’s coverage of that week’s PGA Tour event. You mindlessly race through your feed before a certain blond-haired junior golfer catches your eye. He’s everywhere. Seems like he’s a pretty big deal.

His name, you learn, is Jackie Nicklaus. He’s 16 years old, and he just used a third-round 64 to beat a field of professionals and win the Ohio Open. The victory takes him to No. 1 in the Rolex/AJGA rankings, and rumor is Ohio State has the best chance of landing the Columbus native.

Here’s the part where we state the obvious: Nicklaus was never in the AJGA rankings because the AJGA didn’t exist when he was a junior. He was never featured on Golf Digest’s Instagram account at age 16 because Instagram wasn’t created until Nicklaus was 70.

But he did shoot that 64 and win the 1956 Ohio Open as a 16-year-old, and he most certainly was the best junior golfer in America. As the Golden Bear’s 80th birthday approached, we got to thinking: What would Nicklaus’ career have looked like if he came to prominence today, in this age of $12 million purses and TrackMan and Twitter?

Of course, this undertaking is meant as a fun exercise into alternative reality; it is not possible to accurately predict how Nicklaus would have developed or measured up to today’s professionals. It’s a thought experiment supported by the limited data available. Nothing more, nothing less. And yet, indulge us in this look at hypothetical history.

AMATEUR CAREER

The potent combination of Instagram, wall-to-wall TV coverage and the Internet has turned junior and amateur golfers into niche celebrities. The U.S. Junior is broadcast nationally, as is the U.S. Amateur and a few elite college tournaments. Back in Nicklaus’ day, if you played well in a junior tournament, the best you could hope for was a write-up in the local paper. Today, the country will likely see it.

But that’s not the only way to become something of a household name (at least in golf households). All it takes is one person, at one tournament, to post one swing video and post it into the Instagram/Twitter vortex. Or you can do it yourself. A little self-promotion can yield heaps of followers. And the social-media hype train needs but the smallest nudge to leave the station. We dissected the physics of Matthew Wolff’s swing before he ever played a PGA Tour event, and we could identify Akshay Bhatia’s bespectacled face before he turned 18. (He still hasn’t turned 18.)

Both those players accomplished much before they turned professional, but their amateur résumés don’t come close to being as stout as Nicklaus’. Part of the reason is, they both turned pro before age 21—more on that in a second—and so didn’t have the time to accumulate as many accolades. A bigger part of that, however, is because Nicklaus was one of the best amateurs of all time. Simply put, he would have been an ultra-phenom had his rise happened today. Consider this incomplete chronological list of some of his accomplishments before turning pro:

• Won five straight Ohio Junior titles, beginning at age 12 in 1952

• Won the 1956 Ohio Open against a field of professionals at 16

• Won the 1957 International Jaycee Tournament

• Qualified for the 1957 U.S. Open at 17

• Finished 12th in his first non-major PGA Tour event at 18

• Won the 1958 Trans-Mississippi Amateur

• Won the 1959 Trans-Mississippi Amateur

• Won the 1959 U.S. Amateur, the youngest champion at the time at 19

• Won the 1959 North and South Amateur

• Tied for 13th in the 1960 Masters at age 20

• Tied for second at the 1960 U.S. Open; his 282 was the amateur record for an Open before Viktor Hovland broke it in 2019

• Tied for seventh in the 1961 Masters

• Won the 1961 NCAA Championship

• Won the 1961 U.S. Amateur

• Tied for fourth in the 1961 U.S. Open

The World Amateur Golf Rankings didn’t exist in the late 1950s/early 1960s, but you can bet this and next month’s rent that Nicklaus would have been a strong No. 1 for at least two years. Golf Digest named him the world’s top amateur golfer for three straight years. Such a sustained run as the world’s best non-professional is unheard of these days because phenom-level American or international college players usually turn professional before receiving their degree. (Nicklaus did four years at Ohio State but finished a few courses short of a degree; he was granted an honorary one in 1972).

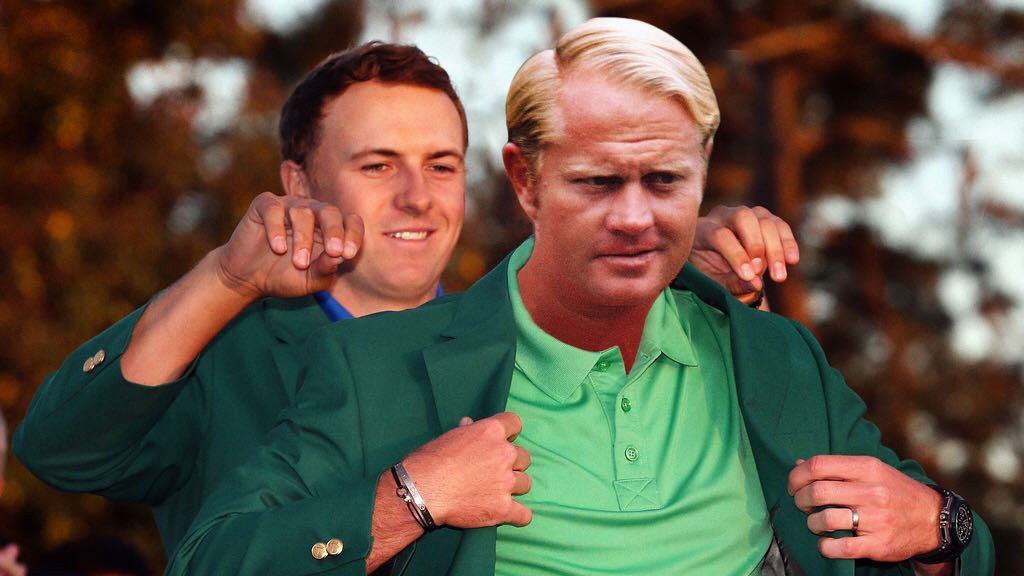

Wolff did two years at Oklahoma State, Bhatia turned pro at 17, Jordan Spieth spent one season at Texas, Justin Thomas was at Alabama for two years, Tiger Woods two years at Stanford. It’s different these days, due in no small part to the fact that these guys know they want to be professionals from a young age. It’s a lucrative profession these days, and it wasn’t always that way. In Jack’s day, the money simply wasn’t the same, so turning pro wasn’t the no-brainer it is now. It wasn’t until 196 , after he’d finished T-2 and T-4 in the 1960 and ’61 U.S. Open as an amateur, that he decided playing golf was a better option than selling insurance. It’s worth wondering if Nicklaus—knowing not just that he could make millions with his play, but that he’d also sign lucrative endorsement deals upon turning pro—might have left Ohio State early had he been in the Class of 2021, not 1961.

DRIVING DISTANCE

For those of us who grew up in the 2000s, our image of Jack Nicklaus is, well, that of an older gentleman. We appreciate his 18 professional major championships, but we never watched the golfer who won those tournaments. Even the 1986 Masters is highlight-reel fodder. The only tee shots we’ve seen him hit at Augusta National are of the ceremonial variety.

It can be hard, then, to picture Nicklaus as the longest player on the PGA Tour. But that’s exactly what he was in his heyday. Consider this: In 1963, Nicklaus won the long-drive contest at the PGA Championship with a 341-yard blast. “That drive was 341 yards, 17 inches. I do remember that, too,” he told Golf Channel in 2013. “That was an 11-degree wood driver, 32.75 inch Dynamic Edge shaft.”

Max Homa won the PGA Championship long-drive contest in 2019 at Bethpage Black with a 318-yard shot, but that came on a cold and wet spring New York day. The year before, in the throes of a St. Louis summer, Bryson DeChambeau, armed with his optimized launch angle and state-of-the-art driver and ground-force maximizing swing, hit one 331 yards to win.

Speaking of that 1963 PGA Championship, Nicklaus won it. He often overpowered courses much in the same way today’s longest hitters do, and he did so that week. Here is Sports Illustrated’s description of the performance, one that could be copied, pasted and published in 2020 without anyone knowing how long ago it was written.

“He rarely had to take anything out of his golf bag but his driver, wedge, putter and towel. … Meanwhile, just about everybody else, including [Dick] Hart and [Shelley] Mayfield, was wilting in the heat like a yellow rose of somewhere.”

Clearly, Nicklaus had a physical and length advantage over his competitors. But just how long would he have been with today’s equipment and technology? If you take Lee Trevino for his word: freakin’ far. “If Jack in his prime could have played the clubs and balls these guys are playing today, he would have hit that sumbitch 400 yards,” Trevino told Golf Digest in 2010, with characteristic color. “I’m dead serious.”

A search for a more scientific answer is hamstrung by a lack of data. There was no ShotLink in the 1960s or ’70s, and the first year the PGA Tour kept driving distance as an official stat was 1980. Luckily for us (and somewhat randomly) IBM did, for whatever reason, decide to measure driving distances for 11 tournaments in 1967, when Nicklaus was 27 and in his physical prime. The results, as uncovered by our Mike Johnson: Nicklaus averaged 276 yards, the longest on the PGA Tour. He was 4.5 percent longer than the average distance of 260.2. Extrapolate that 4.5 percent advantage to the 2018-’19 season, when the average was roughly 293.8 yards, and a player with Nicklaus’ advantage would have averaged 307 yards.

But there’s another relevant data point here, and it paints a slightly different picture. Nicklaus was 2.15 percent longer than the rest of the top 10, meaning there was a bit of a gap between he and the next-longest players. If we translate that advantage to last season, he’d have averaged 318.71 yards, which would have led the tour. So if we average those two figures—307 yards and 318.71 yards—we get 312.9 yards. That would have ranked fourth on tour last season, ahead of bombers like Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka, Tony Finau, Gary Woodland and so many more.

But even that feels like a conservative estimate. Nicklaus never had his swing speed measured during his best years. In fact, he didn’t have it measured until he was a Champions Tour veteran. In his words, via a Golf Digest article from 2015: “First time I ever had my swing speed checked was ’98. I was 58, and I was out at either Titleist or Callaway … and I was 118 miles an hour. And I said, ‘Wow, that’s pretty good, I guess.’ ”

Pretty good, indeed. A 118-mph clubhead speed would have ranked around 38th on the PGA Tour in 2019, and Nicklaus was nearing Social Security retirement age when he swung it that fast. You have to think he would have had a few extra MPHs when he was a younger man. While we’ll never get a precise answer, it’s safe to assume Nicklaus would have been Rory McIlroy-type long were he playing today.

EARNING POTENTIAL

Scroll down the list of the PGA Tour’s all-time money leaders. Keep scrolling. Keeeeeep scrolling. See it yet? There, nestled between David Peoples and Michael Bradley, you’ll find the name Jack Nicklaus, ranking No. 293 in career earnings with $5,734,031. C.T. Pan, Hudson Swafford and Morgan Hoffmann are among the numerous less-than-Hall-of-Fame-calibre players who have earned more on tour than Jack.

Anachronistic comparisons like that one don’t tell us much beyond what we already know: inflation and a purse explosion make the life of today’s middling PGA Tour player much, much more comfortable than the life of a middling PGA Tour player in 1972. We choose that season because it was maybe the best of Nicklaus’ career—he won seven times, including the Masters and the U.S. Open. Here’s what he earned for each of those victories:

Bing Crosby National Pro-Am: $28,000

Doral-Eastern Open: $30,000

The Masters: $25,000

U.S. Open: $30,000

Westchester Classic: $50,000

U.S. Professional Match Play Championship: $45,000

Walt Disney World Open Invitational: $30,000

For the season, Nicklaus won $316,911. That led the money list by 52.9 percent over Trevino, who was second with $207,255. Last season, McIlroy finished second on the money list with a total of $7,785,286—52.9 percent more than that total is $11,903,702, which serves as a ballpark estimate for what Nicklaus could have earned if he had a 1972-like season in 2019. That would rank as the second-highest single-season total in PGA Tour history, behind only Jordan Spieth’s 2014-’15, though it should be noted that the actual second-highest total belongs to Vijay Singh in 2004, which also would have netted more had it happened later.

Of course, on-course earnings account for a fraction of what today’s most popular players earn off the course. Nicklaus had an endorsement deal with MacGregor Golf, and he played the manufacturer’s clubs and balls during all 18 of his major victories. He also collected paychecks from non-equipment companies. But the endorsement climate was hardly as lucrative (or as mature) as it is today. So how much ish, could an in-his-prime Nicklaus have earned as a “brand ambassador” in 2020?

“Let’s take a [Phil] Mickelson, or a Tiger, and look at it from that perspective,” says Eric Smallwood, president of Apex Marketing Group. “Jack’s definitely up in that echelon. If he was having the success he was having in this day and age, he’s in that super-high echelon. Those are the only two guys you could compare him to.”

According to Forbes, Woods earned $54 million in endorsements in 2019, and Mickelson’s sponsors paid him $36 million.

“You think of all the companies that he could endorse,” Smallwood says. “Telemetry companies. Technology companies. … One of the things that he probably never had the opportunity to endorse is the influx of the shoe and apparel endorsement companies. There were some out there, but the money he could have earned with a Nike—those just weren’t there.”

So there you have it: Had Jack Nicklaus played today, he would have been an amateur phenom, he would have been one of the longest hitters on tour, and he would have made boatloads of money. He was great then and he would be great now. Sounds about right.