A statistical breakdown suggests Phil could finally complete the career Grand Slam at Pebble Beach

By Joel Beall

Pebble Beach sits off 17-Mile Drive, but for Phil Mickelson, the course is at the fork of divinity and despair. Pebble is hosting the U.S. Open, the championship that’s painfully eluded Mickelson. His relationship with this event, while not the dominant element of his career story, is definitely in its first paragraph, and the chances to rewrite it are dwindling.

Mickelson will turn 49 on U.S. Open Sunday. That’s 21 years older than the average Open winner in the past quarter century. It’s also an event that has given him fits during the last decade, as he owns a lone top-25 finish (a runner-up in 2013) since 2010. Coupled with last year’s quick-rake on the 13th green with his putter during Saturday’s third round and a recent rip at the USGA, one could opine Mickelson has come to accept that it’s not going to happen.

Though that may be his ultimate fate, this year offers a final shot. He was born and lives in San Diego, but Mickelson has made Pebble his home. He’s won the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am a record-tying five times after winning there earlier this year. He additionally has two runner-ups since 2016 at the Crosby Clambake to go with a T-4 at the 2010 U.S. Open on the grounds.

Then there are parentage roots: His grandfather, Al Santos, was one of the first caddies at Pebble Beach. Mickelson still uses a silver dollar from Santos as a ball maker for luck.

“I have such great memories here,” Mickelson said in February on his Open-at-Pebble prospects. “I would love to add to it.”

So could this be the year golf’s Charlie Brown, at his spiritual safe place, kicks that elusive ball, or is it ripe for Mickelson to be on his back once more? Putting aside cosmos and karma, a dive into the analytics show a roadmap where Phil may be left standing come Sunday’s end.

Harry How

There are promises in Mickelson’s corner.

The U.S. Open is said to be the last bastion of accuracy in the bomb-and-gouge era, both in drive and approach. No matter the venue, finding the rough off the tee means a battle for par and missing the green means much worse. It’s why the U.S. Open boasts the highest score relation to par of all the majors, with 3.84 under the average winning number this century. Subtract the 16-under aberrations at Congressional and Erin Hills, along with Tiger Woods’ historic romp in 2000, that accounting drops to 1.66 under. Power matters, sure, but it’s useless without precision.

At least, that’s the reputation. The stats show that’s not always the case, not to the degree one would expect from the box. In the last 19 U.S. Opens, the cumulative average of fairways hit is 65.97 percent for winners compared to a 60.19 mark for the field. An advantage, but not one of significance. Moreover, though it’s a small sample, that variance has been nonexistent at the last three U.S. Opens at Pebble, with Tom Kite, Woods and Graeme McDowell owning a collective 66.63 fairway percentage to the field’s 65.29 figure.

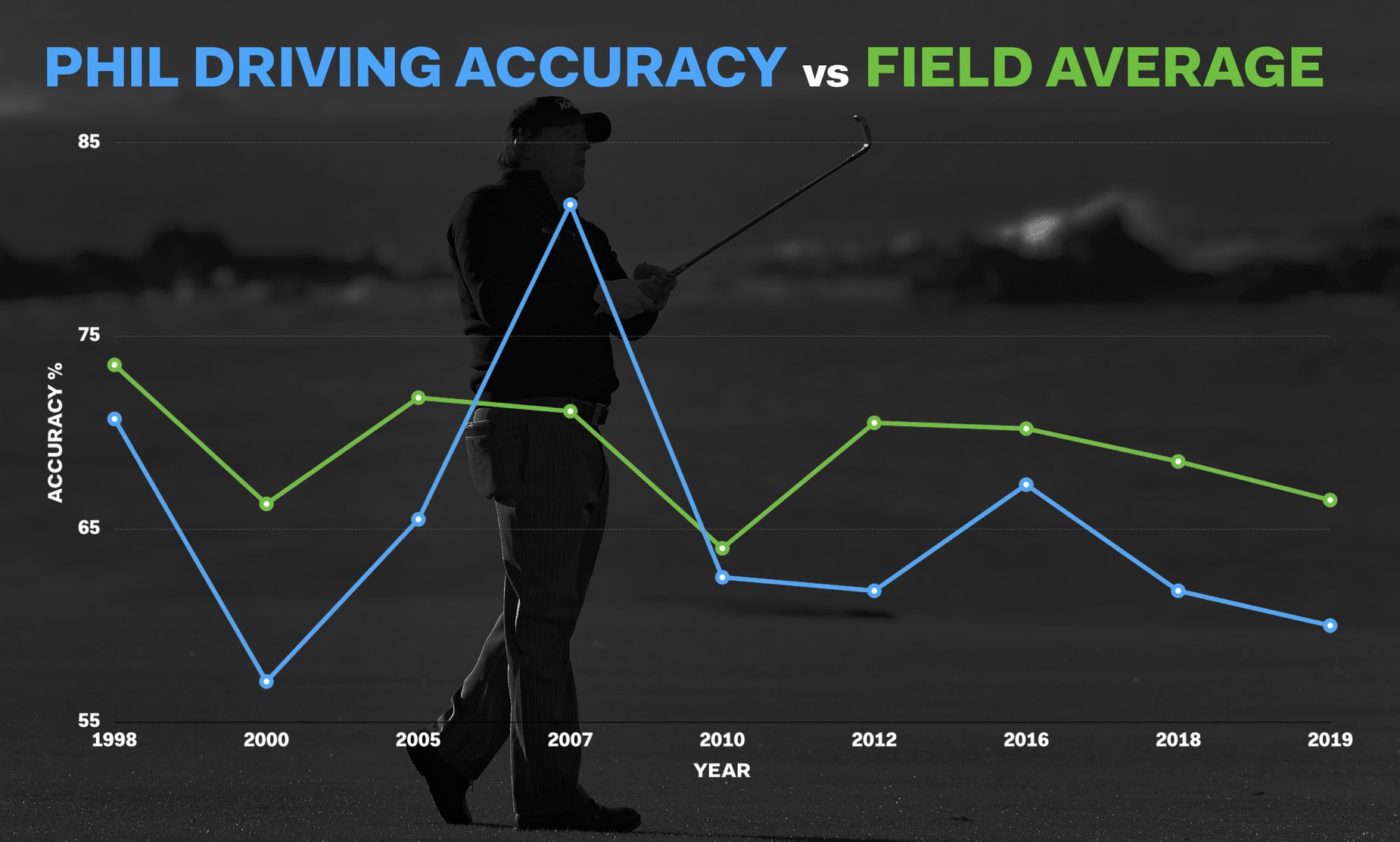

Music to Mickelson’s ears, and a tune he likely knows. Keeping it straight has never been his speciality, yet 2019 has been a special kind of awful, ranking 206th in driving accuracy. That hasn’t mattered in his dealings with Pebble. In four of his five Pro-Am wins and both of his runner-ups his driving accuracy has been worse than the field’s, averaging a middling 65.85 percentage in those strong performances versus the field’s 69.18 percentage.

Granted, the set-ups are far from apples-to-apples: One frustrates the game’s best, the other helps Ray Romano break 100. Nevertheless, subpar-driving marks didn’t submarine Mickelson at the 2000 (T-16) or 2010 U.S. Opens (T-4). Below are Mickelson’s accuracy percentages for his best seven finishes at Pebble Beach, along with his two U.S. Open appearances.

How has Mickelson excelled in spite of his waywardness? Simple: Mickelson’s been one of the best approach players from the high grass over the last decade, ranking 16th or better five times in rough proximity. Even this season, which has been a bit of a struggle (more on this in a moment), he ranks 28th in the category, and sixth from the right rough.

Important, because while the U.S. Open’s reputation for keeping it in the short stuff is slightly overblown, it’s notoriety on second shots is well-earned.

In the aforementioned 19-year time span, U.S. Open champs own a 68.49 greens-in-regulation percentage, a number that dwarfs the event average of 55.54. The disparity is relatively the same during the 1992, 2000 and 2010 U.S. Opens: 61.11 winner’s GIR percentage versus 50.62 for the field.

At U.S. Opens over the last decade, Mickelson—in spite of the lone top-25 finish since the tournament last visited Pebble—has been solid in this facet, owning a 61.30 GIR percentage. But that figure soars at Pebble to 71.45 percent. Again, distinctive set-ups … but not so distinctive where differentials like this are thrown out. Clearly, the course speaks to him.

Because it’s not just where you’re hitting the approach, but how far. Which is where Pebble, more so than other Open sites, lends a helping hand.

Sean M. Haffey

Pebble is expected to play 7,075 yards, with only Merion—where Mickelson finished second—having been a shorter U.S. Open venue in the last nine years. Not that Mickelson lacks pop by any means; he’s 16th on tour in distance in 2019. However, while the onus on finding the fairway is slightly overblown, it’s still advantageous. And for Phil, the shorter the club in hand, the better.

“You really don’t need to hit a lot of drivers,” Mickelson said about Pebble. “So it gives me a chance that—it lessens my weakness, which is hitting fairways.”

It’s at this point we should mention Mickelson, just 10 days removed from this statement, announced plans to carry two drivers. Equipment choices aside, why Mickelson is so deadly at Pebble Beach is the distances he leaves himself for his second shot.

Pouring through Mickelson’s shot trails through the PGA Tour’s database (which begin in 2003), a pattern emerges: by strategy or serendipity, Mickelson routinely faces approaches of 135-140 yards and 155-165 yards at Pebble. Yardages where Mickelson is perennially an assassin.

In the last decade Mickelson has ranked inside the top 25 in approaches five times from 125-150 yards, including a standing of sixth this season. Same goes for 150-175 yards, ranking ninth in 2019. Oddly enough, despite his short-game wizardry, his numbers from inside 75 yards and 125 yards aren’t as robust.

Essentially, Pebble is tailored to Mickelson’s optimal ranges. And they are ranges Mickelson should see at the U.S. Open, as the tournament will only play 120 total yards farther than February.

Chris Trotman

Of course, while strokes gained has proved the importance of the iron game, it doesn’t mean much if you can’t convert on the greens. With five Pro-Am titles to his name, it’s no surprise that Mickelson is comfortable on Pebble’s.

“You need to putt Poa annua greens very well with a lot of break, which is something I’ve done well,” Mickelson said.

Mickelson is one of the game’s streakiest putters. In the last decade, he’s ranked 13th or betting in strokes gained/putting three times. He’s also finished outside the top 130 three times, with a handful of 40th and 50th places in between. He’s as fickle with the flat stick as they come.

Except at Pebble. He’s one of the top putters each year on the peninsula, with a plus .671 strokes gained since 2009. For context, Greg Chalmers had a tour-best .790 strokes/putting mark last season; Mickelson’s Pebble output would have been seventh.

He’s not been as prosperous during the U.S. Open. According to Shotlink, Mickelson has a negative -.637 in this span at the national tournament. To be fair, U.S. Open greens are the toughest players combat all season, while Pebble’s surfaces are decidedly on the other side of the spectrum (again, catering to the amateur and celebrity ranks). It’s also logical that a player would have better production on greens he sees annually versus a changing venue.

Conversely, for a guy who was driven to insanity on Shinnecock’s greens, Pebble’s, even with a tad more speed, will be a welcomed sight.

• • •

Before placing wagers on Mickelson, there are a host of red flags.

He hasn’t been relevant on the big stage for quite some time. Save for his epic duel with Henrik Stenson at Troon, Mickelson doesn’t have a top-15 finish in his last 16 majors. He’s also not so much storming into Pebble as stumbling. The 48-year-old has missed the weekend in five of his past eight outings, and finished a distant T-71 at the PGA Championship. He’s 96th in strokes gained, 77th in tee-to-green.

Then there is his age. The Open Championship will entertain an elder statesman in contention; but not the American variety. Only twice has a player older than 35 won in this millennium.

There will be more chances, but Winged Foot will be too long, its greens too complex, in 2020, and the rough at 2021 U.S. Open host Torrey Pines has become so brutal that Mickelson has stopped playing the Farmers Insurance Open, his hometown event.

In short, this appears to truly be Mickelson’s last shot.

The idea that the 28th time’s the charm for Mickelson seems farfetched. Yet, while despair appears on the horizon, the stats prove divinity remains in play.