By Robbie Greenfield

By Robbie Greenfield

It is time to challenge the assumption that the famous links courses of the British Isles provide its greatest golfing experience. For sheer enjoyment, architectural brilliance and a captivating setting, the heathland classics offer an alternative adventure that will seduce you on sight and leave you craving more

[divider] [/divider]

he great Bobby Jones was right. When you spend a day at Sunningdale Golf Club, it’s extremely difficult to leave the place. “I liked [the Old course] so much I wished I could carry it around with me. It suited my game so delightfully,” Jones recalled after carding historic rounds of 66 and 68 in the 1926 Open Championship qualifying that are generally considered to be among the finest ever played.

he great Bobby Jones was right. When you spend a day at Sunningdale Golf Club, it’s extremely difficult to leave the place. “I liked [the Old course] so much I wished I could carry it around with me. It suited my game so delightfully,” Jones recalled after carding historic rounds of 66 and 68 in the 1926 Open Championship qualifying that are generally considered to be among the finest ever played.

If golf is in your blood, you don’t need to be possessed with Jones’ unique genius for playing it to feel the same kind of affection. Today, Sunningdale – host of the 2015 Senior Open Championship and no less than four Women’s British Opens – remains one of golf’s greatest delights.

The mere name itself conjures images of rolling fairways meandering between swathes of heather, clumps of gorse and sandy scrub. Aesthetically, Willie Park Junior’s creation (later updated by the club’s secretary – and arguably the greatest of all the course architects – Harry Colt) has few rivals. Each hole seems to deliver a unique and equally perfect configuration of vivid green turf, wispy golden fescue punctuated by bursts of flowering purple heather, against a backdrop of pine, oak and silver birch.

As with all the truly classic courses, the bunkering flows with the terrain; a concealed scoop in the ground here, a cavernous trap at the base of a natural depression there. Each bunker is immaculately presented and positioned just so.

A panoramic view of the par 4 17th hole (left) and the opening par 5 hole (right) on Sunningdale’s Old course

Sunningdale Old’s brilliant par 4 fifth hole features the first ever manmade water hazard to appear on a golf course

Deep into a round at Sunningdale, you reach a state of such tranquility that only the rarest golfing gems can boast, lost in your own private battle with the course and cut off from the rest of the world by the silent wall of trees on either side. And this magic does not only apply to the celebrated Old course. Colt’s New course is perhaps not quite so charming, but it brings a different set of strategic challenges to a more traditional open heathland setting, making the playing of both courses on the same day an unbeatable combination.

Together, the Old and New courses at Sunningdale comprise the best 36-hole golfing experience in the UK

So good, in fact, that 36 holes don’t seem like enough. As we sat on the clubhouse terrace having played the Old and then the New on a warm, sunny day in mid-July, even the club’s famous afternoon tea couldn’t entirely persuade us that the day’s golfing action was over.

“Do you think they would mind if we snuck out for another nine?” asked my rambunctious American playing partner, Mike, ruminating on a mouthful of scones and jam, before adding: “I’m a heathland guy now. Don’t ever take me to one of your so-called ‘championship’ links courses again.”

Harry Colt’s New course at Sunningdale is more open and traditionally heathland in style than it’s sister course the Old. This is a view from the fairway of the long par 4 12th hole

THE FINEST FORM OF GOLF

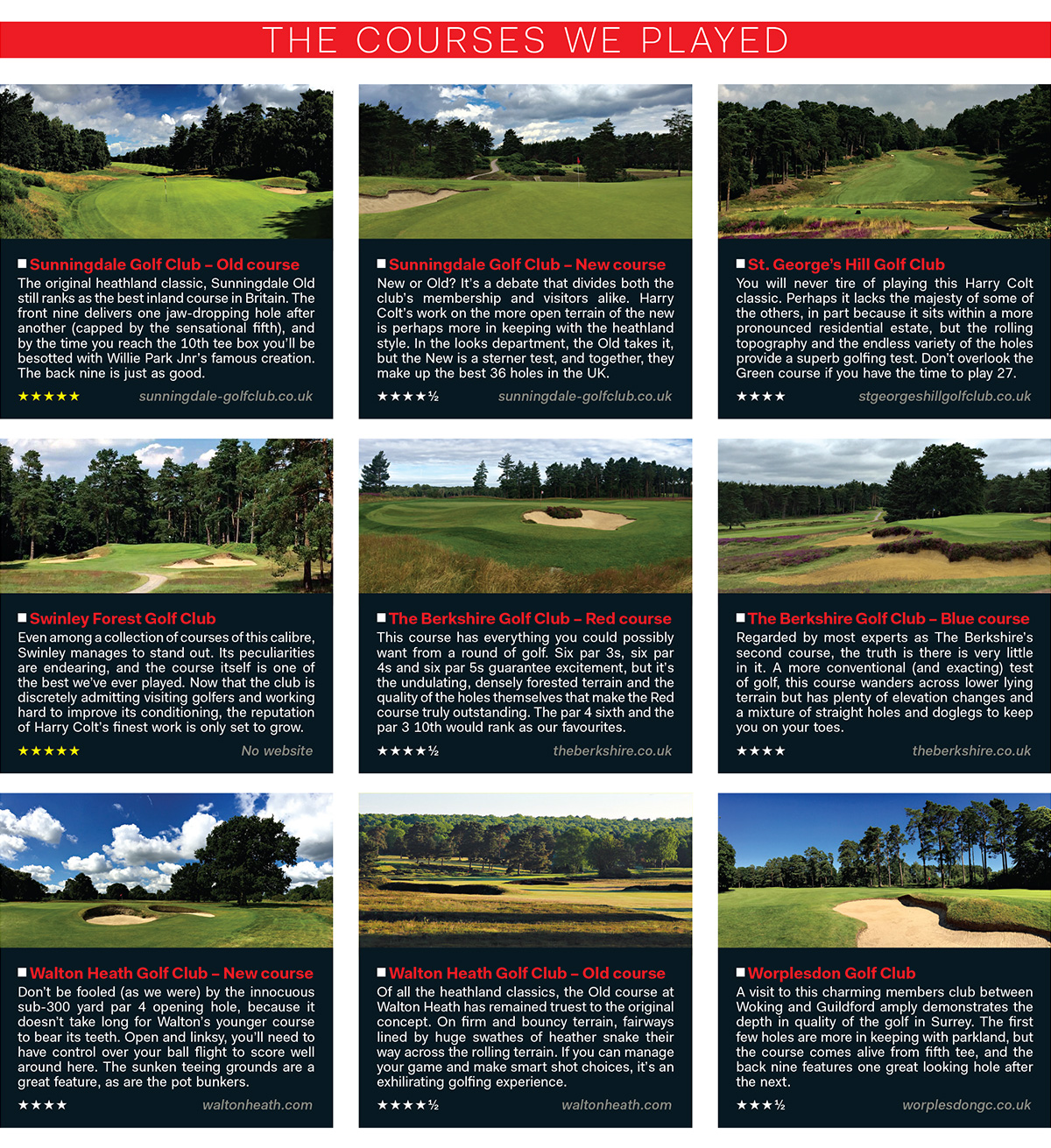

Sunningdale was the headliner on our trip to play the five clubs the recently established Golf Tourism England refers to as the heathland classics, but the truly staggering thing about this collection is their depth in quality. In a combined 108 holes at Sunningdale, The Berkshire Golf Club and Walton Heath, a further 27 at St. George’s Hill and 18 at Swinley Forest Golf Club, you would be hard pressed to pick out a single forgettable shot. We also played Worplesdon Golf Club near Guildford, which provided yet more evidence of the extraordinary volume of great heathland golf in the Surrey-Berkshire area. It was one of those trips where my favourite hole, and even my favourite course, changed on an hourly basis. By the time we reached the magical Swinley Forest (more on that particular gem later) I was ready to join Mike and swear a solemn allegiance only to the courses that possessed this magical combination of springy turf, heather and pine.

The six clubs we visited are all located on the famous Surrey-Berkshire sandbelt to the southwest of London and are within a 25 minute drive of one another

You might wonder why Sunningdale’s famous neighbour Wentworth is not included in the cluster. Well, the West course originally designed by Colt but subsequently transformed by Ernie Els and his design team to cater to the requirements of hosting the European Tour’s BMW PGA Championship, no longer exhibits the hallmarks of a quintessential heathland track.

Contrastingly, the courses we played have remained largely unchanged since they were first laid out by the legendary triumvirate of classic course architects between 1901 and 1928: Park Jr, Colt and Herbert Fowler. Indeed, the proliferation of pine trees at several of these clubs has prompted strategic thinning designed to restore some of the open, rolling vistas on the original layouts.

When you visit any of these five clubs you feel like you are stepping back in time, and I mean that in a good way. The very best parts of the game have been carefully preserved together with a serene ambience, but what was notable on our trip was the total absence of pretentiousness.

The Old course at Walton Heath is the closest thing you will find to an inland links. This is a view of the par 4 fourth

Positioning the heathland classics as a halfway house between parkland and links golf is probably as good a starting point as any, and the experience that most closely resembles the latter is to be found at Walton Heath Golf Club. Founded just two years after Sunningdale in 1903 and featuring two courses designed by Herbert Fowler, famed golf writer Bernard Darwin once said: “If there is something golfers want and do not get at Walton Heath, I do not know what it can be.” Sir Nick Faldo has called this the ‘finest, and most authentic’ of all the heathland courses, and it’s got a history to match.

The courses we played have remained largely unchanged since they were first laid out between 1901 and 1928

Walton Heath hosted the 1981 Ryder Cup (a contest that an American team featuring no less than 11 major champions won by a landslide), and the Senior Open Championship in 2011. Furthermore, it has been the USGA’s choice of international U.S. Open qualifying venue for the past 11 years. Comprising the Old and New courses (New being a relative term – it opened in 1907), 35 of the holes are located on a vast expanse of open land across the road from the clubhouse, practice area, and the first hole of the Old, which happens to be a rather intimidating 235-yard par 3.

The New course at Walton Heath occupies the same expanse of open land as the Old and is a firm, fast course with plenty of heather

It goes without saying that Walton Heath has bundles of charm, prompting Mike to comment on arrival (this time between mouthfuls of bacon roll) that the view across the putting green from the clubhouse patio was ‘impossibly quaint’. Allowing for the fact that being American, Mike tends to describe anything built before 1983 as quaint, he had an inarguable point. Like many old links courses, Walton Heath feels like it has been there forever. The greens flow seamlessly to the next tees just like an old links, and there is an abundance of short par 4s, a type of hole that has been criminally phased out by the modern obsession with 7,000-plus yard courses.

At 286 yards, the first on the New is one such example, and when Mike’s 3-wood scampered onto the green and came to rest 15 feet from the pin, he turned to me with one of those unbearably smug grins that suggested the next few hours in his company would be challenging. He may have also said: “Yeah, baby.”

I needn’t have worried. Walton Heath hosts U.S. Open qualifying for a reason – it is tricky. Two holes later, we were given a sharp reality check when a pair of drives we had been quite happy with were eventually discovered in ankle-deep heather. By the turn, Mike’s smug grin had turned into a perplexed grimace. “I don’t feel like I’m playing badly at all,” he muttered, while tapping in for another double-bogey on the long par 4 12th.

A suggestion for the gents when you play at Walton Heath: don’t do what we did and blindly cling to your ego from one of the longer sets of tees. This exposed, breezy heath can beat you up if you’re just a little wayward off the tee, and this form of the game is too much fun to be played from the heather (which as pretty as it is, is no fun whatsoever).

The brilliant Berkshire Red course features six par 3s, six par 4s and six par 5s in its par 72 layout. This image shows the par 3 fifth green (left) and the dogleg par 4 sixth fairway (right)

While members at The Berkshire and even Sunningdale are often torn between which of their courses is the better, at Walton Heath there is no doubt that the Old is the superior layout. It occupies the more interesting terrain and has a greater variety of holes, together with more unusual quirks.

From one Herbert Fowler classic to another, our next stop was the majestic Berkshire Golf Club near Ascot. Maybe it was the stag emblem on the front gate, or the sight of a member walking up the first accompanied by his dog, but either way we knew instantly that we had arrived at a special, unique club.

Playing the Red and Blue courses at The Berkshire either side of its famous carvery lunch amounts to one of the most enjoyable days of golf you can have in the UK – or anywhere for that matter. Like Sunningdale, the courses compliment one another. Both wander off deep into the heart of a dense pine forest lined with bracken and rhododendron bushes, but the Red course takes you across higher, more undulating ground. Its unusual configuration of six par 3s, six par 4s and six par 5s is a delightful riposte to the standard par 72 layout, and we were soon wondering why more courses hadn’t copied the formula. “Six outside birdie chances in one round?!” exclaimed Mike rapturously. “That’s more than I have in a year.”

The second hole at The Berkshire’s Red course is a short, uphill par 3. Away to the right the par 5 third hole’s fairway plunges downhill

By the exquisite par 3 fifth hole, we were in mutual agreement that the Red course had blown us away. Sliding doglegs, uphill approach shots, fairways that plunged between avenues of pine trees and exhilirating par 3s playing across valleys of heather – this course is an assault on the senses and every hole seemingly announces itself as a candidate for the best one you’ve played yet.

A day playing both courses at The Berkshire convinced us that we had stumbled upon some profound golfing secret

“The Blue cannot live up to that. No way,” asserted Mike at lunch, dividing his attention between this premature course review and a slice of medium-rare roast beef. Well, it did. Ok, I think we’d both pick the Red as a marginal favourite, but it’s mighty close. The Blue opens up with another par 3 and the first few holes are slightly more parkland in style, but we were soon gazing in admiration from every new tee box as the familiar blend of fescue and heather gave way to pulpit greens popping up like islands surrounded by artisitically contoured bunkers.

The par 3 13th – one of my favourite holes on either course – was a great example of this style, with the raised green extending on a platform above a large bunker sporting a full beard of purple heather, and giving way to a steep drop-off to the left. On the rare occasion that we did hit an accurate iron shot, we watched with immense satisfaction as the ball flew above these sensationally picturesque short holes.

The par 3 13th hole on The Berkshire’s Blue course was one of our favourite short holes on the entire trip

It was during our day at The Berkshire when we realised that a trip to play the heathland classics could hold its own against any other golfing itinerary on the planet. We knew Sunningdale was going to be sensational, and Walton Heath’s reputation precedes it. But to visit a club where the golf is this good, and where no one there takes themselves remotely seriously, convinced us that we had stumbled upon some profound secret barely 15 miles from one of the world’s busiest airports.

THE GREATNESS OF HARRY COLT

After playing 72 holes of Fowler’s finest work, it was time to return to our old friend Harry Colt, first to St. George’s Hill and then finally to Swinley Forest. I’ll say this, the man was a genius. It is amazing to think that he designed these courses over a century ago and they are still just as strategic, just as clever and just as downright enjoyable today. From hickory clubs to the very latest titanium composites, manufacturers have poured every last drop of technological know-how into modern club design, and a Harry Colt par 3 still has the ability to make you go weak at the knees.

You could find plenty of avid golfers in Surrey who would argue that St George’s Hill occupies the finest site Colt was given to work his magic on. As the name suggests, the topography here on this opulent estate on the outskirts of Weybridge, is varied and sweeping. Featuring three nines of Red, Blue (which together make the championship 18-hole course) and Green, the first and 10th holes tumble away in opposite directions from the clubhouse, perched imperiously on the top of the hill.

The view from the clubhouse looking up the par 4 first hole at St. George’s Hill Golf Club

St. George’s Hill has the most impressive clubhouse I’ve seen in the UK and I invite anyone to suggest an alternative. It’s a magnificent red-brick building with a terrace that offers panoramic views across the property. As you come up the ninth and 18th holes, the clubhouse, with its giant red and white flag fluttering above, dominates the backdrop.

While I realise this feature is in danger of sounding like a broken record, the golf here is as fun as the holes are pretty. Colt’s legendary eye for a par 3 was as sharp as ever when he went to work here in 1911, because the third, eighth, 11th and 14th holes are all superb. There isn’t a single flat hole on the course, but the only semi-blind tee shots you face all day are at the 10th and 12th par 4s.

Every so often during the round, a giant mansion will loom up from behind the pine trees like some towering Himalayan peak, and these range from the more attractive old English red-brick style houses to hulking continental structures where presumably the oligarchs go to unwind.

Harry Colt is renowned for his par 3s, and the four at St. George’s Hill are all excellent – perhaps topped by the eighth

Having played there several times now I have become a huge fan of St. George’s Hill, from its brilliant layout to its friendly and welcoming members. But on a personal note, my favourite of all has to be our final port of call, Swinley Forest. This beautifully eccentric club right next to The Berkshire was Colt’s own favourite too, a design he modestly referred to as ‘my least-bad course’, which is another way of saying it’s one of the best examples of golf course design on the planet.

Back in the early 20th century, the 17th Earl of Derby commissioned Colt to build the course at Swinley under the strict proviso that lady members would be admitted from the start – the first of so many refreshingly unusual statistics that illuminate the history of the club. The links-like burn that snakes its way across the first and 18th holes had to be moved from its original spot when it was revealed that Lady Derby had trouble carrying it on her opening drive, and so began the culture of a course, and a club, that has dedicated itself to the simple pleasures of the game, with none of the accompanying stuffiness.

Swinley Forest is a stunningly beautiful course which makes use of the tremendous natural green sites – here showing the short par 4 11th hole (foreground) and the par 4 14th holes

For many decades, Swinley Forest existed in its own bubble, detached from the rest of the world. It has always been a highly private club, but until quite recently, the place was shrouded in mystery. Few knew much about it, and even fewer got to play it. But thanks to the progressive attitudes of current secretary George Ritchie, Swinley has opened its doors – albeit to the discerning golfer who wants to pay homage to Colt’s greatest masterpiece.

Ritchie has also worked tirelessly to improve the condition of the course. “It deserves to be recognised as one of the best courses in the world, and with that, it deserves to be in the best possible condition,” he told us during our visit.

A truly outstanding collection of par 3s at Swinley Forest are completed with the 17th hole and its pulpit green

Ritchie knows Swinley will never have the star power of Sunningdale or Walton Heath, but he and everyone at the club are happy in the knowledge that what they have is something unique. “We don’t take many new members because those that join stay here for life,” he told us. “Once you become a member here, it’s very difficult to go somewhere else and experience something better.” It was said so matter-of-factly, but he’s right. The members at Swinley don’t carry handicaps and they don’t hold competitions. Ever. Such administrative affairs merely interrupt the joy of just playing.

And what a joy this course is. If Colt is known for his par 3s (among many other things), it’s here that he discovered the greatest collection – and such is their quality that he identified the sites for the five short holes first, before building the rest of the layout around them. I haven’t been lucky enough to play New Jersey’s Pine Valley (another course in which Colt had a considerable hand) but if it really does have a better bunch of short holes than Swinley, I truly hope I one day get to see them.

A view looking back down the par 3 fourth hole at Swinley Forest, with the par 5 fifth fairway in the background

When you stand on the tee of the fourth, you will ask yourself if you’ve ever played a better looking par 3. You’ll be posing the same question on the 10th. The 17th caps an outrageous collection of one-shotters with a hole that must surely have inspired A.W. Tillinghast’s effort on the 10th at Winged Foot West. A pulpit green dares you to hit an accurate shot in the full knowledge that left or right is likely to result in bogey being a good score.

Elsewhere, the layout’s endless sequence of majestic pars 4s and its two par 5s frequently cause you to lose focus and just stand there, gazing awestruck at nothing in particular. I did that on the fifth, seventh and ninth tee boxes alone, to say nothing of the occasional fleeting glimpse of other holes you’ve yet to reach, stretching out beyond a row of pines towards yet another perfectly formed crowned green.

In his playing days, Harry Colt used to talk about ‘a craving for my usual game around the Swinley Forest course’. Craving. It’s an apt word for Swinley, and it’s an apt word for the heathland classics in general. Colt’s affection for his favourite course was no different from Bobby Jones’ wish to carry Sunningdale back home with him. These two great courses, together with the others on this trip, are about more than just a rewarding golfing experience. As Mike will happily testify, once you’re bitten by the heathland bug, one visit is nowhere near enough. We’ve already started scouring dates for 2017.

[divider] [/divider]

![GTE-Logo[1]](https://golfdigestme.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/GTE-Logo1-150x150.jpg) Special thanks to Golf Tourism England and the featured golf clubs

Special thanks to Golf Tourism England and the featured golf clubs

Golf Tourism England has set out to put England’s incredible golfing offering on the map for visiting golfers from around the world, grouping clusters of great courses together. For more information on golf in Surrey and Berkshire, email: [email protected]

or visit golftourismengland.com