By John Huggan

Almost without interruption, it’s been going and growing for more than six decades. These days, it is a $7 million tournament held annually on one of Britain’s most famous courses. And in normal times what is now the BMW PGA Championship at Wentworth boasts a strength of field commensurate with that elite status. But what will be presented to the world this week as the European Tour’s “flagship” event hasn’t always been such. Truth be told, it took a while for what is now the most significant event on the Old World circuit to make the transition from humble to hallowed.

Early progress was slow to the point of immobility in the years after its first playing in 1955, when six-time Ryder Cupper Ken Bousfield won at Pannal Golf Club in Yorkshire, thanks to the fact many outside the British Isles weren’t even remotely aware the event existed. Between 1955 and 1966, participation was limited to English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish members of the game’s oldest professional golfers association. Why then would anyone else pay attention?

Which is not say that the origin of the event did not have at least one powerful and influential backer. Three-time Open champion Sir Henry Cotton was, according to veteran television commentator and eight-time Ryder Cup player Peter Alliss, a “driving force” behind the early PGA Championships.

“Henry felt strongly that there should be a PGA Championship,” says Alliss, who would win the event three times, a record until Nick Faldo’s fourth victory in 1989. “He saw it as affording British professionals a certain status in the world of golf. That was important because it was so difficult for us to go and play in America. Things were different then. I never thought I would see the day when so many of our leading players would live in the States. In my day, that was never going to happen because they made it so difficult for us to go over. We weren’t wanted there, especially if you could really play.”

That same sort of insularity had to change if the new tournament was to make progress. And it did, albeit only after a false start. The first response to criticism of the obviously restrictive entry requirements was the staging of “open” and “closed” versions of the tournament in 1967 and ’68. In other words, any professional from anywhere in the world could participate in the “open” event.” The “closed” version remained available only to those hailing from GB&I.

That attempt at compromise, however, didn’t work so well. By 1970, the championship had fallen into what turned out to be brief abeyance.

“The early 1970s was a turbulent period for the [British] PGA as an organization,” explains Alliss, who has twice served as the organization’s captain. “There was a lot going on, a lot of changes in management at the top over a short period of time. So there was a lot of negativity until the European Tour came into being. That changed everything, of course.”

The “Viyella” PGA Championship, a smaller-scale forerunner to today’s big-time reality, returned in 1972 (at Wentworth) as part of that newly-formed European Tour. (The British PGA did retain an interest in the event, as it still does, in that a small minority of the field qualify to play through PGA regional tournaments). Subsequently, six more sponsors have inserted their names ahead of “PGA.” And five other courses played host (Royal St. George’s, Royal Birkdale, The Old Course at St. Andrews, Ganton and Hillside) prior to Wentworth’s West course, the “Burma Road,” making its second and so-far permanent comeback in 1984.

“We always had a good venue and good sponsors,” says Ken Schofield, whose 29-year tenure as European Tour executive director ended in 2004. “But I can’t claim we had any kind of long-term plan in place. As was the case with a lot of things back then, it was intuitive.”

In retrospect, the 1975 championship at a blustery Royal St. George’s was especially significant. Arnold Palmer, 45, came from far behind with one of his patented charges (his final-round 71 was at least seven strokes lower than anyone in the top 10 after 54 holes) and won the £10,000 first prize in what was by then the Penfold PGA Championship. Just as his mere presence had done for the Open Championship 15 years earlier, golf’s most-charismatic performer raised the profile of the tournament to a previously unimagined height.

“It was the biggest event on the European Tour by then, bigger than any national Open. And we all wanted to play in it,” recalls swing coach Denis Pugh, who works with former Open champion Francesco Molinari and played in the event in 1975 at St. George’s. “But it was a bigger deal that year because Arnold was there, although it had nothing like the prestige it has now. I recall watching him walk down a fairway wearing a cashmere sweater. On a day when the rest of us needed four layers just to feel cold. He was the ultimate macho-man.”

Even as the tournament continued to grow in stature, a caveat hovered just beneath the surface. And it lingers today. Maybe because the European Tour has necessarily or unintentionally (take your pick) diminished the resonance of the title through the prominent presence of so many commercial entities, the PGA of America has, rather presumptuously, assumed ownership of the phrase “PGA Championship.”

It may seem pedantic, but “USPGA Championship” is a more accurate and appropriate title for the major held each year in the U.S. The PGA in Britain, the world’s first association of golf professionals, was born in 1901, 15 years ahead of the American version. And with age and precedence comes rank and privilege.

“The Americans understand marketing,” says a smiling George O’Grady, European Tour chief executive between 2005 and 2015. “I once had a chat with [former PGA Tour commissioner] Tim Finchem. I told him there really should be two brands for the entire world. ‘The PGA’ for the club professionals around the world. And ‘PGA Tour’ for all the professional golfers, which would make his organization the ‘U.S. PGA Tour.’ He was quick to dismiss that notion.”

Still, despite the New World’s indifference, the early days of the Old World PGA Championship were not totally lacking in merit. Not in Alliss’ mind at least.

“It quickly became a little bit more than an ordinary tournament,” says Alliss, 89. “If you won, you were a champion, the best in Britain. So it had quite a bit of kudos. Having said that, we were playing at far more modest venues and for a lot less money. First prize was something like £400, which was a lot then I suppose. So it had some razzamatazz to it. And it was certainly an event I enjoyed winning. It was just a little bit above the rest.”

It was also an innovator. At least in one respect, the championship was moving with the times. At Dunbar in 1968, the then Schweppes PGA Championship became the first “big-ball” tournament in Europe. Englishman David Talbot’s eight-under-par winning score over the East Lothian links was achieved with the 1.68-inch diameter ball, rather than the 1.62 version.

Into the 1970s, the prestige of the event was soon accelerating, as evidenced by the list of winners. BP (before Palmer), former Open and U.S. Open champion Tony Jacklin won in 1972. And 12 months later, then European No. 1 Peter Oosterhuis succeeded his biggest rival.

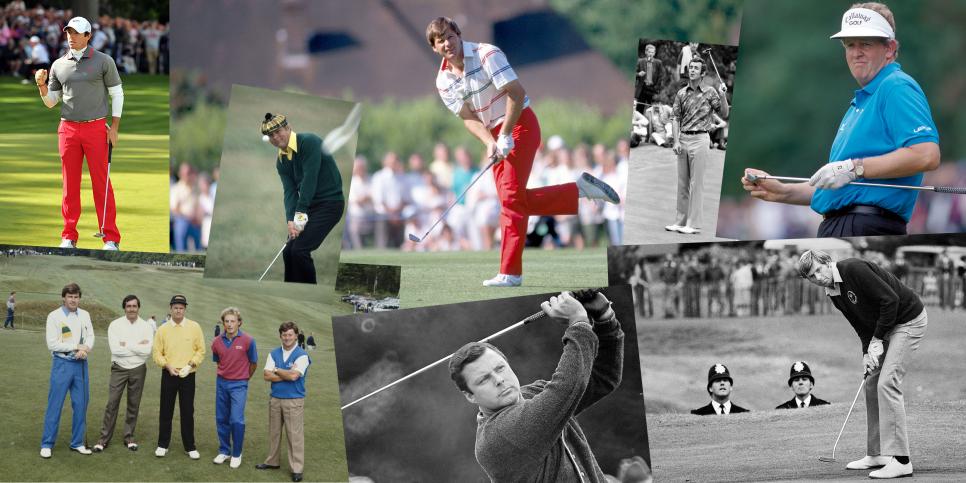

Even more significantly, by the end of that decade the so-called “Big Five” of European golf—Faldo, Seve Ballesteros, Sandy Lyle, Ian Woosnam and Bernhard Langer—were emerging and blossoming en route to accumulating 16 major victories between them. Only Lyle would not win the PGA Championship at Wentworth, although the Scot came close, losing a playoff to Paul Way in 1985. Throw in Jose Maria Olazabal, Colin Montgomerie, Angel Cabrera, former World No. 1 Luke Donald, Rory McIlroy and Molinari and the tournament today boasts a fittingly stellar list of past champions.

“The buy-in from the top five was crucial,” O’Grady says. “The key to what the PGA Championship has become today was the support of the leading players in the 1980s. Faldo in particular was a huge boost to the prestige of the event. For whatever reason, he saw it as a big deal. Back then, I was managing director of Tour Enterprises, but I was also, in effect, the tournament director. My job was to negotiate with the players as well as run the commercial side of the operation.”

Peter Dazeley

The exceptional record in the tournament from Europe’s Big Five of Nick Faldo (four wins), Seve Ballesteros (2), Sandy Lyle (playoff loss), Bernhard Langer (3) and Ian Woosnam (2) helped cement the event as the biggest outside the majors on the European Tour.

The burgeoning success O’Grady describes wasn’t all about the willingness of star players to show up, albeit they were and are an obvious prerequisite for any aspirational tournament. Another big plus was extensive BBC TV coverage, the viewing figures enhanced by the event finishing on Monday, the May Bank Holiday in the U.K. Throw in the annual World Match Play Championship that ran from 1964 to 2007 at Wentworth and a special connection was thus created between fans and venue. Reminiscent of the relationship that exists between golf fans and Augusta National, Wentworth’s holes are today familiar to millions who will never see the course in person. All in all, the end result represented a potent package, one only enhanced by a shift to September when the now twice re-designed lay-out is typically in better shape.

“It’s a title we all grow up craving to win, more than any other on the European Tour,” says former Ryder Cup captain Paul McGinley, neatly summing up the prevailing view.

Further adding to the mix is the unpredictability of the eventual result. Not every champion at Wentworth has been a bonafide superstar. Journeymen have popped up now and then. Simon Khan. Scott Drummond. Andrew Oldcorn. Anders Hansen (twice). Chris Wood. Tony Johnstone. All have lifted the trophy. And for all, victory was life-changing.

“The PGA Championship was a huge event by the time I won it,” says Johnstone, who outdueled Faldo on the final day in 1992. “That the top guys all played throughout the 1980s was huge in terms of establishing the credentials of the event. The big thing for me though was the 10-year [tour] exemption [now reduced to three] that came with the £100,000 winner’s check. That meant I could have a bad year, or an injury and still have my card the following season. I did keep my card every year without the exemption, but that was at least partly because I knew i had that safety net. I was able to just go out and play, which was a massive relief mentally.”

Andrew Redington

Having the likes of Rory McIlroy in 2014 (shown), Francesco Molinari in 2018 and Danny Willett in 2019 win the title helps connect the tournament to the current generation of European Tour stars.

Through all of the above one thing has been noticeably missing: anything more than sporadic American participation. But even that was showing signs of change. In 2019, Billy Horschel, Patrick Reed, Kurt Kitayama, Andrew Putnam, Julian Suri, Tony Finau and David Lipsky made up a record seven-strong contingent. This year, however, has a different look. Of those seven Americans, only Reed, Kitayama and Suri are returning. Like the European Tour on which it stars, the BMW PGA is, in many ways, poorly positioned to cope with the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic.

It remains to be seen, for example, how many of the U.S.-based European stars will cross the Atlantic to play at Wentworth in years to come. McIlroy, Jon Rahm, Paul Casey, Luke Donald, Viktor Hovland and Henrik Stenson aren’t flying over this year. The most recent European winner on the PGA Tour, Sergio Garcia, citing tax issues, never more than an occasional visitor, is another absentee. The six events on the so-called U.K. Swing earlier this year featured fields well below the norm. Top 50 players were hard to find. The fear is that, even boasting an exceptional purse, the BMW PGA Championship will suffer a similar fate.

“We’ll get through it though,” insists McGinley, who serves on the European Tour’s board of directors. “It’s just a question of what is left at the end of it. How swiftly can we come back? We’re dealing with some really difficult curveballs. The restrictions imposed by the British government are so severe. We have to deal with international players. And we have to deal with the travel that comes with being a truly international tour. So we have a number of headwinds against us.”

McGinley’s ultimate optimism is likely justified. In the 65 years that have passed since its low-key inception, the Schweppes/Viyella/Penfold/Colgate/Sun Alliance/Whyte & Mackay/Volvo/BMW PGA Championship has always found ways to survive and thrive.