In an adaptation from a new book, how one of golf’s most mystical figures straddled the line between art and science

By Brett Cyrgalis

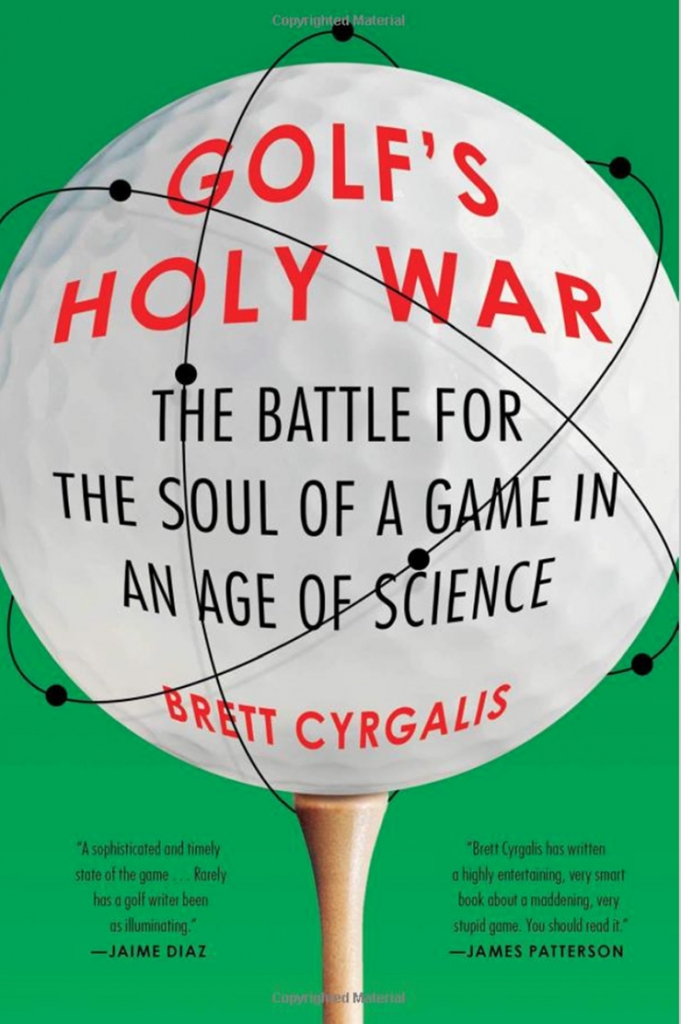

This essay was adapted from Brett Cyrgalis’ book, “Golf’s Holy War: The Battle for the Soul of a Game in an Age of Science” (Avid Reader Press, May 2020). It’s available for purchase here.. You can also listen to a podcast conversation with the author below.

The story goes that Ben Hogan had a “secret.”

In 1953, Hogan agreed to be interviewed for an article in a three-year-old magazine called Golf Digest. This was his first telling of the “secret,” a twenty-minute practice routine he did every morning.

“With his feet close together, the Little Man clamps his arms tight against his stomach [and] starts a short swing of a few inches, arms still close,” wrote the author, Lawrence Robinson. “Then he gradually lengthens the backswing a foot at a time. He does this for twenty minutes each day until he is taking a full swing, all the while from the close-to-the-body position.”

From there, the “secrets” kept coming. In 1954, Hogan accepted $10,000 from Time magazine for a story titled “Ben Hogan’s Secret: A Debate.” Seven pros in the story guessed what it was, with Sam Snead saying, “Anybody can say he’s got a secret if he won’t tell what it is.” On August 8, 1955, Life ran the revelatory follow-up “Hogan’s Secret.” In that article, Hogan told an apocryphal tale about having an enlightening dream in 1946—the year he won his first major—in which the old Scottish term pronation came to his mind. Pronation meant that he cupped his left wrist at the top of the swing, making it almost impossible to hit a hook. Combined with a weakened left-hand grip and a “fanning” of the club open on the backswing, there was Hogan’s “secret.”

Really, it was a good way to describe to someone how to slice it.

Jimmy Ballard, named “Teacher of the Decade” in the 1980s, said he had a letter Hogan wrote to his personal doctor sometime in the 1950s. Ballard said the doctor had come to him for lessons and they made a copy under the strict stipulation that Ballard not share it. In the letter, Hogan had drawn some stick figures, explaining in his swirling and large cursive what he called “a new feel in my golf swing.” The language was candid—referring to his testicle as his “nut”—and Ballard felt it verified his own teaching methodology.

“At the top of the back swing the groin muscle on the inside of your rt [sic] leg near your right nut will tighten,” Hogan wrote. “This subtle feeling of tightness there tells you that you have made the correct move back from the ball.”

Decades later, that student, Dr. William P. Huckin, was a semi-retired dentist. While he was a student at SMU in the 1970s, he met Hogan twice. Hogan would be out on the eleventh fairway at Shady Oaks almost every day at 1:10 p.m., hitting balls to a stationary caddie. Huckin had gotten his hands on a four-page document that Hogan used to give his private students—students!—at nearby Preston Trail Country Club. Huckin asked Hogan about the stick figures and the lessons, and Hogan confirmed it all.

“I didn’t fully understand or appreciate what he was saying,” Huckin said. “I really didn’t.”

There were many more similar tales, with a Louisiana teaching pro named Larry Miller explaining how he got a letter from Tommy Bolt, whose PGA Tour career was saved with some advice in a letter from Hogan. Al Barkow, a golf historian, also had a story about a letter, one going back to touring pro Loren Roberts, who claimed he had a thirteen-page document that Hogan had written to the head pro at Pasatimepto Golf Club, Pat Mahoney.

“To verify a correct backswing,” Hogan wrote, “at the top of the backswing the groin muscle on the inside of your right leg near your right nut will tighten. This subtle feel of tightness there tells you that you [can make] the correct move back to the ball.”

Barkow also heard Hogan speak firsthand about his “secret.” When the PGA Tour started its minor-league affiliate, its title sponsor was Hogan’s company. Before the launch of that Tour, Barkow was granted a long sit-down interview with Hogan, during which Hogan said that the real “secret” would be revealed. After much talk over lunch, the two were walking down a hall at Shady Oaks, and Barkow asked Hogan for the secret. Hogan pulled him inside the kitchen so no one else could hear. He told Barkow to set up as if he were going to hit a shot. Then Hogan told him to move his head to the right.

That was it. That was the secret. Moving his head to the right. Barlow asked if it was a gimmick, a trick, a joke—and Hogan swore it wasn’t. He said the tip went back to Bobby Jones.

So why, for the following half-century and into today, did teachers use Hogan as an example? Why did so many people scour the archives looking for ancient video of his swing, hoping to glean the smallest bit of insight into what made him great? Why could no one accept that maybe the answer wasn’t a piece of technical information?

Because there was always something more to Hogan, something that attracted people more than just the technicality, the Lazarus-like recovery from his car accident, or that mysterious “secret.” Shortly before Bobby Jones died in 1971, he was asked which great player he would select if he needed to win a major tournament.

“That’s not hard for me to answer: Hogan,” Jones said. “He had the intangible assets—the spiritual.”