By Daniel Rapaport

Editor’s Note: This cover story appeared in a recent issue of Golf Digest Middle East, before Collin Morikawa won the 2021 Open Championship.

No two golfing journeys are identical. But if there is a common theme, it’s turbulence. Golf drags you on a rollercoaster ride—you fall in love with the game and then fall out of it. You make a breakthrough and then hit a wall. The exhilarating successes are sandwiched by humbling failures.

This is true even for the best players in the world. Of course, their ebbs and flows are on a different scale, and their general trajectory is upward. Still, even the superstars have had their struggles. Brooks Koepka wasn’t good enough to get a scholarship offer from his beloved Florida Gators. Phil Mickelson couldn’t get over the major-championship hump until he was 33. Jordan Spieth stormed onto the scene a conquering hero and then dropped out of the top 75 in the World Golf Ranking.

That’s what makes Collin Morikawa’s rise so remarkable—the linearity of it all. It’s uninterrupted. There is, simply put, a whole lot of good and shockingly little bad: a comfortable upbringing in Southern California, an outstanding junior golf career that gave him his choice of colleges, a world No. 1 amateur ranking, a degree from one of the best undergraduate business schools in the world, a tour card less than two months after turning pro, an enriching relationship with a beautiful woman, three PGA Tour victories, millions of dollars, a major championship—all before his 24th birthday.

Morikawa will tell you he is anything but satisfied. That despite how it might appear, he does not have everything figured out. There is, however, ample evidence to the contrary.

‘I’VE BEEN VERY LUCKY’

Debbie and Blaine Morikawa co-own a commercial laundry business near downtown Los Angeles that delivers linens, tablecloths and the like to restaurants throughout L.A. It has been in the family for quite a while. Nothing crazy lucrative, but more than enough to provide Collin and his younger brother, Garrett, who is 17 and prefers soccer over golf, a worry-free childhood in La Cañada Flintridge, a small upscale enclave just north of Pasadena.

“I’ve been very lucky,” says Collin, who now lives in Las Vegas—on his own but not too far away from home. He misses L.A., of course, but “you know, taxes.” He thinks about money these days, in the good way—because he has a lot of it. He didn’t when he was younger.

“We never had to think about money growing up,” he says, “never had to think about what we were having for dinner. I wasn’t a kid that wanted many things; I never asked for a lot. But if I did need something or I did want something, I was very lucky to have parents who were able to afford stuff like that.”

His family traveled frequently, often to Hawaii, where his fraternal grandparents still live and where he attributes his love affair with the ocean. They would go skiing. They had a membership to Chevy Chase Country Club, a private nine-hole layout in nearby Glendale. But it was at a public course where young Collin’s golf talent began to shine: Scholl Canyon, a 3,039-yard, par-60 track where an instructor named Rick Sessinghaus worked.

When Morikawa was 5, his parents convinced the organizers of a junior golf camp at Scholl to let their son participate. He wasn’t technically old enough, but the bones of his remarkably repeatable golf swing were already in place.

“Rick was the guy at the end of the range who taught the better players,” Morikawa says. “He was the end goal, the guy you wanted as a coach. So after I went through the camp, slowly getting more interested in the game, my parents could see I was getting better. So they approached Rick to see if he would coach me, and by the time I was 8, we had started this relationship.”

That relationship continues to this day. Sessinghaus isn’t your typical swing guru with a stable of professional players. Morikawa is his only student on the PGA Tour, so Sessinghaus has no need to hide his rooting interest. In other words, he cheers. Loudly. And during the fan-less reality of pandemic golf in 2020, he was often the only one. “We fist-bump for birdies,” Sessinghaus says with a smile. We refers to anyone near him, including this writer, who can confirm the policy. “For eagles, I might knock your hand off,” he says.

Of course, Sessinghaus knows the golf swing—particularly Collin’s, which he has molded for 15-plus years. But Sessinghaus also owns a doctorate in applied sports psychology and penned a book called Golf: The Ultimate Mind Game. Not surprisingly, he preaches a holistic method for improvement—he and Morikawa talk often about a “growth mind-set”—and speaks about his relationship with his star pupil as a father gushes about his son.

Their work has never been the typical instructor-stands-behind-the-player-on-the-practice-tee situation. Instead of having a young Morikawa mindlessly hit balls on the driving range, Sessinghaus preferred to simulate situations on the golf course.

“We’d drop balls around the course, and I’d have him play three types of shots,” Sessinghaus says. “On the first, I’d let him do his thing. Then we’d talk about why he chose that shot, what he was trying to do, and he’d make his own adjustments for No. 2. Then I’d give him some technical advice on how to play the correct shot for the situation, and he’d try that shot for the third.”

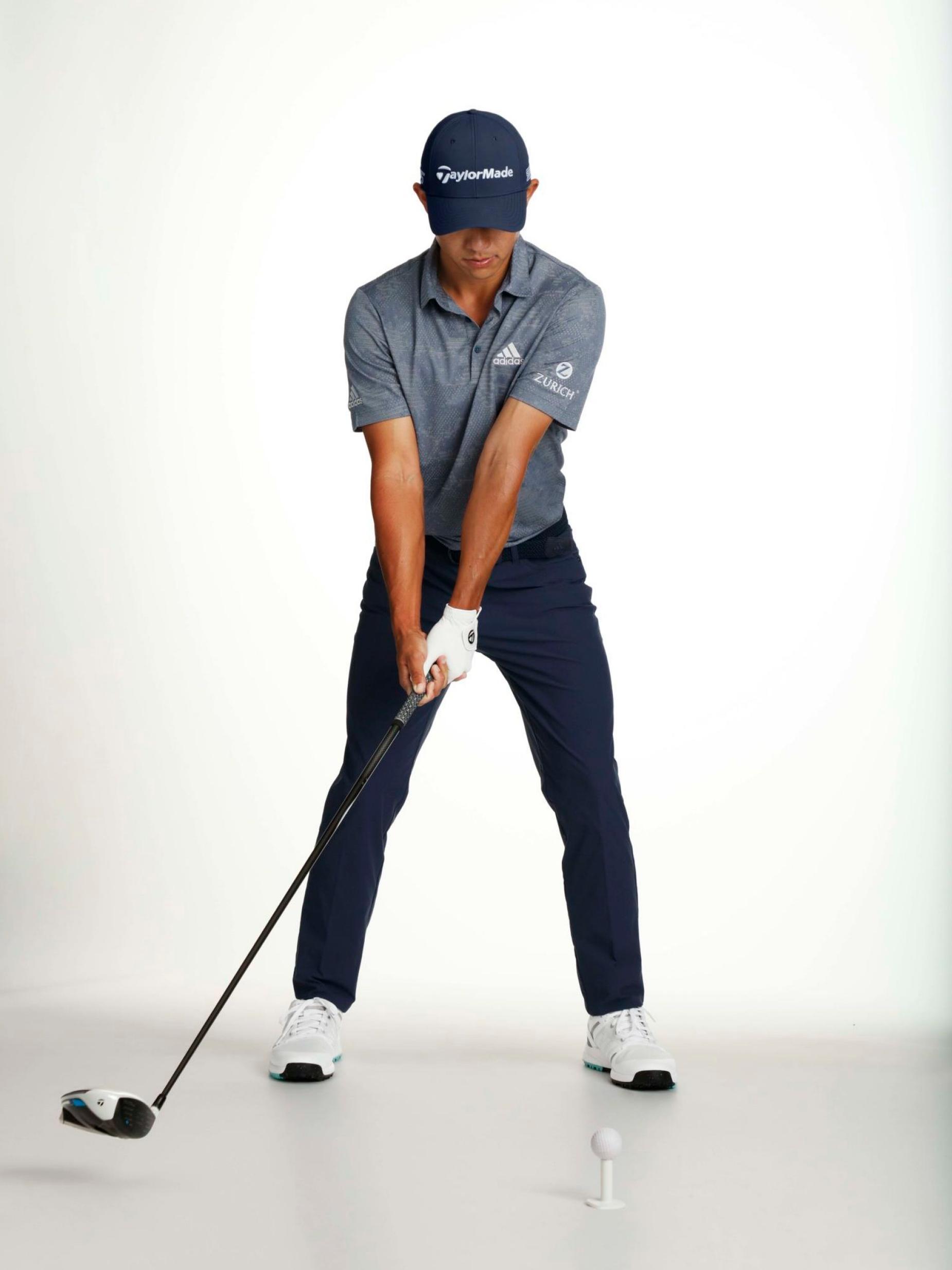

Sessinghaus’ goal has never changed: He wants Collin to be a player, not a hitter, to think about variables and understand his mistakes. Was that a bad swing or a bad decision? Both coach and student credit this philosophy with helping make Morikawa the measured player he is today. You won’t catch Morikawa posting launch-monitor readings to Instagram, and he doesn’t so much rely on adjusted yardages as he does on feel, artistry and athleticism. What Sessinghaus and Morikawa work on has remained consistent since Morikawa was a child: low-tech drills such as hitting flat-footed punch shots and simple methods like varying how high the hands finish to determine shot shape.

Morikawa progressed rapidly. He quit playing other sports around age 10. Baseball was the hardest goodbye. “It’s not like I didn’t want to play other sports,” he says. “I just felt like if I wanted to do this, this is what I had to do.” Eye-popping self-knowledge for a pre-teen. “It was my decision, as a little kid,” he says. “It’s crazy to think about it, but it’s what I loved.”

During the next few years, Sessinghaus grew increasingly certain he had something special.

“I remember this conversation with my wife when I came home after a day working with Collin,” he says. “I told her, ‘He has it. He has that special thing. He’s going to be a professional.’ He was 12 years old at the time.”

A FATEFUL DECISION IN COLLEGE

When it came time to choose a college, Morikawa had options. An accomplished junior with a sparkling report card, he was every college coach’s dream. “I was able to really look at the entire country and say, OK, this is where I want to go,” he says. “My mom went to USC, so I grew up a Trojan fan. The Pac-12 was always in my blood. I always viewed the Pac-12 as the best.”

In the end, he narrowed his options to four California schools: Stanford, UCLA, USC and Cal-Berkeley. He chose Berkeley and wasted little time establishing himself as the alpha of the program, finishing as Cal’s top player in seven of his 14 events as a freshman in 2015-’16. But he didn’t win a tournament that season, and not until that summer did he truly emerge as one of the best players in the country.

In June 2016 he won the prestigious Sunnehanna Amateur with a final-round 62. The next week he teed it up in the Capital Classic, a tournament on what is now the Korn Ferry Tour, which he qualified for by winning the Trans-Mississippi Amateur the year before. It was his first time playing in a professional tournament, so he felt perfectly content to make the cut on the number. Then he closed with two sizzling 63s and drained a 27-footer for birdie on the 72nd hole to get into a three-way playoff.

Ollie Schniederjans ended up winning, but from the outside, it seemed Morikawa had a difficult choice to make: Stay in school or turn pro. Clearly, his game was ready. But he knew he wasn’t prepared at 19 for the solitary life of a professional golfer.

“I don’t think I would have turned pro, even if I won,” he says. “I definitely would have brought it up to my parents, and I would have thought about it. Yes, maybe my golf game was ready, but I wasn’t ready to live that life by myself. People have said I’ve been very mature and, yes, I probably could have lived on my own. But I didn’t go to a school like Cal to play one year, have some good results and leave. Just wasn’t my mind-set.”

Eric Mina was an assistant during Morikawa’s last three years at Cal and remembers meeting him at the first team practice of Morikawa’s sophomore year at Blackhawk Country Club. Mina had been an All-American at Cal and did the mini-tour grind for a few years before returning to the program. He knew what a professional golfer looked like—an awful lot like a teenage Collin Morikawa.

“What caught my eye was his ability to maneuver the golf ball, to really control it,” Mina says. “Whether it was a half shot or a full shot, he knew his yardages. He really knew them. You don’t see that with a lot of pro golfers, so for a 19-year-old kid to have that—extremely impressive.”

Now, there’s staying in school and then there’s staying in school. It’s not exactly a secret that the best college athletes often pick—how should we say this?—manageable majors and classes. If they don’t leave early, as Tiger Woods, Justin Thomas and Jordan Spieth did, then the goal is to stay academically eligible without racking up a particularly stressful workload.

Morikawa missed the memo. During the fall of his sophomore year, just as his golf had begun to take off, he applied to the Haas Business School, the No. 3 undergraduate business program in America, according to U.S. News & World Report. He received his acceptance letter while at a golf tournament in Hawaii, naturally.

“I think the biggest thing that helped us out as far as keeping him in school,” Mina says, “was him getting into Haas. If he didn’t get in, it might have been appealing for him to leave.”

But what use does a professional golfer have for a business degree?

“A bunch of people are coming out of Haas and running their own startups or going into a large business or company,” Morikawa says. “They’re getting great jobs. Me, I’m getting a great job and running my own brand, running who I am as a golfer. I might not necessarily be doing everything, but I understand everything that’s going on.

“I don’t know that everyone out there on the PGA Tour really has a full understanding of everything that’s going on behind them. I’m very aware of that, of what’s going on in the background. Other people, they couldn’t care less. They just want someone to do it for them. But I want to be involved; I want to learn about it.”

Also during his sophomore year Morikawa met Katherine Zhu, a player on the Pepperdine women’s golf team. Morikawa and Zhu shared a mutual friend on the Cal women’s team, and their story of coming together is distinctly modern: The friend showed Morikawa pictures on Zhu’s Instagram page. Morikawa liked what he saw, and the two began texting, eventually meeting over spring break. They have been together since.

“She’s helped me so much,” Morikawa says, quick to point out that he didn’t begin winning tournaments in bunches until she came into his life. “Especially out on tour, it’s a very lonely life. Everyone will tell you, at parts of their career, they’ve been lonely. Having her travel with me, we’ve been able to explore new cities, have good dinners. I’ve just been able to relax, not to stress about the next day so much. I think that’s how some of the best players out there that have families, kids traveling with them are able to flip the switch. On the golf course, it’s golf; it’s business. Off the course, they don’t tire themselves out. Without her, I’d be so focused on golf 24-7, getting antsy about the next round, stuff like that. You can never do that.”

He got into business school, he got the girl, then he started winning. During his last three years at Cal, he won five times and lost in a playoff twice. His junior year, he set a new NCAA scoring record with an average of 68.68 and finished the year as the No. 1 player in the nation. As a senior, he won the Pac-12 individual title and had 11 top 10s in 12 starts.

But perhaps his most impressive feat in college, the true harbinger of his rapid success as a professional, did not come in a tournament at all. It came on a practice range. While he was at Cal, he took a dispersion test on a launch monitor. “They said my shot dispersion with a 6-iron was about the same as the average tour pro’s with a pitching wedge,” he told Golf Digest in 2019. “I guess that’s a humble brag.”