By Derek Duncan

For golfers, April is a trigger. It conjures visions of pink blooming azaleas, white dogwood blossoms, blue-mirrored water and wild sculptures of slick green grass. April, in other words, is Augusta National.

If this is the vision of Augusta National we share now, it’s important to note it wasn’t always quite this way. The course, since it was created, has been in a state of perpetual flux.

When we have the chance to look at photos of the original holes Alister Mackenzie built in the early 1930s, it’s easy to be shocked at how different it was from the current Augusta National. More subtle but no less important are the alterations it made since the 1950s, when the course, and the Masters Tournament, became closer to what we now know them to be.

In the 1930s, a turf researcher named O.J. Noer began travelling widely, taking photographs primarily of experimental grass plots and fertilizer application reactions, but also of golf courses. The following slides of Augusta National were taken by Noer during Masters Week, 1955.

Not much has changed on the par-4 first, except the fairway bunker that has continually shifted further down the fairway.

Note: All photos are courtesy of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District and Michigan State University Turfgrass Information Center

The placement and orientation of the course’s fairway bunkers, as a reaction to improvements in technology and to where the players were driving the ball, mark some of the most notable changes through the years (in preparation for the 2019 Masters, for instance, the bunkers on the inside corner of the fifth hole were deepened and pushed farther down the fairway).

The driving bunker at the par-5 2nd used to be in the centre of the fairway.

The fairway bunker on the par-5 second hole, as seen above, was originally placed in the centre of the fairway to force decisions off the tee. Over the years it has gradually shifted to the right, and now is more of an aiming point for today’s players, a target to work the ball off of.

The par-5 second green in 1955, with the seventh and 17th greens beyond.

The second-most notable difference, and no less critical, is how drastically the bunker profiles have changed. The course’s brilliant white flashed sand faces didn’t exist in 1955. What we have come to identify as a bunker style intrinsic to the Augusta National character came about gradually, originating from flatter floors and thick sod toplines.

The current seventh hole, which today features some of the most obvious and extravagant bunkering on the course, was far less emphatic in Sam Snead’s day (this green was created by Perry Maxwell in the late 1930s—the original seventh as envisioned by Mackenzie had no bunkers).

A more sedated version of the par-4 seventh.

The par-3 sixth looks much the same today, minus the pond, which was removed in 1959.

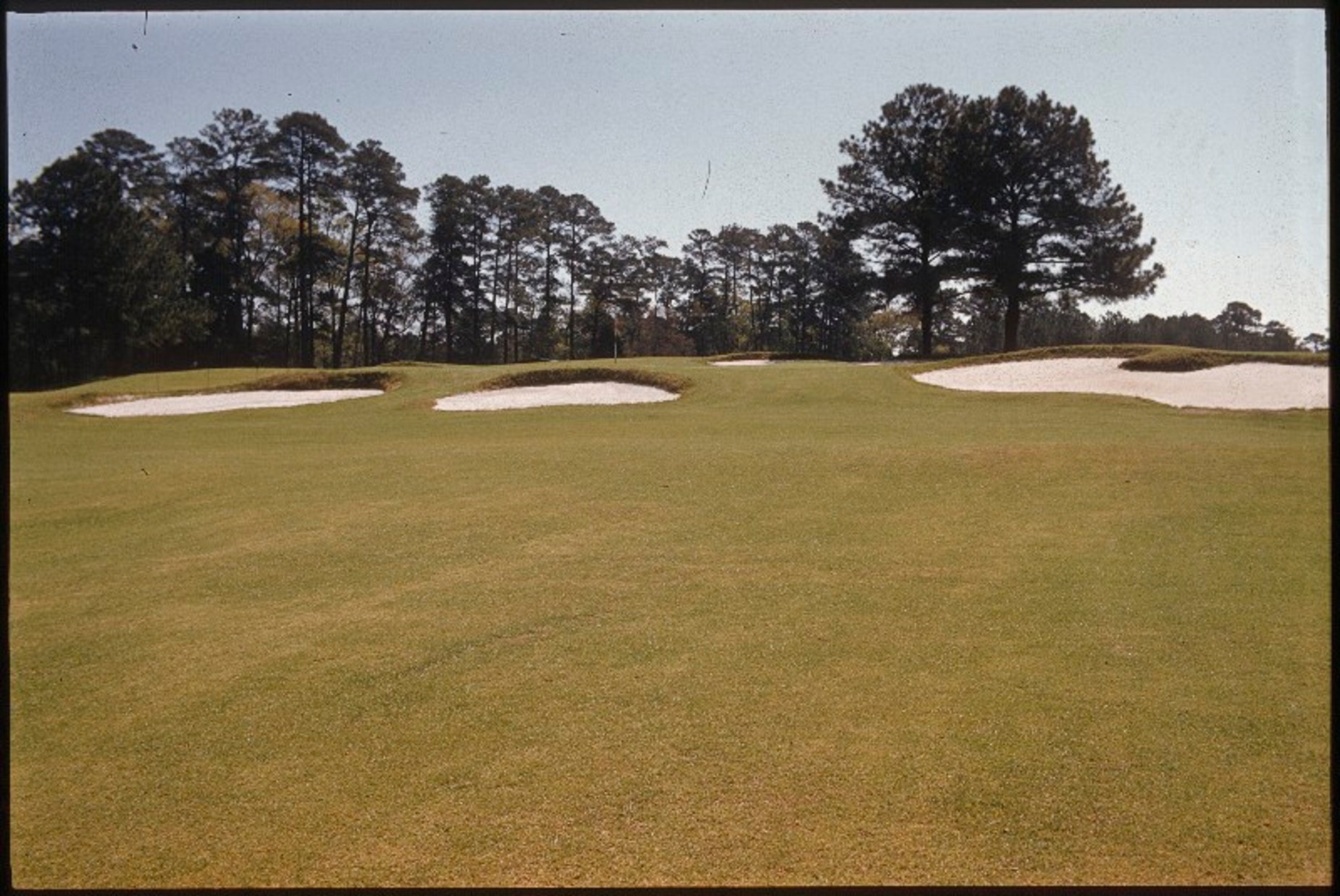

The par-5 eighth hole has undergone significant alterations. Much like the second hole, it too presented its fairway bunker as a central hazard, forcing players to choose a side. Two years after the following photo was taken, the club enlarged the bunker but moved it to the right edge of the fairway, making it a much simpler driving hole, thereby creating more opportunities for players to reach the green in two.

In 1955 the fairway bunker on the par-5 eighth hole still loomed in the middle of the fairway. The club moved it to the right side of the hole in 1957.

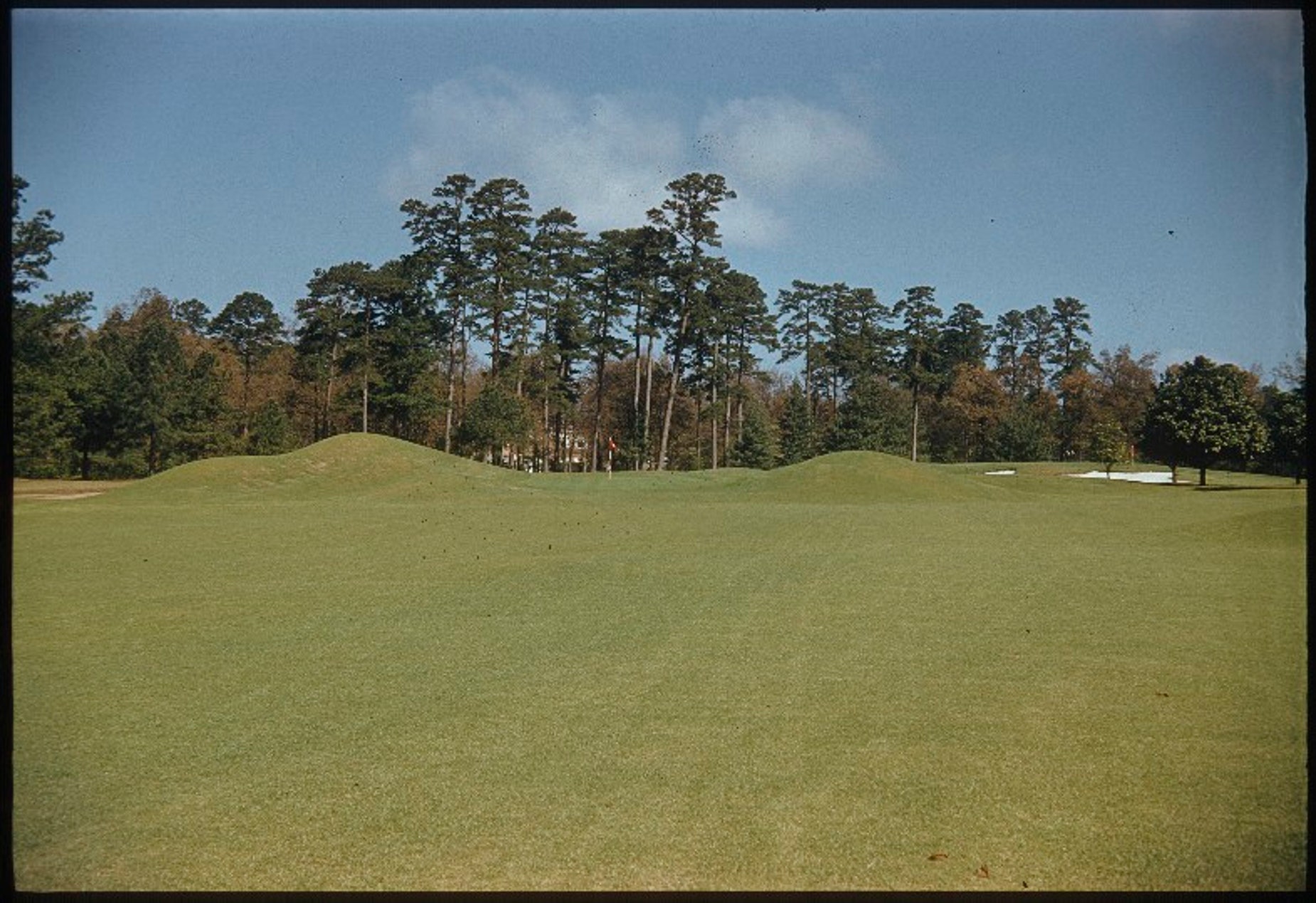

The green at the eighth appears similar in the following photo as it does now. But in 1956, at the direction of Clifford Roberts, the distinctive mounds were removed to increase spectator sightlines. What was left behind was a low, flat and awkwardly exposed putting surface out of character with the course’s complex green formations.

Though Bobby Jones disliked it, the hole remained in this state until the mid-1970s when Byron Nelson (along with consulting architect Joe Finger) was asked to help recreate the surrounding mounds from memory. The club presumably did not have access to this slide.

The distinctive mounds surrounding the green at No. 8, before they were taken down.

The eighth green as seen in 1956.

Over the years Augusta National has continued to add length by shifting and building new tees. Perhaps the most significant odyssey has been the tee complex at the par-4 11th. They were initially located above and behind the 10th green, then were moved above and to the green’s right. That created a rather sharp dogleg, and tournament players either hit irons off the tee or, occasionally, hit big slices that could travel down close to the green.

In 1950 the club shifted the tournament tee into the woods well to the left of and below the tenth green, straightening and lengthening the hole considerably, with room to extend almost indefinitely. This 1955 photo, however, appears as if it was taken from the old tee above and to the right of the tenth, indicating the degree of the left-to-right dogleg.

Here’s what it would’ve looked like from the old 11th tee, presumably.

The pond to the left of the 11th green was added four years prior to this picture, in 1951.

The 12th green as it appeared in 1955. Little has fundamentally changed other than fine-tuning the presentation and maintenance.

The green setting at the famous par-5 13th has been altered over the years as well. The bunkers to the rear of the green were remodeled prior to the 1955 Masters. In the early 1980s Jack Nicklaus would tinker more, adding a chipping swale between the bunkers and the putting surface.

In the opening round of the 1955 Masters, Sam Snead’s ball plugged in the newly remodelled bunker to the left of the green. It took four strokes to remove it. He took an 8 on the hole, sinking his chances to repeat as champion.

The final essential amendment the club has made to the course is the addition of trees in select areas. The most notable have been several rows of pines to the right of the 11th, pines pinching the landing zone on the 17th, and a cluster of pines impinging into the driving area on the left side of the par-5 15th. Previously players could gun for the green over the fronting pond from almost any position in the wide fairway. Now, the trees block a clear shot from drives pulled slightly left.

This is the look players had to the green at 15 until the early 2000s when trees were planted on the left. A bunker was added to the right of the green in 1957, at Ben Hogan’s suggestion.

Similarly, on the par-4 17th, once drives got past the now deceased Eisenhower Tree, the fairway was wide open, and players could use the width to select the best angle to approach the green depending on the hole location and conditions.

The Eisenhower Tree, no longer there, was hardly a factor in 1955.

Trees always surrounded the tee at the 18th, but as the tee has migrated back further, creating a chute-like tee shot, they’ve increasingly come into play and accentuated the need to shape the drive left-to-right.

The drive on 18 was far less intimidating before the tees were moved back.

A second fairway bunker was later added on 18, giving players even more to consider with their drives.

All golf courses morph and change throughout their lifetimes, but Augusta National has always been unique in its drive to match its conditioning and architecture to the changing demands of the Masters Tournament. Someday in the future we’ll look on today’s Augusta National and marvel at how differently it played and appeared.