By Shane Ryan

Faithful readers of Golf Digest in this strange summer won’t be surprised at the premise of this post. Back when the PGA Championship was supposed to be played in May, we ranked the 15 best PGA Championships of all-time. Back when the U.S. Open was supposed to be played in June, we ranked the 15 best U.S. Opens of all-time. And now, in a week that should have featured the 2020 Open Championship at Royal St. George’s, we’re bringing it back. If anything, this loss is felt the most acutely, since the Open was cancelled outright rather than pushed back to the late summer. The R&A has put together a nice substitute, though, in “The Open for the Ages,” which will air Sunday on the Golf Channel and use archival footage to imagine who would win a St. Andrews Open contested between the likes of Woods, Faldo, Nicklaus, Watson and more.

Just as with the previous posts, I’ve relied on the knowledge of an able historian to help me navigate this difficult question. My guru on this journey was Laurie Rae, Senior Curator at the R&A. Mr. Rae gave generously of his time to help winnow 148 Opens down to the “best” 15. The wisdom is all his, the perceived errors in ranking all mine. Let’s begin!

15. 1954, Peter Thomson, Royal Birkdale

If there are two historical golfers who merit more attention than they get, they are Peter Thomson and Bobby Locke. Rae didn’t want to use the word “forgotten,” but I will. At least in America, Thomson and Locke don’t get the credit they deserve, possibly because neither took home an American major and possibly because they missed the early peak of televised golf. But for a period in the 1950s, they were dominant at the Open, winning eight of 10 claret jugs between 1949 and 1958. The ’54 Open saw Thomson claim the first of his five, and become the first Australian to capture the championship. He and Locke were among those who fought it out in the final round at Royal Birkdale, and though I couldn’t find footage of Thomson’s sand recovery on 16, I did find this delightful newsreel showing the action of the final holes:

14. 1937, Henry Cotton, Carnoustie

Cotton’s triumph in 1934 was critical because it broke a streak of eight straight American wins, but his victory in ’37 was even more important in that he defeated the entirety of the U.S. Ryder Cup team, all of whom had stuck around to play at Carnoustie after their 8-4 win in late June. Cotton’s brilliant final-round 71 came in torrential conditions, and he later said that it was one of the finest rounds of his career. With that result, he overcame a three-shot 54-hole deficit to defeat among others Byron Nelson. According to Rae, the Englishman’s win “maintained British interest in the championship itself.”

13. 1992, Nick Faldo, Muirfield

Photo by Getty Images

As Rae noted, Faldo was in the prime of his prime, going for his fifth major in six years. He had won the Irish Open, and at the start of this Open, he looked fundamentally unstoppable. He set a 36-hole record, beat his own 54-hole record and came into the final round leading by four shots. It looked like a coronation, but it was not—a miserable stretch from 11 to 14 saw him lose three shots, American John Cook catching him and taking the lead on 16. For Faldo, this “dominant” Open now became about resilience. Pulling himself together, he birdied two of the final four holes and squeaked out a one-shot win—a testament to perseverance and even acceptance in the face of what must have been massive disappointment, and the greatest of his three Opens.

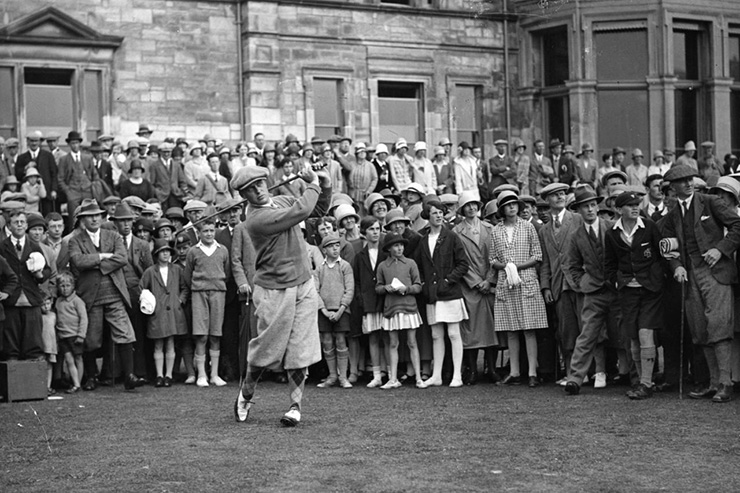

12. 1927, Bobby Jones, Old Course at St. Andrews

Photo by Topical Press Agency

In 1921, a younger, more impetuous Bobby Jones became so angry at his play in the third round at St. Andrews that he tore up his scorecard and withdrew after 11 holes. He then insulted the Old Course, and the St. Andrews press fired back, writing “Master Bobby is just a boy, and an ordinary boy at that.” This, then, was a kind of comeback story, because in the interval, Jones had come to love both the course and the town. And as fate would have it, they loved him back. When he won by six shots, he was carried off the green by a jubilant crowd, and even asked that his trophy be kept in Scotland with the R&A. By 1958, Jones had become just the second American “Freeman of the City” in St. Andrews, an honor he shared with none other than Ben Franklin. At that ceremony, Jones said of the Old Course that, “the more you study it, the more you love it, and the more you love it, the more you study it.”

11. 1953, Ben Hogan, Carnoustie

What do you call it when the greatest golfer of his generation comes over for the first and only time in his life, had just a week to prepare for the links style, improved in every round and won by four strokes? You call it Ben Hogan being Ben Hogan. The win capped an incredible year in major championships that also saw him capture the Masters and U.S. Open. He remains the only golfer to ever win those three events in the same year.

10. 1984, Seve Ballesteros, Old Course at St. Andrews

I’ll be honest: I’m in this one for the little dance Seve did when he sunk his putt on the 72nd hole. But historically, it merits top-10 status for the incredible drama at the end. Tom Watson, heading into the final round tied for the lead, had one of his greatest chances to win what would have been his record-tying sixth Open. With two holes to play, Watson and Seve were tied. Seve had a putt to take the lead on 18, while Watson was struggling to make his par on the road hole. The drama can best be seen starting at the 44:30 mark here:

Seve’s putt instigated a two-shot swing, perhaps one of the most famous in major championship golf, and added his name to the list of legendary winners at the Home of Golf.

9. 1896, Harry Vardon, Muirfield

This was the first of Vardon’s record six Open Championship wins, and though Rae said that every one of them was noteworthy enough to merit inclusion on the list, this one stood out because of how Vardon out-duelled his great rival J.H. Taylor over a 36-hole playoff. While the tournament’s final round came on a Thursday, the playoff wasn’t played until Saturday, since both Vardon and Taylor had to play a different 36-hole tournament on the Friday. Taylor won that one, but Vardon beat him at Muirfield. Taylor would win again, though, and in fact there was a 21-year period where Vardon, Taylor and James Braid won 16 championships between them. “They were the superstars of the Open,” Rae said.

8. 1868, Tom Morris Jr., Prestwick

At the time, Tom Morris Jr. (if you’re wondering, yes, I was slightly disappointed that Rae didn’t call him “Young Tom Morris”) was the youngest player in Open Championship history at 17. Prestwick was a 12-hole course, and the three rounds of the championship were all held on a single day. Morris Jr. set a record when he shot 51 on his first round, which was then bested by his father, who shot a 50 in the second round to take a one-shot lead. In the final round, though, Morris Jr. struck back, carding a 49 to beat his dad by three shots and win his first Open (which came with a massive £6 prize). This was the first of four straight Opens victories for Young Tom. As Rae pointed out, his story is all the more poignant because of his untimely death—Morris Jr. died on Christmas Day 1875 at age 24 from a pulmonary haemorrhage. “There were often very few competitors at this time,” Rae said, “but the golf was no less impressive and the champions no less dominant than they are today.” Morris Jr. remains the youngest Open winner in history, and his father is still the oldest.

7. 1972, Lee Trevino, Muirfield

In terms of the greatest shots in Open history, Trevino’s chip on 17 on Sunday ranks near the top. He had bungled the par 5 up to that point, and had hole out for par while Tony Jacklin, tied for the lead, had a 15-footer for birdie. It looked very much like Jacklin would head to the final hole with at least a one-shot edge. “I really felt, on the 17th, like I’d broken him,” Jacklin would later say. But in one of the great feats of match-play-within-stroke-play golf, Trevino turned the tables. Watch it play out, including Jacklin’s subsequent putts, starting at the 3:45 mark:

For Jacklin, who had watched Trevino hole out twice the day before, the loss was unbearable. Later, he said, “I was never the same again after that. I didn’t ever get my head around it—it definitely knocked the stuffing out of me somehow.” Jacklin had already won the Open in 1969, luckily, and would go on to transform the European Ryder Cup team as its captain, but what shows the emotional swings of better than that moment, which gave Trevino his second straight claret jug?

6. 1961, Arnold Palmer, Royal Troon

Photo by Bob Thomas

The impact here was more wide-ranging than any drama on the course, in which Palmer beat Dai Rees by a shot. What really mattered was that Palmer was the first American champion since Hogan in 1953, and his win did more to increase the status of the Open in America than anything before. According to Rae, a figure as beloved as Palmer, who believed so much in the history and importance of the Open as the oldest of the majors—this was his second trip over, having finished runner-up in ’60—and who wanted to win it so badly, fundamentally changed how the tournament was viewed in the eyes of American professionals. Many had stopped making the trip due to travel concerns, the low prize money and various other reasons. Palmer’s victory completely changed the perception. You can see it in the results—the long American dry spell was over, and in the 60 Opens that started with his win, Americans have won more than half. In his unique way, Palmer made it matter again.

5. 1970, Jack Nicklaus, Old Course at St. Andrews

It seems like the great ones always manage to get a win at St. Andrews, and for Nicklaus, this was the first of two. Interestingly, Doug Sanders only needed a par on the 18th hole to pull out the victory, but he missed a three-foot putt after being distracted by something in his eye line. Despite Sanders’s disappointment, he battled hard in the 18-hole playoff. It came down to the 18th hole, when Nicklaus took off his yellow sweater and hit one of the most famous shots of his career—a drive that actually flew over the green, travelling about 360 yards in total.

He chipped close from there, made his birdie putt and beat Sanders by one. At the end of this video, you can see Nicklaus, thrilled beyond self-control when his winning putt caught the right and edge and fell, actually threw his putter in the air, which nearly managed to hit Sanders as it fell.

4. 2016, Henrik Stenson, Royal Troon

“Some of the finest links golf you’d ever seen,” Rae said, and really, what more needs adding to this incredible fight between Stenson and Mickelson? It ended with Mickelson cooling off, just slightly, but Stenson never did, tying Johnny Miller’s major record (for a winner) with a final-round 63, and set a cumulative Open record with his 72-hole score in relation to par of 20 under. In many ways, it was also the best possible result—Mickelson had already won his Open in 2013, and Stenson was a player who deserved a major, but was starting to look like he might never get one. To win the Open, as a European, felt appropriate, and secured Stenson’s legacy. Plus, there was that record-setting final putt:

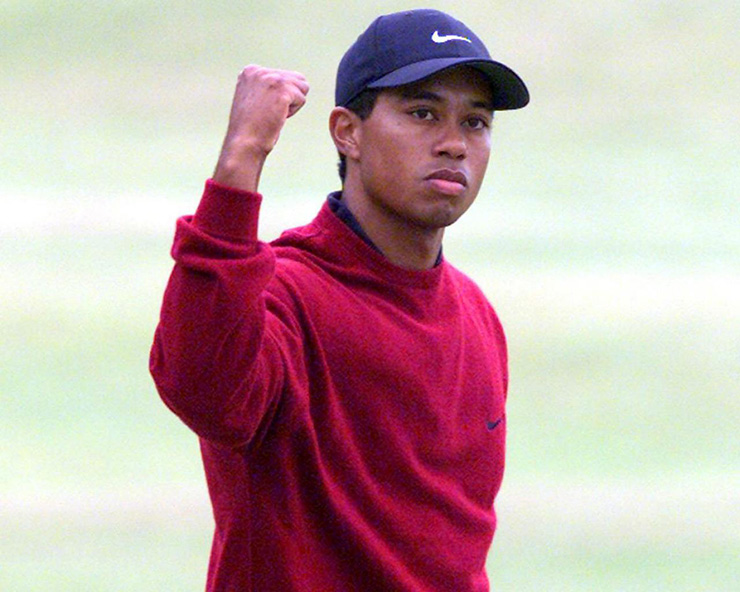

3. 2000, Tiger Woods, Old Course at St. Andrews

It seems like every major has its quintessential Transcendent Tiger year, in which the GOAT demolishes the field in ways that defy belief. The Masters in 1997, the U.S. Open in 2000, and maybe, at a stretch, the 2006 PGA. For the Open Championship, it was back in the greatest year of his great career, 2000. This was the “Millennium Open,” at the most famous course in the world, and 239,000 spectators watched him post a then-Open record 19 under, beating his nearest opponent by eight strokes and securing the career Grand Slam at the age of 24, the youngest to achieve the feat. Rae reminded me of an incredible facet of his performance: In 72 holes of superb course management, he didn’t find a single bunker. Remarkable anywhere, but especially at St. Andrews. And it’s also worth remembering that coming on the heels of his crushing Pebble Beach win, it legitimately seemed like Tiger might never lose again. This was a kind of dominance we’d never seen before, and haven’t since.

hoto by JONATHAN UTZ

2. 2019, Shane Lowry, Royal Portrush

Call it recency bias, and in fact I implied as much to Rae when he ranked it second on his list. I made a small note to adjust the ranking later—the privileges of a writer/dictator—but the more I thought about his argument, the more sense it made. The Open, more than any other major, is about history, and the significance of holding the first Open in Northern Ireland since 1951 is about as historical as it gets. In the interlude, that country fell into decades of religious and political conflict, and the symbolism of the R&A returning to Royal Portrush was enormous. To pull off a safe event, embraced by the people, and for an Irish golfer to win … well, it didn’t matter that the final day lacked drama. “It made your heartbeat quicker to witness it,” Rae told me, and in the end, I agree with him—the historical importance is unmatched.

1. Tom Watson, 1977, Turnberry

Students of the game knew No. 1 without having to scroll down, or else would have been enraged to find anything else in the top spot. “The Duel in the Sun” between Watson and Jack Nicklaus was simply one of the greatest golf spectacles ever, and one that, to quote Rae, “will forever be spoken about.” It was about the great rivalry between the two men, it was about the sportsmanship on display, and, of course, it was about the golf. “It went beyond natural chronology,” Rae said. “It was legendary.”

Watson, 27, and Nicklaus, 37, matched each other score for score in the first three rounds at Turnberry, hosting the Open for the first time, pulling away together where by the end, they were 10 shots better than anyone else in the field. In the closing stretch, where Watson birdied four of the final six holes for the dramatic victory, but perhaps it’s best summarized by a quote from that final-round Saturday, when Watson turned to Nicklaus and said, “this is what it’s all about isn’t it?”

“You bet it is,” Nicklaus replied.