Donald Miralle

A crowd packs the stands at the 18th green of the Torrey Pines South Course during the 2008 U.S. Open.

In hosting the PGA Championship, TPC Harding Park joins the list of municipal courses to embrace major championships—and benefit financially from holding them

By Tod Leonard

It never gets old for Jack Miller. He has been a resident of Farmingdale, N.Y., on Long Island for all of his 64 years and logged hundreds of rounds on the Bethpage State Park’s Black Course as both a player and caddie. He started looping in high school, and now he’s about to be eligible for Social Security, and something still stirs in him when he steps onto the first tee of the Black. He’s caddied for the rich, the famous and for Regular Joes, and he still looks for that recognition in their eyes that they’re about to experience something special.

“It’s like getting to play softball at Yankee Stadium,” Miller mused over the phone recently. “Somebody opens the door and lets you and your buddies in there, maybe slide into second base. That’s what it feels like.

“It pushes their buttons. I can see that.”

It’s true. The Black long had a reputation as the must-play course of the five in the state park. The masochists want to say they read the infamous warning sign begging for only “Highly Skilled Golfers,” went out and lost a box of Titleists in the choking fescue and felt like they’d gone 12 rounds with Muhammad Ali in his prime.

The thing is, though, the anticipation and the reverence was taken to another level over four days in the summer of 2002. When Tiger Woods putted out that Sunday in near darkness to secure his second U.S. Open title, amid an explosion of camera flashes, the first true “People’s Open” cemented Bethpage’s status as a bucket-list course for not just New Yorkers, not just Americans, but the world.

In turn, the legacy of what the USGA started at Bethpage, by taking a major championship beyond private and resort courses to a truly public facility, has continued and grown in subsequent years.

Torrey Pines, owned and operated by the city of San Diego, staged one of the most dramatic U.S. Opens in history in 2008 and is set to host the championship again next year. Bethpage followed with a second U.S. Open in 2009 and pulled off its first PGA Championship in 2019, with the Ryder Cup coming in 2025. County-operated Chambers Bay in Washington got its place in the sun in 2015 for the U.S. Open, and privately-owned, but high-end public track Erin Hills in Wisconsin followed as a host just two years later.

Now it’s TPC Harding Park’s turn. The gorgeous, cypress-lined municipal course that for many years was in rough shape until a massive, expensive renovation in the early 2000s has already hosted a couple of PGA Tour events and the Presidents Cup, and it draws the PGA Championship beginning on Thursday.

Sadly, because of the COVID-19 pandemic and a no-fans policy that the PGA of America had to implement, thousands who have weathered Harding Park’s golf challenges and San Francisco’s ever-changing climate won’t get to stand near the first tee or the 18th green and proudly say, “This is my course.”

They’ll have to do it in front of their television sets.

“To be put in the bucket with the facilities that can host major championships, and have the teeth to do that, it’s an honour,” said Dan Burke, the executive director of The First Tee of San Francisco, which calls Harding Park home. “That drives some upside, fiscally. And it’s more opportunity to bring value to your facility. People no longer just want to find a way to get on The Olympic Club [host of five majors] when they come to San Francisco. They can play a world-class facility and arrange a tee time for themselves.”

Torrey Pines’ South and North courses have hosted PGA Tour events since 1968, and Joe DeBock, the head pro since 1991, has always valued that. But he said even his own feelings about his work and the South Course, in particular, changed after the ’08 U.S. Open.

Fred Vuich

Fans surround Tiger Woods as he hits a shot on the 15th hole during his U.S. Open playoff victory over Rocco Mediate.

“It took it to a historical level,” DeBock said. “The interest is so much more broad. It’s worldwide, and we pulled off one of the greatest U.S. Opens of all time, so that doesn’t hurt.”

Encased in a prominent place in the Torrey Pines pro shop is a replica of the U.S. Open trophy, and DeBock enjoys sidling over to any group of people who are gawking at it. In fact, at Torrey, people pour out of their cars and never hold a club in their hand. What they leave with are fistfuls of hats and shirts. (The shop has been selling 2021 U.S. Open merchandise since November 2017.)

As much as you’d love to, you can’t do that kind of shopping at Oakmont or Winged Foot or Shinnecock Hills.

“Every single day at Torrey Pines I’m talking about the U.S. Open,” DeBock said. “And it all starts with Tiger, of course. The U.S. Open is a major, but I don’t think it would have exploded into what we have at Torrey Pines without Tiger. Tiger winning so many Farmers Opens [seven], his connection to Junior World [hosted annually at Torrey and won by Woods in his youth] … and then he wins the U.S. Open here. It’s a feather in our cap and pushed it way over the edge.”

At Torrey Pines, that means tee times seven days out on the phone-reservation system are snapped up in a couple of minutes. That’s for both the South and North courses, which combined host nearly 150,000 rounds per year. At Erin Hills, 40 miles northwest of Milwaukee, golfers are already making plans for next summer, to pay $320 to walk in peak season. We all know what devotees of Bethpage Black do—they sleep in their cars to get tee times.

Fred Vuich

Fans watch Phil Mickelson tee off from the roof of a building on the Bethpage Black Course during teh 2002 U.S. Open.

Popularity comes with a price tag. Golfers are paying higher prices than ever to play the public major venues, though the locals at most places get a considerable break.

At Bethpage, New York state residents are charged $65-$75 for the walking-only Black, while visitors pay $130-$150. That seems pretty reasonable, though for perspective, it cost $25 to play the Black on the weekend in 1996. The Black’s a bargain compared to Torrey Pines, where out-of-towners hand over $202-$252 to walk the South (electric carts are $40), while San Diego city residents seemingly get an attractive deal ($63-$78).

Erin Hills, which got rising star Brooks Koepka as its U.S. Open champ in 2017, ends up being more comparably priced to its Wisconsin resort neighbor, Whistling Straits (which has hosted three PGAs), than it does the munys. And it’s more exclusive, too. There is no public access; you can’t even enter the gate without a tee time.

“The bottom line is, it’s just for golfers,” said Rich Tock, Erin Hills’ longtime director of golf who now serves primarily as an “ambassador.”

“We’re a boutique, not a factory,” he added.

Ross Kinnaird

In 2017, massive crowds were drawn to Erin Hills, where the first U.S. Open staged in Wisconsin was staged.

Talk about a major having impact on your golf course: Erin Hills may not exist if not for attracting the U.S. Open. Before wealthy businessman Andy Ziegler purchased the facility in 2009, it was in disastrous financial condition. The original owner, Bob Lang, lost millions trying to get the course up and running while hoping to attract a U.S. Open. But it was Ziegler’s money and makeover of the grounds that ultimately buoyed the USGA’s confidence in the site.

“They may not have survived,” Tock said. “Knowing all of the golf courses that were closing at that time, a developer might have bought it and put houses in. When Andy Ziegler got there, we got rid of houses!”

So committed was Ziegler to staging an attractive U.S. Open that he didn’t even open the course for play in the spring of ’17, leaving on the table huge financial gains, with public golfers salivating for a preview of the venue.

“When we told [USGA CEO] Mike Davis that we were going to do that, he about fell out of his chair,” Tock said with a laugh.

For the financial bottom line, hosting a major can produce a long-term windfall. Torrey Pines’ numbers, for example, would be the envy of virtually every course operator. In the 2020 fiscal year, which ended in June, Torrey had revenues of $16.9 million and a net profit of $4.8 million. San Diego’s other two municipal facilities lost a combined $1 million, so Torrey Pines goes a long way toward supporting their existence. All of the profits go back into a golf enterprise fund, which currently has a balance of $10 million, with another $15 million in improvements on the table.

Robert Beck

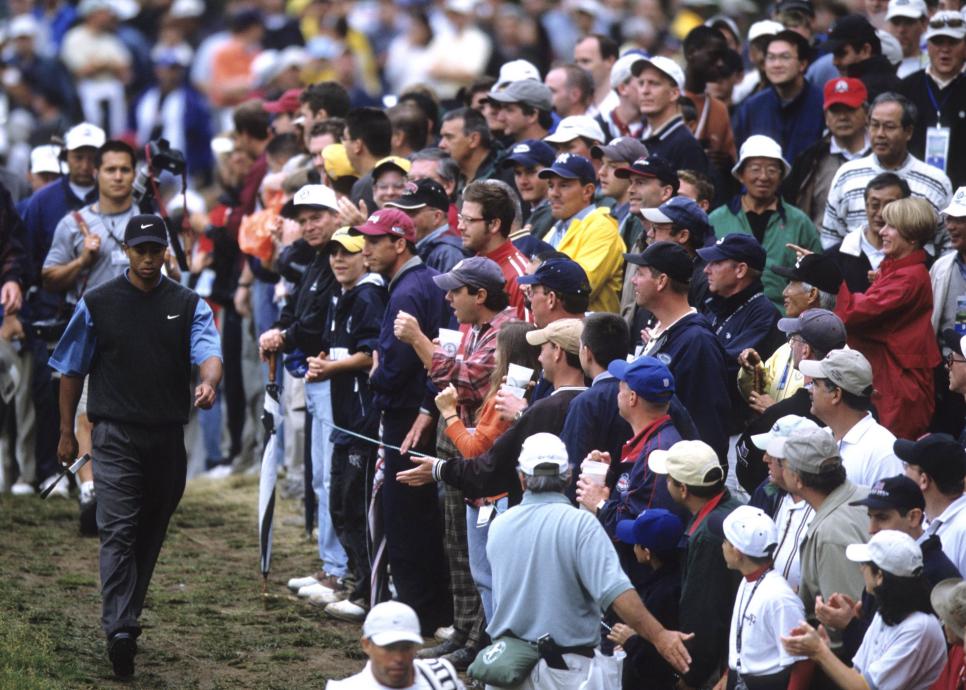

Tiger Woods walks close to the fans at Bethpage Black on the Saturday of the 2002 U.S. Open.

A public course hosting a major also brings an advantage for those who want to understand how the business of majors works. The USGA’s agreement with Torrey Pines is on the public record, and the financial facts are these: The USGA will pay San Diego $2.5 million (part of which will go for lost revenue while the courses are closed), share 20 percent of the hospitality revenue with the city and add another $350,000 for services such as police and fire patrol.

“I think if you look at the costs the city has for the All-Star Game, or a Super Bowl, or a major convention, the U.S. Open is a screaming deal,” said Mark Marney, San Diego’s golf manager. “There is some inconvenience in the course being shut down, but we’re getting the name association with our facility and all that goes with it.”

Some weigh the costs and benefits of a major more warily. Michael Zucchet, a former San Diego city councilman who also is a longtime member of the Torrey Pines men’s club, said the benefits also create the drawbacks.

While praising the financial gains and the consistently good condition of the courses, he said, “My biggest concern is the loss of autonomy or ownership of the course. You’ve got the USGA calling the shots at ‘our’ course. They’re doing what’s best for the USGA, not the people of San Diego.”

Zucchet points out that more than $12 million was spent the last couple of years on irrigation improvements and course alterations to the South. Marney said the majority of that construction was planned and necessary to maintain the South to modern standards, whether it was going to host another U.S. Open or not. He said the USGA did not require the work.

Zucchet also noted that the course became considerably more difficult for average golfers to play after its 2001 renovation and that the challenge basically cut in half the option for Torrey golfers. For some, it’s the North Course or bust now.

“Now you have to play a frickin’ U.S. Open course,” he said. “That’s good if you enjoy beating your head against the wall every day. It’s maybe not what everyone wants in a municipal golf course. … Not to sound like an old man, but it’s not the Torrey Pines I grew up on playing a thousand times.”

It seems as long as golf’s top organizations choose municipal courses on which to hold majors, there will be that debate. For the Bethpage caddie, Miller—who became something of a local celebrity when he was the only local to tote a bag in the 2019 PGA—the benefits to not only the state golf courses, but his town are clear. He recalls a time a few decades ago when Farmingdale was a “ghost town” with a couple of marginal restaurants and a boarded-up movie theater.

The major championships on the Black changed that, he contends.

“Tremendously,” Miller said. “There are nice hotels built above the shops and about 20 restaurants. The town is just jumpin’. The train rolls in here, people get off, and they walk right up to the golf course.

“The town was just a town, and now the whole world comes here year after year.”