By Ron Whitten

Pete Dye, the man who reinvented golf course design, is gone, succumbing to that bastard Father Time at age 94. He was a legend, a Hall of Famer, a showman and a friend. He built over one hundred golf courses, but his real legacy is how those courses impacted the game and millions who play it.

Before Pete, golf architects mass-produced their products. Assembly lines of bulldozers stretched from coast to coast and chugged out facsimiles of the latest fashions. Some would eventually be deemed top-flight tests of golf, but all bore trademarks of one another.

Pete was a disruptor 50 years before that became a corporate buzzword. We called his style of design “target golf,” for it embraced abrupt change in its landforms, its sink-or-swim choices, its death-or-glory options, its my-way-or-the-highway reasoning.

Pete Dye instilled emotion into a previously staid game. That was an inevitable byproduct of his formative years. He was a teenage paratrooper during the last years of World War II, so he wanted golfers to feel the same sweaty palms and pit in the stomach as they faced their personal moments of truth, off a tee or into a green. He sold life insurance for a living, so he made golfers risk everything for a decent return.

Pete played golf with Donald Ross and Donald Trump and mined nuggets of knowledge from them both. He was a reactionary when golf was especially conservative. Pete threw a monkey wrench into every golfer’s swing. Where other architects strove to make golfers contemplate options before they faced a shot, Pete made golfers doubt; doubt their own eyes, their own capabilities, their own passion for the game. He did so with invention, deception and railroad ties. He found inspiration from Popular Mechanics, Model Railroader and an army manual.

Yes, early in his career he admitted to imitating famous predecessors — MacKenzie, Ross, Langford and Raynor, and contemporaries like Trent Jones. Later, after a tour of Scotland, he claimed allegiance to a far earlier generation. Yet Pete Dye architecture was ultimately original, not quite like anything golfers had ever seen before or since.

Midwest born and bred, Middle American to the core, Pete’s originality conjured up the thrills of a county fair – the Tilt-a-Whirl in a triple-level green that plunged side to side and downhill; the Fun House in a zigzag par 5 with a putting green perched on a fault line 20 feet above a hazard; the Dunk Tank in an island green glaring like the eye of a gator in a deep dark pool.

His wife, Alice, was the more successful competitive golfer, the better writer (ghosting every early article bearing his byline) and the smarter businessperson. Pete owed much his fame and fortune to her tireless promotion, and it was tragic when she passed away in early 2019 at age 91.

Pete wanted those who constructed his courses to be absolutely devoid of any knowledge about golf, lest they shaped holes that would look and play like everything else on the block. Dig me a swimming pool, he’d tell a crew when he wanted a bunker. Build me a giant birthday cake, he’d say when he wanted an elevated green. Occasionally, he’d wander off and the crew would be left to their own devices. A green famously created from dune buggy races in the sand was one result.

What was most impressive about his 50-year design career was that Pete constantly rethought his architecture. He began with a few modest designs where his attention focused on shaping sprawling, rolling greens. Then came some meaningful projects in the Midwest: 36 new holes for the relocated Des Moines Golf & Country Club, Radrick Farms for the University of Michigan and Pete’s first great golf course – Crooked Stick near Indianapolis, which he organized and where he would never stop tinkering. Then he entered a new phase, building ground-hugging, lay-of-the-land layouts, short and tight with greens the size of porch mats: The Golf Club near Columbus, Ohio, which seduced Jack Nicklaus into a second career long before he ever realized he could make money from it, then Harbour Town Golf Links on Hilton Head Island, one of five collaborations Pete did with Jack. It possessed what Dan Jenkins perceptively identified as “instant character.” In the early 1970s he produced the sublime Teeth of the Dog in the Dominican Republic, literally sketched in the dirt and scratched into reality by a legion of Dominicans hand-planting individual tufts of turf.

But when pro golfers became Schwarzeneggers, Pete resorted to utter upheaval of the land, with bazooka-length holes edged by massive battlefields of bunkers, and greens girdled by earth sculptures he called grenade attacks. These are his most distinctive and recognizable layouts: the Stadium Courses at PGA West and TPC Sawgrass, the Straits at Whistling Straits, the Dye at French Lick. Throughout his career, golfers could never play their usual game on his designs; they had to leave their comfort levels at the first tee.

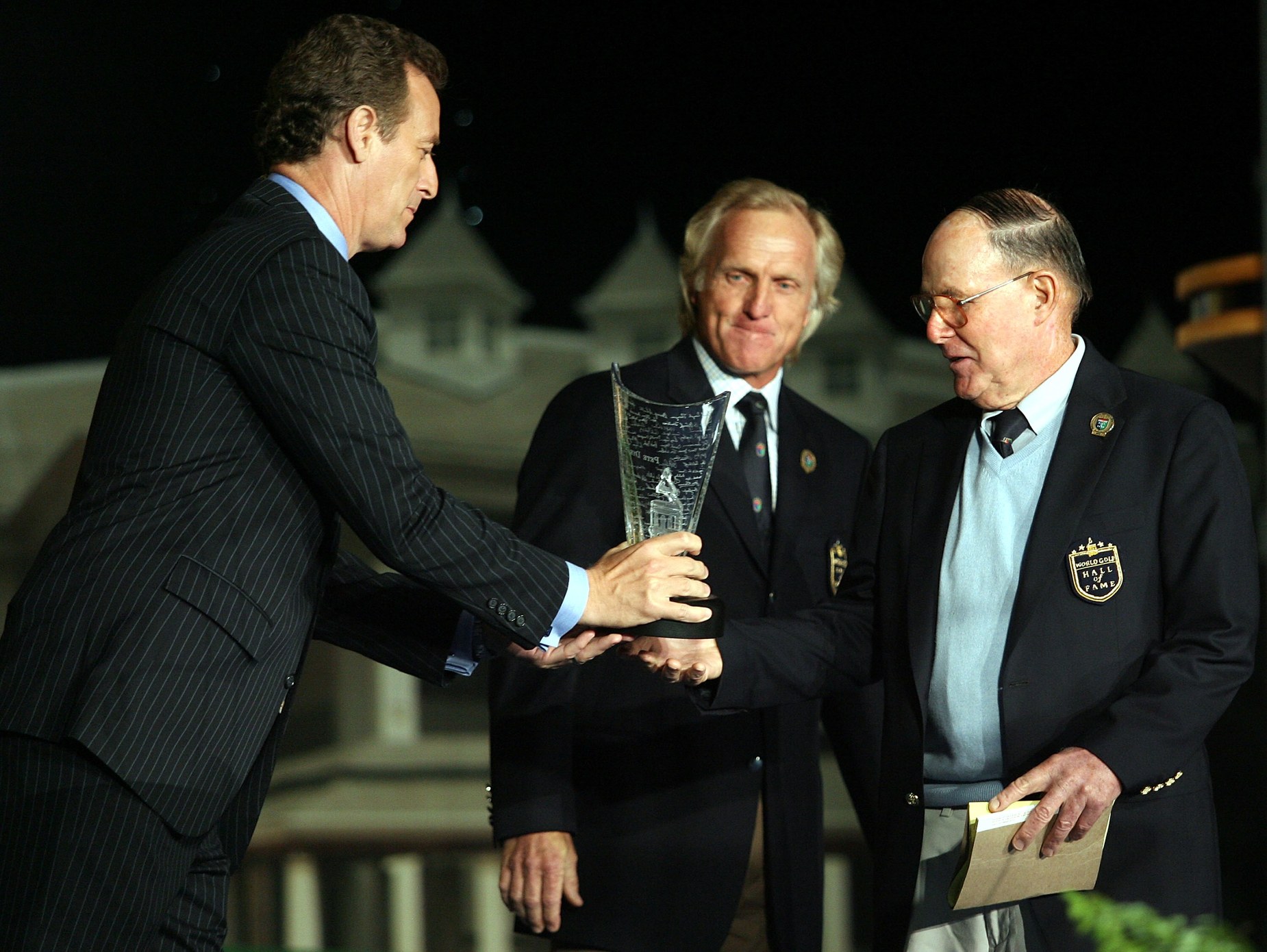

Dye at his World Golf Hall Of Fame Induction

Photo: Marc Serota

Pete’s unorthodoxy captured the fancy of magazine editors and at least one Tour Commissioner, Deane Beman, but it soured many who played the game for a living and expected satisfying results for even those most marginal of shots. Despite that animosity, or maybe because of it, Dye’s designs dominated magazine course rankings and the PGA Tour schedule, with the occasional major at Oak Tree, Crooked Stick, Whistling Straits and Blackwolf Run.

Pete never called himself a golf course architect because that implied education and technical training that he did not possess. He didn’t even like calling himself a golf course designer, for he lacked artistic talent and his sketches of golf holes looked like stick figures. Pete called himself a golf course builder, a guy who messed around in the dirt until he’d come up with something different than anyone had played before. He worked by trial and error, a very ineffective manner if you’re footing the bill, but acceptable if you’re looking for true art. It was particularly inefficient when Pete would rip up a fully grassed and playable golf hole because he just had another brainstorm.

He genuinely thought his steep slopes and black hole bunkers could be easily maintained, although countless course superintendents felt otherwise. So he fiddled with unconventional grasses that he felt would need less TLC. Those experiments fizzled and today his courses bear the same strains of conventional turf as anyone else. Likewise, his idea of hooking pumps to underground pipes produced efficient drainage on flat courses but created geysers on hilly ones.

Dye’s inventiveness inspired a baby boomer generation of golf architects who worked for him with near-religious fervour, hence their nickname, The Dye-ciples. Some embraced his approach and style to such a degree that they mostly reproduced his designs over and over – his sons Perry (born 1952) and P.B. (1955) come to mind, as well as the late David Pfaff, David Postlethwait and Tim Liddy. Hence, they never fully emerged from his overpowering limelight.

Others adopted his work ethic but not his schtick and achieved grand acclaim – Bill Coore, Tom Doak, Bobby Weed, Lee Schmidt, Brian Curley. But if any are remembered a hundred years from now, it will be partly because they got their starts working for Pete Dye.

What Pete did better than any other designer before or since was to throw back the curtain and reveal the wizard at the controls. In his mind, Mother Nature was never really a golf course architect. She merely provided foundations upon which humans would endeavour. Other designers tried to fool golfers into thinking Mother Nature truly created their courses. Pete made sure every golfer knew Pete produced his puzzles; Mother Nature would never have puckered a sand bunker atop a giant anthill.

In the end, Dye perished the way many a creative person has, from sheer exhaustion of the imagination. It is both a sad and sobering time. Golf design shall never see another like him.