We don’t follow golf the way we used to, and no tournament has showcased our changing habits better than the first major of the year.

By John Strege

History, without anyone there to chronicle it, is myth without a byline. It recalls that famous old thought experiment, that if a loblolly pine falls at Augusta National and no one is there to hear it …

Bobby Jones understood this explicitly. He acknowledged the importance of the press with his preface in the book, The Bobby Jones Story, by Grantland Rice, from the writings of O.B. Keeler, an Atlanta sportswriter who chronicled all things Jones.

“To gain any sort of fame it isn’t enough to do the job. There must be someone to spread the news,” Jones wrote, his homage to Keeler’s work.

How Masters news is spread has changed radically from the first Augusta National Invitation Tournament in 1934, when sportswriters, via Western Union operators on site, filed stories that were readied for print on Linotype machines and weren’t read until the following morning or evening. Newspapers virtually had a monopoly on the dissemination of news then.

What hasn’t changed is Augusta National’s commitment to media and how it contributes to the Masters, based on Jones’ recognition of its importance. The club even erected a working monument to it, a palatial new media center, or Press Building as it’s called, that opened at last year’s Masters.

“We had a very simple goal,” Billy Payne, Augusta National’s chairman at the time, said in a news conference. “To build for you the finest working environment in all of sport, not just in golf, to create a facility that not only expedites and enhances the creation of your work product, but one that acknowledges your long-term importance to the success of the Masters.

“We are fully aware that over the decades, the magic of your words, the pictures literally painted by your compelling narratives, are largely responsible for the universal reverence and appeal of the Masters.”

The metamorphosis of how the public has followed the tournament over those decades correlates to the Masters’ own transformation. In 1934, it was held at what then was an outpost, 145 miles from Atlanta and accessed via a two-lane road. Today, it represents the center of the golf universe, accessed from anywhere in the world via the information superhighway.

Here’s how it got there:

Augusta National Clifford Roberts (second from left) and Bobby Jones both recognized that the success of their new golf club hinged to a great degree on media exposure.

1934

The Great Depression was neither a good time to open a private club nor to attempt to launch a golf tournament, yet Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts did both. They lobbied to bring the U.S. Open to Augusta National, fully aware that doing so would double as a membership drive that would help with their sagging bottom line. The United States Golf Association, however, declined, so Jones and Roberts chose to start their own tournament, the Augusta National Invitation Tournament, which debuted in 1934.

Jones was convinced to come out of retirement to play one tournament as an inducement to pique interest. They, too, had a valuable asset in Grantland Rice, the most prominent sportswriter in the country, who was a founding member at Augusta National. In an effort to get the media on board, Rice’s idea was to convince baseball writers heading north via train at the end of spring training in Florida to make a stop at Augusta to cover Jones’ return to competition.

It apparently worked, at least according to Rice. “Eighteen thousand more words were telegraphed from the Augusta battlefield than the last United States Open at Chicago sent spinning over the wires,” Rice wrote in American Golfer, the magazine he edited.

The first Augusta National Invitation had a radio audience, too—CBS Radio broadcast it nationally, with a then-notable golf dignitary at the mic.

“It was the sort of tournament Mr. Herbert H. Ramsay, former president of the United States Golf Association, who also put on a swell job of broadcasting, pronounced it one of the greatest golf shows he had ever seen,” Rice wrote.

1935

Yet it was the 1935 Augusta National Invitation that began the Masters’ ascent toward major-championship status. It was the year that Gene Sarazen holed his 3-wood second shot at the par-5 15th in the final round, erasing a two-stroke deficit that allowed him to win in a playoff.

Again, it was almost exclusively incumbent on newspapers to inform the populace about the tournament and Sarazen’s miraculous shot, and Rice, among the most widely read sportswriters in the country, called it “the shot heard ’round the world.” It was a phrase that helped give the tournament a boost toward acceptance as a bona fide competition.

Rice wrote in American Golfer: “The second Augusta National tournament was a sure tip that this tournament will now take its place among the most important of the year in golf. The presence of Bobby Jones gave it the initial start it needed. Now it will ride on its own …”

Augusta National

Gene Sarazen’s double eagle and subsequent victory in 1935 was the first Masters moment that commanded national attention.

1939

Newspapers again used their influence to elevate the tournament in the hierarchy of golf. From the outset, Roberts and Rice preferred the tournament be called the Masters, but Jones was opposed. Hence it was known as the Augusta National Invitation, though Rice had called it the Masters in his reportage in 1934. By 1939, it officially became known as the Masters.

“As for how the name Masters came into being, no one is really sure,” Dan Jenkins wrote in Sports Illustrated. “Jones liked to give both Grantland Rice and his friend Clifford Roberts the credit, but in any case he once said, revealing his subtle humor, ‘I must admit that the name was rather born of immodesty.’ ”

Augusta National

In the days before television, Masters coverage was primarily the domain of newspaper reporters, many of whom stopped at Augusta on their way home from covering spring training.

1946-’47

When the war ended and the club was preparing for the Masters to resume in 1946, Roberts already was looking ahead to televising the tournament, though the medium was still in its infancy.

“I don’t suppose anyone will be ready to do anything in the way of television,” Roberts wrote in 1946, “but if they can by next April, I will naturally want to hear about it.”

CBS had not renewed its Masters radio contract, and when NBC stepped into the void, it also received the rights to televise the tournament. In the run-up to the ’47 Masters, however, NBC declined to televise it. It wasn’t until 1954 that a golf tournament, the U.S. Open at Baltusrol, was televised live nationally, by NBC, further piquing Roberts’ interest

1953

The print media bid adieu to the press tent and moved into a Quonset hut that was “tucked behind shrubs on the first fairway with long wooden tables where Herbert Warren Wind and company typed away and occasionally had to get everything off the floor when heavy rains flooded through the front door,” Scott Michaux of the Augusta Chronicle wrote.

The first Masters telecast featured cameras on holes 15 through 18.

1956

NBC by now was televising the U.S. Open, but was disinterested in airing the Masters and chose to end its association with the tournament. CBS immediately came aboard with the first of what now is 63 consecutive years working with a one-year contract.

CBS had six cameras there, on four holes, the 15th through 18th, and the tournament aired for a half-hour on Friday and one hour on Saturday and Sunday.

“The first Masters broadcast was uneven in the extreme … but it was a hit with golf fans,” David Owen wrote in his book, The Making of the Masters: Clifford Roberts, Augusta National, and Golf’s Most Prestigious Tournament. It had an estimated 10 million viewers. “[A]nd Roberts later learned that in the grill rooms of golf clubs all over the country, groups of golfers had gathered to catch glimpses of the action and of the course.”

1957

Augusta National’s television committee suggested in the wake of the tournament that an effort should be made to show the 12th hole and 13th green, the “most picturesque part of our golf course,” it said, according to a story by Owen in Golf Digest. CBS declined.

Irony alert: Augusta National in later years took incessant grief from viewers and media for stubbornly refusing to televise the front nine, yet initially it was the club arguing for expanding coverage.

1958

The Masters’ tradition of “limited commercial interruptions” that continues to this day began with the 1958 telecast, when American Express came aboard as its first sponsor. “The average golf fan takes his golf pretty seriously,” Roberts wrote. “Nothing but extreme annoyance could result from untimely, too long or too frequent commercials.”

Arguably no figure other than Roberts or Jones was more important in elevating the Masters to its current status than Frank Chirkinian (right) of CBS, who introduced the concept of scoring in relation to par.

1960

Frank Chirkinian had begun producing CBS’ Masters telecasts the year before and his impact was immediate. In 1960, he introduced scoring as we follow it today, in relation to par, rather than total strokes. Here was his explanation:

“The first year we did the Masters was 1959, and it was maddening,” he told Loran Smith of Athens Online. “The scores were posted with cumulative scores. When a player finished a hole and his cumulative score at that point was 215, that was what went up on the scoreboard. You might have one player with 215 in a playing group and the other player’s cumulative score might be 240. Nobody knew what was going on.”

1966

Roberts, according to Owen’s book, had been lobbying CBS for years to broadcast the Masters in color and was even tempted to abandon the network over its objections. Finally, CBS acquiesced. A year later, the inimitable Dan Jenkins, in Sports Illustrated, wrote, “And the whole scene was awash in color, Augusta-CBS color, which, of course, is better than the less vivid hues of God, though perhaps not as good as NBC’s.”

Related: Bob Goalby, a controversial Masters winner, finds peace 50 years later

1973

CBS anchor Jack Whitaker, who Clifford Roberts reportedly banned after the 1966 broadcast for having referred to the crowd at Augusta National as “a mob,” returned to the CBS team, working the 16th hole. “Whitaker recalls that Roberts greeted him warmly and said, ‘Young man, we are very fortunate that you are here,’ ” Owen wrote. Whitaker remained on the telecasts until he left for ABC in 1981.

That was the year, incidentally, CBS finally showed the 12th hole—16 years after the Masters television committee had suggested that CBS show it.

Augusta National

Television coverage of the Masters expanded to include the back nine, but the tournament held out on showing more for several years.

1982

The Masters became the first major championship to receive live coverage on cable television, with USA Network providing first and second-round coverage, two hours each day.

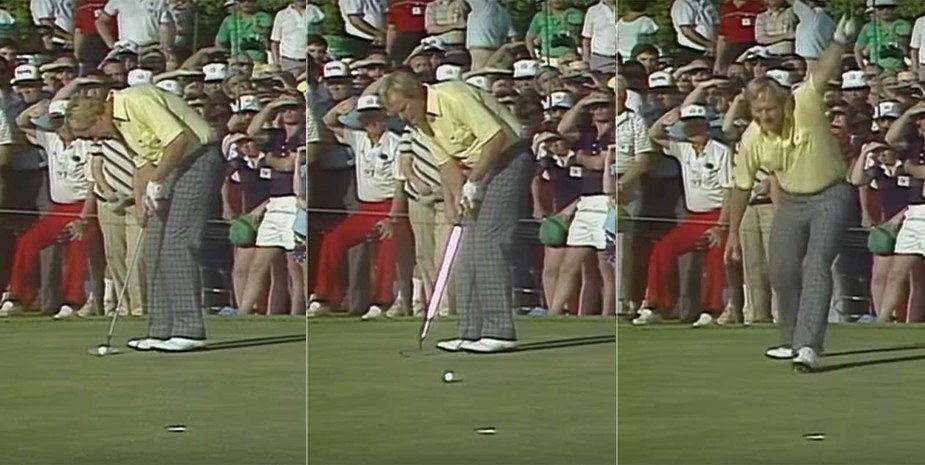

Remarkable to think now that at one point on Sunday in 1986, CBS producers weren’t convinced Jack Nicklaus was worthy of coverage.

1986

When CBS’ telecast of the final round began, Jack Nicklaus was not a factor. Obviously, there was no Internet then, no way to check scores or to know anything going on other than what CBS was showing and executive producer Frank Chirkinian had no interest in showing Nicklaus. It was more than 24 minutes into the telecast when CBS showed him for the first time, another 15 minutes or so before showing him the second time.

Chris Millard recounted in Golf Digest how the exchange between Chirkinian and his young associate director Lance Barrow went down:

“The protégé felt compelled to advise his boss of Nicklaus’ stirring. Feeding the cantankerous Chirkinian tidbits was like feeding a shark—things could go badly—but Barrow pressed ahead. Barrow was seated only a few feet to Chirkinian’s left in the sun-starved production truck, lit by the blue haze of some 60 television monitors. ‘Frank,’ said Barrow, ‘we’ve got Nicklaus with a birdie at nine.’

“Predictably, the boss was dismissive. ‘I don’t need him,’ Chirkinian snapped. Nicklaus proceeded to birdie No. 10 with a 25-foot bomb. The husky, intrepid Barrow, nicknamed ‘Buddha’ by Chirkinian, again tapped his boss on the leg. ‘We’ve got Nicklaus with a birdie at 10, Frank.’

“‘I don’t need him,’ growled Chirkinian. ‘Quit telling me about Jack! Nicklaus means nothing in this golf tournament!’

“When Nicklaus birdied the 11th hole, Barrow again summoned his nerve. He gently tapped his mentor on the leg and said, ‘Frank, uh, I know that Jack means nothing to this golf tournament, but he just birdied 11 … and he’s two off the lead.’

“Chirkinian glanced at Barrow and said, ‘Cue it up, Buddha.’”

CBS did show the birdie at 10, on tape. “Earlier, Jack Nicklaus for birdie to go four-under par,” CBS’ Bob Murphy said. When the putt dropped, Murphy exclaimed, “and the Bear, the Bear is stalking.”

And the rest is broadcast history, including Verne Lundquist’s simple, but enduring call when Nicklaus holed a birdie putt at 17 to take the outright lead: “Yessir!”

Meanwhile, Jenkins in Golf Digest summed up the collective angst among the writers in the Quonset hut afterwards: “On that final afternoon of the Masters Tournament, Nicklaus’ deeds were so unexpectedly heroic, dramatic and historic, the taking of his sixth green jacket would certainly rank as the biggest golf story since Jones’ Grand Slam of 1930. That Sunday night, writers from all corners of the globe were last seen sitting limply at their machines, muttering, ‘It’s too big for me.’ ”

Augusta National

The Media Center at the Masters that stood from 1990 through the 2016 tournament.

1990

The media finally moved out of the Quonset hut and into a state-of-the-art building, featuring amphitheater seating that looked down upon a massive scoreboard. It was an estimated five times the size of the 3,200-square-foot Quonset hut.

1996

Masters.org (now Masters.com) debuted with a simple homepage, featuring portals to a leader board, players, the course and news.

1997

Tiger Woods, 21, ushered in a new era of domination and viewer/reader interest with his 12-stroke victory. An estimated 43 million viewers were watching the final round.

Howard Manly of the Boston Globe provided a revealing example of the appeal Tiger had even on those who had never watched golf before:

“For as long as he can remember, Eugene Rivers has gone to church on Sundays, morning, noon, and night. And since he has been Rev. Rivers, at a Pentecostal church in Dorchester, that practice has continued.

“That is, until last Sunday, when he dashed out of an afternoon dinner fellowship with his congregation to watch Tiger Woods on television in the Masters. ‘I have never watched golf in my entire life,’ said Rev. Rivers, 47. ‘It’s such a sleepy little game and could probably put insomniacs to sleep. But Tiger is the reason to watch golf now. He has given me a reason.’ ”

Woods’ win in 1997 drew 43 million viewers for the final round.

1998

The year marked the end of Jackson Stephens’ reign as the chairman of Augusta National during which he had grappled with the media over his refusal to allow front-nine television coverage of the Masters leaders. In one such memorable exchange, in response to when it might happen, he explained, “progress is slow.”

Why?

“Well, progress is slow because we don’t want it to happen,” he replied.

His most memorable rejoinder, however, was in response to having been asked what was intended to be a gotcha question. “Do you watch the Super Bowl?”

“Fourth quarter,” Stephens said.

2002

Hootie Johnson, who succeeded Stephens as the chairman of Augusta National, acquiesced to the ongoing plea to show the leaders play the full 18 holes, extending CBS’ final-round coverage on Sunday by 90 minutes.

“To see the leaders from the first shot on, every step of the way, is going to be very special,” CBS anchor Jim Nantz said.

The change in attitude was brought about by the 2000 Masters, when a rain delay in the third round prohibited the leaders from teeing off until CBS had already come on the air.

“The network had coverage of every shot until darkness suspended play with Vijay Singh and David Duval on the 15th hole,” the Associated Press wrote. “It proved to be pivotal toward getting more coverage this year.

“ ‘Part of the reason the club feels comfortable now with 18-hole coverage was because the coverage that Saturday was so positive,’ CBS Sports president Sean McManus said.”

It was a welcome concession by Augusta National. Tiger Woods won the Masters for the second straight year, defeating Retief Goosen by three.

Getty Images

Protests over Augusta National’s membership policies led the club to make the bold decision to conduct the tournament telecast without commercial sponsors in 2003 and 2004.

2003-’04

The Masters’ telecasts had no commercials, its response to the Martha Burk controversy over Augusta National having no women members. It did so to protect its three sponsors, IBM, CitiGroup and Coca-Cola, from having to endure pressure from women’s groups.

“This year’s telecast will be conducted by the Masters Tournament,” Augusta chairman Hootie Johnson said in a statement. “We appreciate everything our media sponsors have done for us, but under the circumstances, we think it is important to take this step.”

2006

“Amen Corner Live” debuted at Masters.org in conjunction with CBS Sportsline, offering 22 hours over four days of live coverage of the 11th, 12th and 13th holes.

“The importance and use of the Internet continues to grow, and we think this is another service to our patrons,” Hootie Johnson said. “The ability to see live action at Amen Corner is something very special.”

Johnson and Augusta National were on the Internet broadband wagon. By April 6, 2006, the day the Masters began, 42 percent of adults had home high-speed broadband, according to Pew Research Center, and “Amen Corner Live” was an instant hit. CBS Sports reported more than 1.3 million video streams in the first two days and that the average time spent viewing “Amen Corner Live” was more than 52 minutes per visit.

Previously, the website offered live coverage of the sixth and 12th holes, but only during practice rounds.

2007

Wireless internet was introduced to the press building, ordinarily a welcome development for writers. But it malfunctioned during the first round on Thursday. Golf World’s timeline the next day read:

“Workers finish the overnight task of installing more than 300 DSL lines in the press room. The previous day the press room’s wireless Internet access went on the fritz, leaving scribes from around the world scrambling to file stories on deadline.”

Only Augusta National would attempt and succeed having every seat in a large media building hard-wired for Internet overnight.

Andrew Redington

The Masters Par 3 contest, once limited to in-person spectators, was opened to television audiences under chairman Hootie Johnson.

2008

ESPN took over from USA Network in providing Thursday and Friday television coverage, as well as the Par 3 Contest on Wednesday.

Masters.org, meanwhile, added “15 & 16 Live,” website coverage of the 15th and 16th holes to go along with “Amen Corner Live.”

2009

A Masters iPhone app was introduced, featuring live streaming.

AFP

Woods’ press conference at the 2010 Masters, his first session with reporters since his sex scandal, was broadcast live on multiple networks.

2010

At 2 p.m. on April 5, Tiger Woods strode into the interview room in the press center at Augusta National for his first news conference post-scandal. Among those televising the news conference live were ESPN Golf Channel,, CNN, Fox News Channel and MSNBC, as well as live-streamed on the Internet.

Woods’ first round of competitive golf following his off-course scandal attracted an estimated 4.94 million viewers on ESPN, the largest golf audience ever on cable, eclipsing the previous record of 4.8 million viewers for the 2008 U.S. Open playoff between Woods and Rocco Mediate on ESPN.

Related: New Tiger Woods book paints a complex picture

2011

Augusta National’s latest offering in technology was an iPad app, $1.99 in Apple’s App Store, “basically a scaled-down version of its website, Masters.com, with one notable exception: The iPad app will feature the ESPN (Thursday and Friday) and CBS (Saturday and Sunday) telecasts. We think,” Golf Digest wrote.

“The app itself shows in its Live Channels lineup ‘TV Broadcast’ each day of the tournament. The App Store says ‘Saturday and Sunday’s live CBS simulcast,’ and does not mention the Thursday and Friday broadcasts on ESPN.”

2013

The Masters continued to improve its website and apps, to the point that a television was not necessary to know precisely what was happening. New York Times media columnist David Carr noted this, writing, “The Masters app, which let me omnisciently check the leader board, scan for my own highlights and toggle between specific groups or holes, sucked me in. I barely looked up at the television … as I programmed my version of the Masters. There I was, staring at the device on my lap, looking at a bright future—no cable, no commercials, no bundle required.”

Keeping with the tournament’s desire to endlessly innovate, the Masters’ digital assortment of apps and live streams have become excellent ways to follow the tournament.

2016

The Masters became the first live event broadcast in the U.S. in 4K Ultra High Definition. “It’ll be golf’s biggest show, the 2016 Masters Tournament,” Wired.com’s Tim Moynihan wrote. “And because 4K content involves a wider color gamut in addition to all those extra pixels, the winner’s jacket will never look so green or so sharp. You’ll likely be able to see crumbs from pimento cheese sandwiches on faces deep in the crowd.”

High-definition cameras were first used on a limited bases in 2001. By 2007, it had 100 percent HD coverage of the course.

Televising in 4K Ultra High-Def was another technological leap forward for a club that otherwise has a reputation for stubbornly clinging to tradition.

2018

Augusta National will continue to confound us in various ways, as it has done in the past. One such example were its website choices of featured groups in 2013. Neither of the two featured groups in the first round featured Tiger Woods. One offered Peter Hanson, Charl Schwartzel and Webb Simpson, the other K.J. Choi, Zach Johnson and Graeme McDowell.

But its quirks notwithstanding, the Masters again will be televised to more than 200 countries and territories, which, depending on who’s counting, is pretty much all of them. And another 350 journalists from around the world will fill every seat in the new Press Building, all in the name of fulfilling Bobby Jones’ notion, that there must be someone to spread the news.