Ben Stansall/AFP via Getty Images

All sports, as we all know, are inherently trivial. And yet, so important. The games we play elevate the routine of day-to-day life, providing fun and laughter and, especially when done really well, pleasure almost beyond measure for participants and spectators alike.

The Olympic Games qualify under that elite heading. So does football’s World Cup. And so, in only a slightly less significant way, does the Ryder Cup. More even than the major championships, the biennial contest between Europe and the United States takes the game born in Scotland into the hearts and minds of those who elsewhere go about their business blissfully ignorant of all things golf.

“I was known in Denmark before I made the 1997 team,” says Thomas Bjorn, the first Dane to play Ryder Cup golf. “But I was definitely recognised more afterwards. That Ryder Cup changed the perception of golf in Denmark for a long time. Me being there made a big difference. And my profile changed. I represented something much bigger than before. It was a bit like making an Olympic team. I’m not sure the Ryder Cup is quite on that level — although it depends on the country — but people who have competed in the Olympics are looked at differently. The Ryder Cup is the same in that respect.”

Given that sort of transcendence, the Ryder Cup is a powerful beast, one capable of great things. Certainly, it has the ability to transport those who have played, particularly those from Europe, into worlds far beyond their previous depths of near anonymity. Many are those who have gravitated to an otherwise unimaginably heady public profile, one beyond the ken of just about anyone blessed with an esoteric talent for hitting small balls around fields with sticks.

Perhaps the most blessed example of this phenomena is Paul McGinley. The now 56-year-old Irishman was a steady player on what was then the European Tour. The winner of four events, McGinley peaked at 18 in the world ranking and played three times — on winning teams — in the Ryder Cup. So he was known well enough in golf circles.

Paul McGinley won the Ryder Cup as a captain and a player, shown here on the 18th green of the 2002 Ryder Cup, defeating Jim Furyk in singles. Adrian Dennis

But here’s the thing. In 2002 on the 18th green at The Belfry, McGinley holed the winning putt in the Ryder Cup. Cue a jump in his wider appeal. Then, in 2014, the Dubliner oversaw Europe’s stunningly comprehensive victory over the Americans while changing the way in which the captaincy was both perceived and executed. Suddenly, McGinley was properly famous and in demand. Today, his voice and face are well known on both sides of the Atlantic through his work with Sky Sports and Golf Channel. Largely because of the Ryder Cup.

“My public profile went up when I holed the winning putt in 2002,” McGinley says. “But it went to another level after my captaincy. It was a two-year window on the front line. Television came my way. I was invited to sit in the Royal Box at Wimbledon. [Former manager] Arsene Wenger had me speak to the Arsenal football team squad. I spoke to the Irish rugby team. I was invited to one of Google’s big conferences. Facebook, too, had me in their offices in Dublin. Adidas took me over to Munich. A new tangent opened up for me, all because of the Ryder Cup captaincy.

“I had a profile brands wanted to be associated with,” he continues. “The biggest thing is my relationship with the London Business School. They wanted to do a case study on me from a leadership point of view. I did that, and they made me an executive fellow. I’m the only sportsman to have that title. I go and answer questions on the case study. People from all around the world discuss it. That is humbling and great from a credibility point of view.”

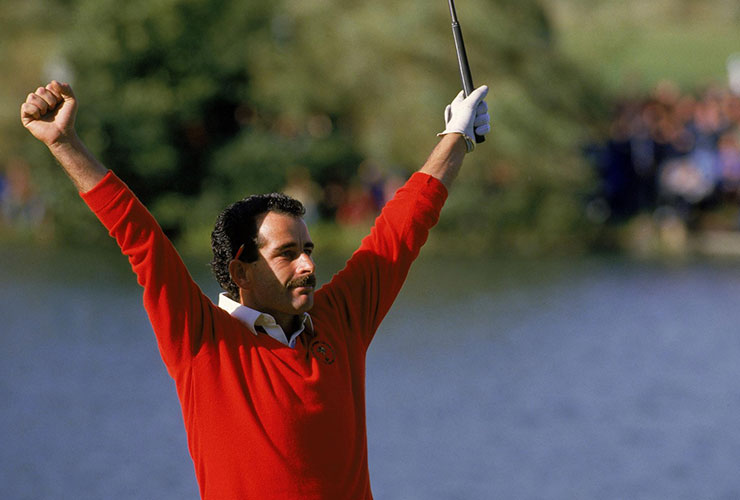

While he might be the best example of just how much a Ryder Cup connection can do for an individual, McGinley is far from alone. Take Sam Torrance, whose playing career certainly supersedes that of the Irishman, but whose elevation from mere golfer to national hero followed a similar path. The Scot features in one of the Ryder Cup’s most iconic images, that of the moment after he holed the winning putt at The Belfry in 1985.

“I did notice a difference after I holed that putt,” says Torrance, who captained the 2002 European squad to victory, again at The Belfry. “I always knew when people recognised me. You do, don’t you? But it never bothered me. What would upset me is if people stop asking me about it all. They still haven’t, thank goodness. I love all that. So it did me no harm. I’ve not had a bad career, but there is no doubt I am better known outside golf because of the Ryder Cup. It’s such a powerful thing. I take great pride in it all.”

Sam Torrance celebrates after holing the putt on 18 to secure victory in the Ryder Cup at The Belfry in England. Simon Bruty

Still, there is more to this enduring phenomenon than merely being lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time to hit what turns out to be the Cup-clinching shot. Merely playing in the Ryder Cup is enough to boost profiles and provide interesting opportunities that would surely never have come the way of those involved.

David Howell, a member of the European teams of 2004 and 2006, paid the apparently traditional visit to Wimbledon. But much to the five-time European Tour winner’s glee, he was also invited to turn on the Christmas lights in his hometown of Swindon. And there is one other special moment he recalls with pride.

“One week after the 2004 Ryder Cup we played an event at Woburn,” says the Englishman. “I was on the tee waiting to play in the pro-am when Soren Kjeldsen walked up. He got down on his knees and bowed to me. It was done in jest, but it was still a nice tribute. And on a weekly basis I was also treated differently by sponsors and promoters, which was nice and not just financially. When I arrived at the airport I was more likely to have a courtesy car waiting for me. I was part of a higher echelon we all wanted to get to. And the way I was treated was confirmation I was there.”

Where a player hails from can also have an effect on post-Ryder life, both on tour and off. Like Bjorn in Denmark, Nicolas Colsaerts was the first Belgian to play against the Americans, at Medinah in 2012. Suddenly, in a nation where football and cycling provide the biggest games and names, the now 40-year-old made golf a spot on the sporting map. And that Colsaerts performed so remarkably in one match only enhanced that feel-good factor.

“I played quite well and left a mark on the competition,” says Colsaerts, referencing the fourball match in which he partnered Lee Westwood to a last-green victory over Tiger Woods and Steve Stricker. “We are more than 10 years on from Medinah, but still people come up to me and talk about that round [Colsaerts shot an approximate 62, Westwood’s score counting at only one hole]. It’s incredible. It’s flattering. And it’s an honour to have touched people’s lives like that.”

Nicolas Colsaerts celebrates a birdie putt on the 17th green as Tiger Woods looks on during the Saturday four-ball matches for 2012 Ryder Cup at Medinah outside Chicago. Mike Ehrmann

Ah, but there was more. Colsaerts contribution to the European cause was noticed in high places.

“I did get two telegrams from the Royal family that year,” he says. “One when I won the World Match Play Championship in Spain. Then another after the Ryder Cup. Only four months apart. It was pretty cool. I was also honoured and flattered to be invited to speak to the Scottish PGA members at their Christmas lunch. A guy from Belgium. In my second language. I was really honoured by that. It was a cool recognition.”

Amid all of this positivity, it should be noted too, that Ryder Cup participation can have the odd unintended consequence. Ollie Wilson played under Nick Faldo’s losing captaincy in 2008 at Valhalla, an experience he still describes as “the highlight of my career.” But it did lead him to take a wrong turn.

The Ryder Cup was the greatest experience of Ollie Wilson’s career, but he admitted that it made him manage his career differently afterward, which is not something that worked out well for him. Andy Lyons

“What playing in the Ryder Cup did do was pose some questions that turned out to derail my career,” Wilson says. “I enjoyed the experience so much I was desperate to play more. So I made the decision to try and qualify next time, which meant I turned down the PGA Tour card I had earned. That is still the worst decision I’ve ever made in my career. I thought my best opportunity to play another Ryder Cup was to concentrate on Europe. Most of the best European players were competing in America. So I thought it would be easier to make the team from Europe.

“Then I got ill and started playing poorly,” he continues. “So that opportunity was gone. I thought I was invincible and could get the PGA Tour card a year later. But that never happened. And what did was a direct consequence of playing in Europe. I’ll never know what would have happened had I gone to the States, but the Ryder Cup was what pushed me into doing what I did.”

Speaking of which, what happens to individual players after their Ryder Cup debuts is much influenced by whether they played on a winning team. Needless to say, being part of a losing side tends to mean less to the public going forward. Andy Sullivan was a member of captain Darren Clarke’s team at Hazeltine in 2016, a year when the Europeans finished second.

“My public profile did go up incredibly,” Sullivan says. “But not for that long. Yes, everyone knew I used to work in Asda. And yes, I was invited to sit in the Royal Box at Wimbledon. But there is no doubt that it helps to have played on a winning team. Look at how Jamie’s profile rocketed when he won the winning point.”

The Jamie to which Sullivan refers is Donaldson. In 2014 at Gleneagles the now 47-year-old Welshman stiffed his approach to the 15th green to beat Keegan Bradley in Sunday singles and clinch the Cup for Europe. A plaque now marks the spot where that shot was struck.

“It is more than fair to say my name and likeness provoked a bit more recognition after the Ryder Cup than it did before,” says Donaldson, a three-time winner on the European Tour. “If only because hardly anyone knew who I was beforehand. The number of interview requests went way up. I was invited to all sorts of things. I was more in the public eye and loved every minute of it. It was fantastic, to be honest. Hitting that shot to clinch the Cup was the ultimate high. Going in I just wanted to be on the winning team. So to be lucky enough to be in that position was a huge bonus. You can’t make up that sort of scenario can you?”

No, you can’t. The Ryder Cup. Truly, it’s a wonderful thing.