By Daniel Rapaport

He couldn’t mourn forever. Not even for his father, the man who nudged him toward the sport he’d conquer. Eventually, Tiger Woods was going to have to play a golf tournament without being able to talk to his pop, his rock, afterwards.

Earl Woods died on May 3, 2006. He was 74 and his health had long been deteriorating. First diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1998, one year after his son took the sports universe much less the golf world by the throat, Earl won the first round. But as is so often the case with cancer, it wasn’t a one-round battle. It returned in 2004, and Earl fought like hell, but his fate was clear by April 2006, when he was too weak to come to Augusta National and watch his son at the Masters. Tiger tied for third, which was bitterly disappointing for two reasons—one, he was that good then. Anytime he wasn’t holding the trophy on Sunday evening was a loss. And two, he knew there wasn’t much time left. He wanted to give Dad one more triumph to savour.

“I had a chance, and I messed that up,” Woods says. “I knew that was going to be the last event that my dad was ever going to watch me play. He died not too long after that.”

Twenty-four days, to be exact. A heart attack struck the final blow. Tiger, by all accounts, was crushed. His guiding light had flickered out. “My dad was my best friend and greatest role model, and I will miss him deeply,” read the first line of his statement. But there was nothing he could say to convey what he’d lost.

In both 2004 and 2005, Woods played three events between the Masters and the U.S. Open—the Wachovia Championship, the Byron Nelson and the Memorial. In 2006, he skipped them all. So Woods arrived at the 2006 U.S. Open at Winged Foot Golf Club as something of an unknown. He was still the Vegas favourite, of course, but he hadn’t played a tournament in two months. And, we now know, he hadn’t really practiced, either.

“I wasn’t prepared to play that particular week,” Woods says. “I hadn’t practiced, I hadn’t done much. I tried to come up here and play.”

In its 99-year history, Winged Foot has never cared about how hard someone is trying. You can fake it around some courses. Not this one. It tests every facet of your game, every round. If you’re not dialled in, it’s going to show. If you don’t give it your full attention, it’s going to show. And even if your game is sharp and your mind present, you still might fail miserably. Forgiving, it is not.

After one hole of that U.S. Open, you sensed something might be off. Woods left an eight-footer for par well short, doubly strange because that was the era when he jammed putts into the back of the cup. Another shortish par putt on the second hole, another one left short. On the third, he three-putted from 45 feet. Three over through three. He played the next 15 in three over as well, and after an opening-round 76, there was a real possibility he’d do the unthinkable: miss the cut at a major championship. At that point, Woods has only missed three cuts on the PGA Tour as a pro and none in a major.

A bogey on the eighth hole in Friday’s second round left Tiger Woods at 10 over for the tournament and on his way to his first missed cut in a major. STAN HONDA

Friday told a similar story. Woods started on the back nine and made two double bogeys in his first eight holes to drop to 10 over par. Tiger Woods, 30 years old and squarely in his prime, winning all around the world, was 10 over par through 26 holes. He salvaged things slightly over the next two hours, making one birdie and one bogey, and stood on the 17th tee with an outside chance to make the weekend. He needed to play his last two holes in one under to do it. He bogeyed them both. He missed the cut by three, his first trunk slam at a major as a professional.

It was hard to believe, an uncomfortable reminder that Woods is human, and humans have emotions. Phil Mickelson—who, as you may have heard, had a pretty good chance to win that tournament—was asked his thoughts on his greatest rival’s performance. “Surprised is the biggest word,” he said. Charles Howell III played a practice round with Woods on Monday and liked what he saw. If anyone could return from a two-month absence for the death of a father and win the hardest golf tournament in the world, it would’ve been Woods. “On Monday, he hit it really, really well, and he had that look to him,” Howell III said.

By Thursday, that look had disappeared.

Michael Campbell, the defending U.S. Open champion that year, played the first two rounds alongside Woods. “It was obvious from the first tee shot that Tiger just wasn’t there,” Campbell said. “His mind was somewhere else. He didn’t have the same aura or mental fortitude that was such a big part of him being who he is. There was no electricity. His energy levels were clearly down.

“He looked empty, and there was a lack of intensity. He was just playing as though he wasn’t even trying, although I have no doubt that he was.”

Put differently, Tiger wasn’t Tiger. He may have looked the same, and his clubs and balls may have been the same, but that was not Tiger Woods.

“Normally he is quite chatty with me,” Campbell said. “We had played together a few times before that week. But he never said a word for 36 holes. Not one word in two days.”

Woods, of course, refused to blame anyone or anything besides himself. “I’m more frustrated than anything,” he said at the time. “It’s playing really hard. Marginal shots are going to get killed now. It’s the nature of this course.”

As anyone who’s lost someone will tell you, it gets better. It takes time, and each person heals differently, but it does get better. But doing that thing for the first time without them can be excruciatingly difficult. For someone who shared walks on the beach with their mother, the notion of doing it without her can be soul-crushing. If someone played poker with their grandfather every Sunday, it’s totally normal to feel physical pain when Sunday rolls around.

For Woods, that thing was golf. It’s what they shared. Earl was his first coach. The one who brought him to his first lesson with Butch Harmon in 1993. The one he bear-hugged so famously just off the 18th green at Augusta, right after winning his first major. Fourteen years later, golf is still a huge part of Woods’ life. Tiger has a family of his own now—his first child, Sam, was born 13 months after Earl died—and family has replaced golf as the most important thing in his life. But golf is still there.

And so is Earl.

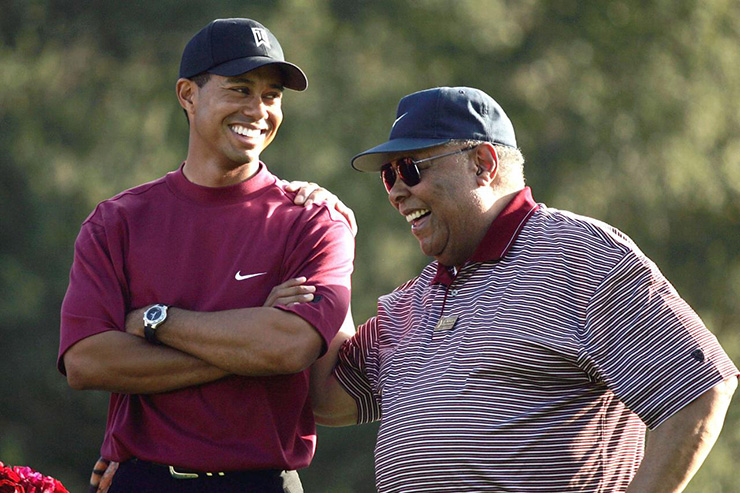

Tiger smiles as he stands with his father, Earl, at the 2004 Target World Challenge. Doug Benc

“I wish I had Dad around now,” he says. “There’s not a day since Dad passed that I haven’t thought about him. He’s part of my life, and I was very fortunate to have him a part of my life for as long as I did.”

Woods knew that Dad would have wanted him to keep playing. To keep grinding. To keep using his supreme physical talents and extraordinary mental fortitude to keep on winning. And that’s exactly what Tiger did. He took another two weeks off after Winged Foot—“more grieving”—then finished tied for second at the Cialis Western Open. From there it was on to the Open Championship. He arrived at Royal Liverpool in July, clearheaded and determined.

“I had Dad as my 15th club at Liverpool,” Woods says. “I felt a certain calm, a certain ease that I hadn’t felt in a while. Dad was there right next to me.”

Woods resisted the temptation to try to fly Hoylake’s redone bunkers and hit just one driver the entire week on the baked-out course. Earl would have beamed at that restraint.

“This has been a masterclass of tactitional golf,” Nick Faldo said on the broadcast. “It’s been really fantastic to watch.”

When Woods holed his final putt to seal a two-shot victory, the stoic champion turned into a sad kid who missed his dad. He cried. Wept, into caddie Stevie Williams’ shoulder. Never before had Woods showed that kind of vulnerability on the golf course. You knew he was thinking of one person and one person only.

“Dad was there right next to me.”

An emotional Tiger Woods walks with his caddie Steve Williams after winning the 2006 Open Championship at Hoylake a little more than two months after his father’s death. STRINGER

After Hoylake, Woods played six more stroke-play events in 2006. He won the first five, including the PGA Championship for major No. 12, and finished second in the last one. One of the greatest stretches in golf history.

Woods returns to Winged Foot this week for another U.S. Open. Things couldn’t be more different than 14 years ago. He’s no longer the undisputed best player in the world. (According to the World Rankings, he’s No. 21). He had no kids then. He has a daughter and a son now. He was an emotional wreck then. He seems genuinely happy now.

Tiger might win this tournament, or he might miss the cut. But maybe the focus shouldn’t be so much on how he plays this week. If 2006 is any indication, Tiger Woods is not to be defined by what happens at Winged Foot. It’s about what happens after.