Gregory Shamus

By Joel Beall

MAMARONECK, N.Y.—He told us a revolution was coming, which we ignored. He told us how it would come and we laughed. His trials were met with schadenfreude, his earnestness misinterpreted as arrogance, and when his methods began to work, we said they wouldn’t when and where they would matter most.

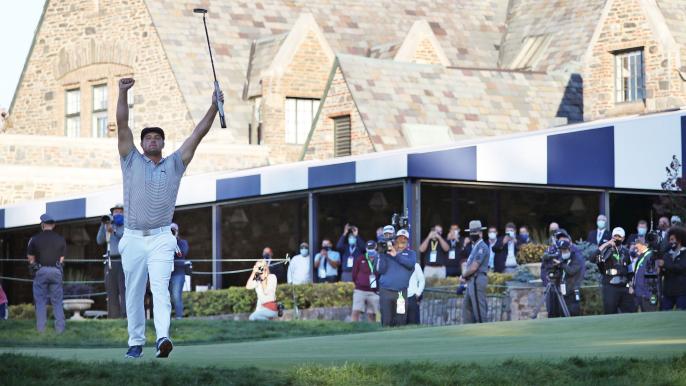

But now there is proof, finalised on a hole aptly named “Revelations.” The Mad Scientist proved his formula right and his doubters wrong (and perhaps converted many along the way), and for that Bryson DeChambeau was crowned United States Open champ.

“I did it. I did it,” DeChambeau said Sunday night. “As difficult as this golf course was presented, I played it beautifully … It definitely is validating that I’m able to execute time and time again and have it be good enough to win an Open.”

We tend to view U.S. Opens, especially those conducted at Winged Foot, as prize fights, decided by who is left standing. In a sense that is true, as DeChambeau was the only player to finish under par out of the 144-player field this week. But the recently-turned 27-year-old dished out his share of heat, shooting in the 60s three of four rounds—highlighted by a final-round three-under 67—and never finishing over par to win by a whopping six shots.

“Surreal. It sounds amazing, but surreal,” DeChambeau repeated. “It’s been a lot of hard work.”

Much was made of DeChambeau wailing driver after driver into the dark on Saturday evening, so deep into the night that the Winged Foot grounds crew turned on flood lights so he could chase a demon only he could see. In truth, Bryson does that most tournaments, no matter his standing. He is his generation’s Vijay Singh, working the range at such odd and long hours the maintenance staff is best to leave him a key. Bryson’s display Saturday night was just that—a Saturday night.

However, what was noticeable was DeChambeau’s walk from the range to the first tee Sunday afternoon. He can be a bit twitchy, DeChambeau, forever looking like the kid told not to run by the pool. That Bryson was gone, replaced with a confident and collected prowl that would do Dustin Johnson proud. This was no show; he knew.

Of course, Winged Foot has made a reputation off those who stood at its first filled with conviction. It was already breaking score cards and souls in Round 4 with tucked pins and ever-hardening greens kissed by incessant crosswinds. This was the day, many asserted, the beast would show its teeth.

For posterity, this was mostly true, just one player breaking par on Sunday as the field average hovered at five over. Bryson, as he’s tended to be in his career, was the outlier. He showed that strut ran deep, finding the fairway off his opening drive in howling in-your-face breeze. DeChambeau began the day with three pars, adding a birdie at the fourth after running up his approach from the deep rough. With Wolff taking a bogey at the third, DeChambeau’s two-shot deficit heading into the day was erased.

Gregory Shamus

A poor drive at the fifth left a mean up-and-down for Wolff, one he failed to convert. Bryson, now up one. The two traded pars and a bogey over the next three, and at the 556-yard par-5 ninth both men found the green in two. (For those scoring at home, Bryson went driver, wedge). It was here that Bryson’s putter, a tool that was much-maligned when he first arrived on tour but has turned into a weapon, delivered as DeChambeau rolled in an eagle from 40 feet.

“I’ve become a great putter, and my ball-striking has improved consistently, and now I’ve got an advantage with this length, and that’s all she wrote,” DeChambeau said.

Not to be outdown, Wolff followed suit from 10 feet. Game, on.

Or so we thought. Wolff left his tee-shot on the 198-yard par-3 short and could not save par. Bryson watched it unfold with a sensible lag. Lead to two, then to three at the 11th off a 320-yard drive and a pitch to 13 feet, which DeChambeau dutifully cleaned up. Wolff tried to press; alas, he is just 21 years old, in his first U.S. Open. Impressive as his performance was over 63 holes, it was clear he was holding on for dear life. On this afternoon, the bull won, tossing Wolff off at the 14th, another wild drive bestowing a scramble opportunity that wasn’t to be. It was here the ref called the match, as Bryson sunk a sidewinding 10-footer to save par.

“That was huge,” DeChambeau said. “Just hit it off the top of the face, came out dead and rolled down there to ten feet, and I made it. That was huge. If I don’t make that and he makes his, you know, we’ve got a fight.”

The victory march was on, with a double by Wolff at the 16th officially confirming the inevitable.

Now, someone was going to win this tournament (at least, we think; 2020 has been an odd year). That it’s a player who entered the week ranked 9th in the world is not necessarily surprising. But we thought the player who won would have done so in certain terms. Winged Foot was supposed to be the antidote to courses coming out on the business end of the distance boom. The victor would be one of precision who played with subservience. That is how Geoff Ogilvy and Fuzzy Zoeller and Hale Irwin and Billy Casper and Bobby Jones had done so, so that’s how it would be done.

Instead, Bryson never wavered. Make no mistake, his touch around the greens was superb (gaining five strokes on the field in this area), but it was the tee-to-green came that delivered this championship to Bryson, ranking third in both sg/off-the-tee and sg/approach. He did so by hitting a total of nine fairways over the weekend, muscling his way out of trouble when he found it, which was often. That’s supposed to be an impossibility here, and given he was the only player who finished in red, that’s not false. His quest for power paid off.

“I mean, it was a tremendous advantage this week,” DeChambeau said. “I kept telling everybody it’s an advantage to hit it farther. It’s an advantage.”

But with Bryson DeChambeau, it’s never been about his quest. It’s how his quest is conceptualized, executed, achieved. Those prisms should give greater appreciation for the result. They often do the opposite.

Jamie Squire

DeChambeau has been different from Day 1. He wears a Hogan cap and names his clubs. He writes his signature backwards with his opposite hand. He grew up reading “The Golfing Machine” and “Vector Putting” and brought single-length irons out of the shadows. His physical transformation was the latest of eccentricities. Last fall DeChambeau announced an ambiguous overhaul in pursuit of more distance and did just that, turning from man into Mack Truck while gaining over 20 yards off the tee.

There is nothing standard about this cat in a sport whose players tend to be of the cookie-cutter variety. One would think a bit of color in a sea of vanilla would be welcomed; instead, Bryson has been marginalized for standing out.

“There’s always going to be people that say things. There’s always going to be people that do things,” DeChambeau said. “But no matter what, my focus and my message to everybody out there is each and every day that you’re living life try and make this day better than the previous day.

Some of the ridicule is self-inflicted. DeChambeau tangentially compared himself to George Washington and Albert Einstein before earning a tour card. He had a melodramatic outburst at Carnoustie’s range during the 2018 Open. He tried to confront Brooks Koepka when Koepka criticized his slow play and has been needled by Koepka ever since. There were run-ins with the USGA and rules officials and fire ants. They are not so much controversies as they are oddities . . . but there sure seemed to be a lot of oddities.

However, most of the Bryson backlash stems from two incontrovertible truths. The first is his audacity in a game where conservatism reins, and on that front, expect the tension to endure. But the second, and perhaps more substantial, piece: DeChambeau was advocating a new way without achieving anything of substance. Yes, he was a U.S. Amateur and NCAA champion with six tour wins. Conversely, golf judges its stars by one category and one category only, and until DeChambeau captured a major, his words and actions and ideas were nothing more than a breathless sales pitch. At Winged Foot, DeChambeau delivered to his critics his most resounding response yet.

“My goal in playing golf and playing this game is to try and figure it out,” DeChambeau said. “I’m just trying to figure out this very complex, multivariable game, and multidimensional game. It’s very, very difficult. It’s a fun journey for me. I hope that inspires people to say, hey, look, maybe there’s a different way to do it.”

What DeChambeau has done, how he has done it and where the game goes from here—Bryson said he’s moving to a 48-inch driver that could rain 370-yard drives—well, that is a matter for a different day. This day belongs to the revolution and the man who brought it.