Bettmann

By Dave Shedloski

When Tiger Woods returned to the Masters in 2018 after a two-year absence because of chronic back problems, expectations for him still were remarkably high to the point that he had to interject in his pre-tournament interview, “I have four rounds to play, so let’s just slow down a bit.”

He was responding to a question that began, “Some people are saying that if you were to go on and win here this week, it would rank as the greatest sporting comeback of all time.”

Tiger wasn’t biting. He could smell the hyperbole from the podium. Plus, he knows his golf history. So his response was definitive and dutifully respectful to a man who returned from a near-fatal automobile accident to win six of his nine career major championships, including the triple crown in 1953. He knows the story of Ben Hogan.

“I think that one of the greatest comebacks in all of sport is the gentleman who won here, Mr. Hogan,” Woods said. “I mean, he got hit by a bus and came back and won major championships. The pain he had to endure, the things he had to do just to play, the wrapping of the legs, all the hot tubs and just … how hard it was for him to walk period. … That’s one of the greatest comebacks there is, and it happens to be in our sport.”

Woods understood that he hadn’t walked in Hogan’s shoes. But now, sadly, scarily, he faces a comeback equally daunting—or perhaps even more so—after suffering severe leg injuries in a one-car accident Tuesday in California. That Woods survived the horrific crash is something of a miracle, but then, the same could be said for Hogan.

It happened in the early morning hours of Feb. 2, 1949, Groundhog Day. On a fog-shrouded, ice-covered road 37 miles west of Van Horn, Texas, a Greyhound bus collided head-on with a recently purchased black Cadillac sedan carrying the sinewy Texan and his wife, Valerie. The couple was returning home to Fort Worth from Phoenix, where Hogan had lost a playoff to fellow Texan Jimmy Demaret. Indisputably, he was the top player in the game, having already won twice in January after a 10-win season in 1948 that included the money title and Vardon Trophy. In all, he had collected 37 titles since the end of World War II.

Because he had just begun to cross a small bridge on Highway 80, Hogan had no room to avert the oncoming 20,000-pound bus, which had just passed a truck and still was occupying the eastbound lane. Driving an estimated 25 mph because of the fog and ice, Hogan jerked the car as far to the right as he could and then dove across the body of his wife as the bus barreled down on them at close to 50 mph. That gesture of gallantry turned out to be a life-saving move for both of them.

Valerie, who was protected by her husband from being ejected through the front windshield, sustained minor injuries. But Ben, the reigning U.S. Open and PGA champion, was hurt severely. He suffered a broken left ankle, contusions to his left leg, a broken collarbone, a cracked rib, a double fracture of the pelvis, a head abrasion and internal injuries. Even so, he escaped certain death, as the engine of his car had pushed into the steering column, which in turn was propelled through the driver’s seat.

It took an hour to extricate Hogan from the wreckage and 90 minutes before an ambulance arrived. In the confusion, no one had immediately called for assistance. “Ben couldn’t understand why no one was coming to help us,” Valerie said later. He complained most about the pain in his mangled left leg.

Initially, doctors weren’t certain Hogan would survive, and if he did, they couldn’t be sure he’d ever walk again. Returning to top-tier competitive golf seemed like an impossibility for the 1948 “Golfer of the Year,” the first man since Gene Sarazen in 1922 to win the national open and PGA Championship in the same year.

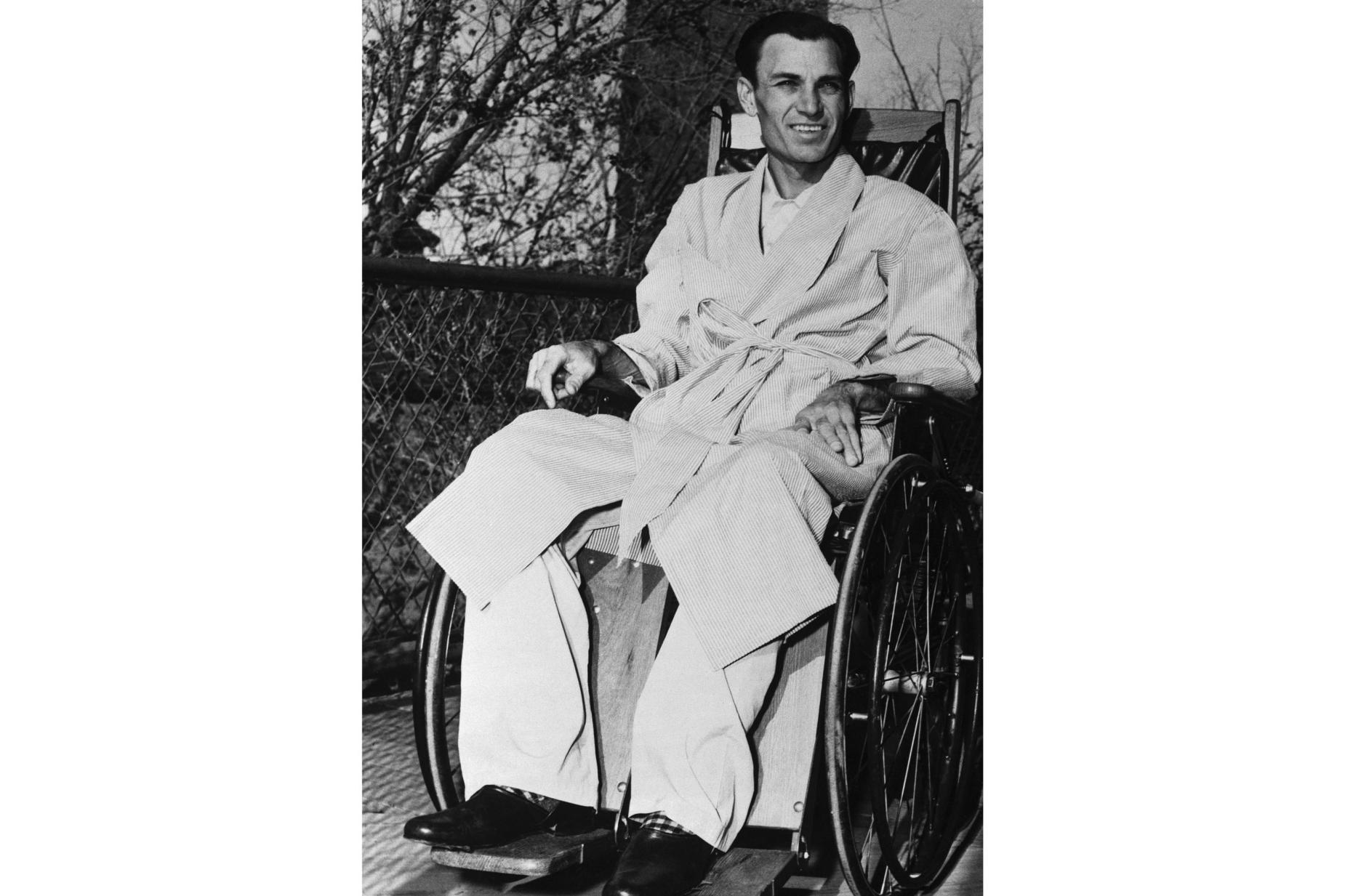

Ben Hogan spent 59 days in an El Paso hospital after the accident before returning to his home, surviving a scare a month into his recovery when a blood clot travelled to his lung.

(Photo: Bettmann)

He spent 59 days in an El Paso hospital, but a month into his stay, Hogan took a turn for the worse when blood clots began to form in his left leg and one broke off and invaded his right lung. Despite his doctors’ best efforts, more clots formed, and Hogan’s condition became grave.

A specialist from Tulane University in New Orleans, Dr. Alton Ochsner, was brought in, and he didn’t waste time. During a two-hour procedure, the vascular surgeon tied off the vena cava, the main vein that delivers blood from the lower extremities to the heart. Because of that, Hogan would endure severe pain and circulatory problems in his legs the rest of his life. He wrapped them in ace bandages every day, and he soaked them in hot water and Epsom salt after every round. Just as Tiger had said.

Though he didn’t have the benefit of the medical advances available today to Woods, Hogan was only 36 years old at the time, physically fit and without a history of injuries. Woods is 45, only months removed from his fifth back surgery and has undergone numerous surgeries on his right knee, the leg most severely damaged in the rollover crash.

Hogan arrived home on April 1, and as ambulance attendants carried him to the front door of his home, Valerie said, “I want you to see the redbuds in the yard. See them?”

“I see them. They’re wonderful,” he replied, smiling. “It’s great to be back.”

In May, Hogan was back on a golf course, but only as a spectator at Dallas Athletic Club, where he watched Byron Nelson and other friends in the Texas PGA. He told reporters he was able to walk about three holes and feared that of all the injuries, his broken collarbone was the most worrisome. “It wasn’t broken in a place where it can grow back easily,” he said. “I wonder if it will ever permit me to swing a golf club right again.”

He improved well enough in the succeeding months to fulfill his duties as U.S. Ryder Cup captain at Ganton Golf Club in England in September and caused a minor kerfuffle by his decision to ensure his team was sufficiently fed by bringing with them nearly a ton of beef, ham and bacon. The Americans rallied in singles for a 7-5 victory.

Bettmann

Hogan was well enough to fulfill his duties as 1949 U.S. Ryder Cup captain, leading his team to victory at Ganton Golf Club in England.

It wasn’t until Saturday, Dec. 10 that Hogan was able to play his first 18 holes, touring Colonial Country Club with head pro Raymond Gafford. He did not reveal a score, but said only, “I didn’t hit them very well.”

Which made the events one month later truly astonishing. Returning to competitive golf at the Los Angeles Open at friendly Riviera Country Club, where he had won the U.S. Open (and where, coincidentally, Woods now hosts a PGA Tour event that ended two day before his accident), Hogan somehow played well enough to take the lead thanks to a final-round 69. But Sam Snead birdied his final two holes for a five-under 66 to tie Hogan at four-under 280.

His legs aching and weak, Hogan rued the thought of an 18-hole playoff, but he got a reprieve when heavy rains, which already had pushed the tournament into Tuesday, forced further postponement of the playoff by a week, to the following Wednesday. It didn’t matter. Snead emerged with the victory, shooting 72 to Hogan’s 76 and ruining a fairytale ending. But Hogan would go on to author a more incredible story a few months later by defeating Lloyd Mangrum and George Fazio in an 18-hole playoff to win the U.S. Open at Merion.

Bettmann

Sixteen months after the accident, Hogan held off Lloyd Mangrum and George Fazio in a three-way 18-hole playoff to win the U.S. Open, the first of six more majors he’d claim during the remainder of his career.

The “mechanical man,” as he was known in the press, was just 16 months removed from the accident, and he would add five more majors: two Masters, two more U.S. Open titles and the 1953 British Open at Carnoustie that completed his triple-crown season. He arrived home to a ticker-tape parade.

Because of his chronic leg problems, Hogan competed only sporadically after the accident. Thus, only 11 of his 64 career titles came after 1949, the last, fittingly, at the 1959 Colonial National Invitation in Fort Worth. Though still a phenomenal player, Hogan lamented that his game, “was not as good as before. I was better in 1948 and 1949 than I ever was.”

A postscript: The driver of the greyhound bus that struck the Hogan car was a man named Alvin H. Logan, who stood trial in Van Horn for aggravated assault for his role in the accident. Logan, 27, insisted that Hogan had crossed the median and was skidding sideways towards the bus preceding the collision. Investigators, however, determined that the bus was almost fully on the left side of the road at the moment of head-on impact. At the time of the trial, in mid-June, Logan already had left the Greyhound Bus Company following his involvement in another accident that resulted in one fatality. Logan was found guilty of the aggravated assault charge. He paid a fine of $25.