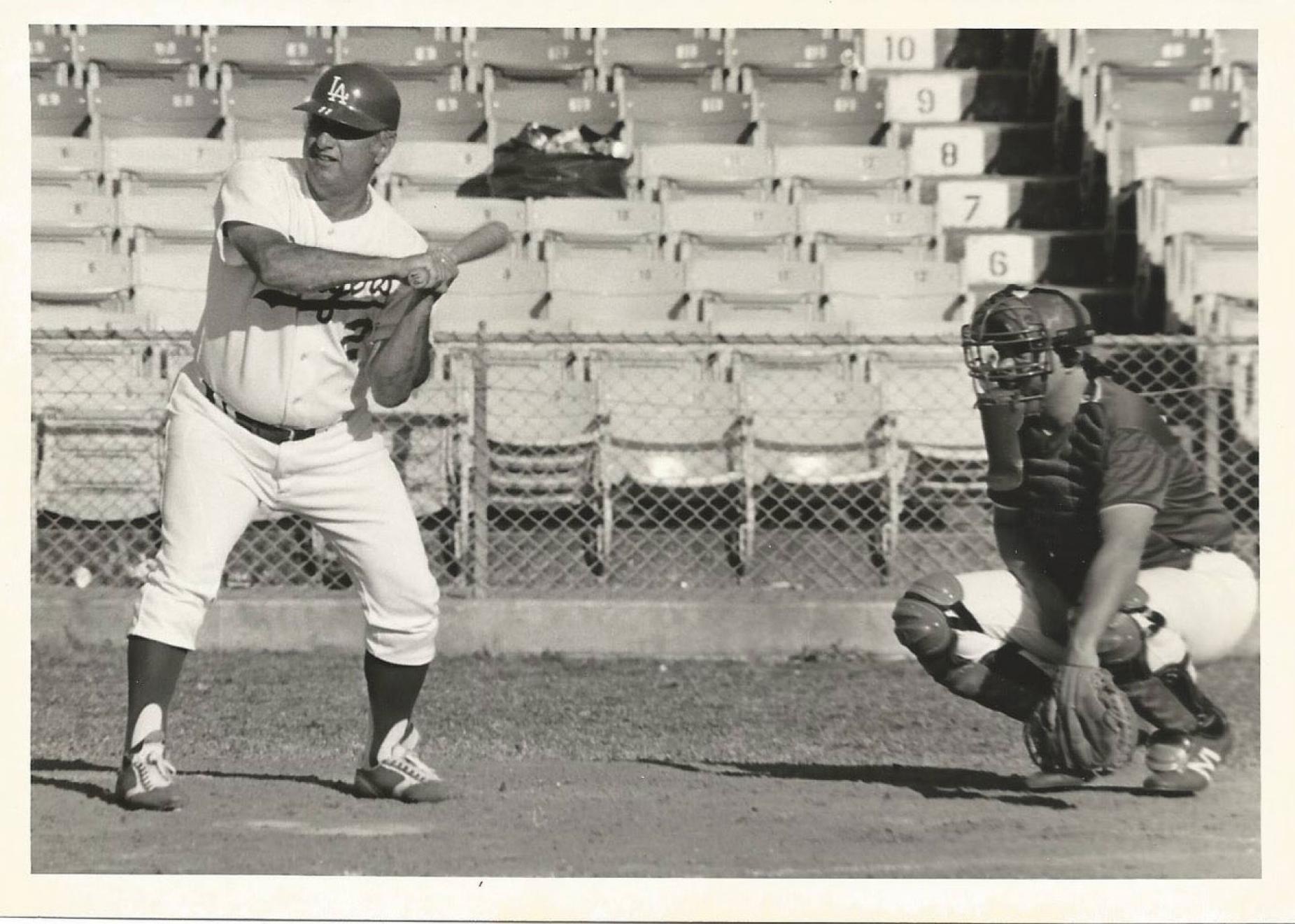

Our writer, John Strege, is catching as Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda bats during a staff vs. media game at Dodgertown in 1979.

By John Strege

Longevity has no particular value of its own, its currency instead gleaned from memories collected along the way. We do not remember days, a poet once wrote, we remember moments.

Of those culled from 51 years in sportswriting, most have less to do with outcomes of baseball games, championship fights, golf tournaments or other sporting events—however historical or epical—than with encounters peripherally related.

Playing recreational golf with Tiger Woods, for instance. With Kevin Costner. With Dinah Shore in a pro-am, a scramble, group hugs after every birdie. With one of the Righteous Brothers, who sent a handwritten note afterwards, signed, “Righteously, Bobby Hatfield.”

Hitting tennis balls with Arthur Ashe (“get it on the first bounce,” he said, admonishing me). Meeting, on the day after the 1988 Olympics, a young South Korean orphan girl my wife and I were sponsoring via Compassion International, an appreciably more memorable moment than Ben Johnson’s failed drug test.

Muhammad Ali, ever the showman, eager to show me how he levitates, in reality, a clever sleight of foot, in a storage room of a department store at which he was promoting a line of cologne, “the precursor, no doubt, to soap-on-a-rope-a-dope,” I wrote in a column for the Orange County Register.

Joey Bishop, Rat Pack member, Register subscriber and avid boxing fan, phoning on Mondays following championship fights to rehash them. We once discussed a book project. A teetotaler, Bishop already had the title: I Was a Mouse in the Rat Pack. He never did write the book. His stories about Sinatra alone would have sold it.

Knowing Vin Scully; playing tennis with Anne Koufax, Fran Cey and other wives on spring-training mornings at Dodgertown; sharing a couple of scotches with Dusty Baker in the back of the Dodgers’ plane while listening to him explaining the impact Henry Aaron had had on him.

Maybe best of all, for a kid growing up reading his columns in the Los Angeles Times, calling Jim Murray a friend.

I knew how to compute batting averages on a slide rule when I was 10, so no need now for a calculator to figure that 51 years equals more than half a century. Or that 51 is enough. A year ago, I made the decision to retire, and today is my final day (though I’ll still be turning up on GolfDigest.com at times).

Thirty-five of those years involved golf, the last 22-plus with Golf Digest and Golf World, the best golf publications and websites in the world.

My first income from the game involved an embarrassing misstep. For a brief time in the summer of 1968, I caddied at Hacienda Golf Club in La Habra Heights, Calif. The caddie gig was a moonlight job, though it occurred in the daylight. I was employed in the late afternoons/evenings as a busboy at a nearby restaurant.

One morning, I was assigned a loop in a tournament, the bag of the son of the great character actor Richard Jaeckel, one of the dozen in the highly acclaimed war film, “The Dirty Dozen.” Barry Jaeckel, I quickly learned, had just won the Southern California Amateur (and would eventually win on the PGA Tour and European Tour). Unbeknownst to me until after our 18 holes together, it was a 36-hole affair and I had tables to bus that afternoon.

I sheepishly explained that I had to leave. I preferred to slink away even without getting paid. Jaeckel, to his credit, paid me well. Given that I was making $1.40 an hour as a busboy, it would have been more lucrative had I worked the second 18.

Several months later, still a high school junior mentored by a teacher who cared (thank you, Don Chapman), I found my way into journalism, to the extent that writing prep roundups for the Whittier Daily News qualifies as journalism.

Strege hanging out with Vin Scully in 2015 and Dinah Shore during her tournament pro-am in the 1980s.

The first golf I covered was the 1976 U.S. Amateur at Bel-Air Country Club, for the Los Angeles Times. It was more memorable for its defending champion than its champion—Fred Ridley, now the Augusta National chairman, trumping Bill Sander, no disrespect intended for the latter.

In 1985, one of my first tournaments for the Register was the Uniden LPGA Invitational, Nancy Lopez the defending champion. To advance it, I arranged a phone interview with Lopez, who was exceptionally friendly, as advertised. At the end of our conversation, she signed off saying, “thank you, Jack.”

I was coming off six seasons on baseball, where I had been called far worse (looking at you, Tommy Lasorda), so I thought nothing of it. I was out when Lopez called back, leaving a message apologizing for calling me Jack. Instantly, she became my favourite golfer ever.

Meanwhile, it was my good fortune that in a small tract home in our circulation area, a prodigy was growing up. I began covering Tiger Woods in earnest when he was 14, and for the next six-plus years enjoyed a front-row seat, and at times a living-room seat, to the evolution of one of the most dominant athletes in sports history.

David Cannon

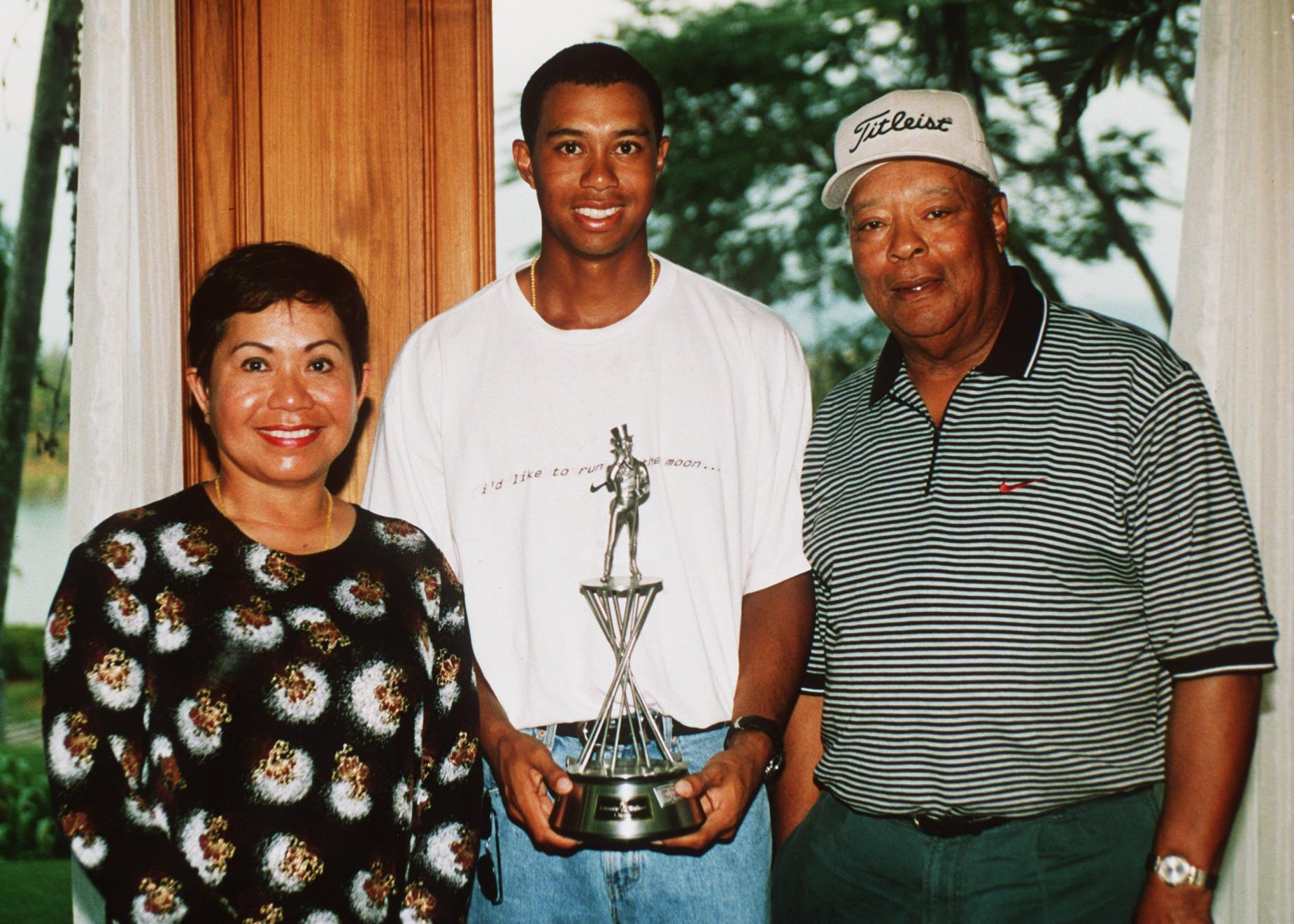

Our writer covered Tiger’s junior career in Southern California, spending many days with Woods and his parents Kultida and Earl.

Tiger’s parents Kultida and Earl were exceptionally gracious, even inviting my wife and me over for dinner once. Earl, with whom I played golf on several occasions, reliably helped fill my weekly golf column. Kultida often called just to chat, or to phone with a scoop, as she did when the NCAA briefly suspended Tiger, then a Stanford sophomore, for allowing Arnold Palmer to pay for his dinner when the King was playing a senior event in Napa.

I can’t say what, precisely, the pursuit of perfection looks like, though a few seasons watching Rod Carew in a batting cage must have been close. That thought occurred to me recalling visits to the Woods’ home to interview Tiger in advance of a U.S. Amateur, U.S. Open or Masters. When we were done, I’d usually hang around talking to Earl outside, and I could hear Tiger hitting chip shots in a living room full of trophies, some of them crystal and lining the carpet. To my knowledge, he never broke one.

In December 1995, a day after he returned home from Stanford following finals, we played golf together at Coto de Caza, along with Earl and Coto’s head pro at the time, Mike Mitzel. What stuck with me from this round was that Tiger had not hit a ball in the preceding two weeks because of finals, and that this was a recreational round with a chopper (me), yet he took every shot seriously, even personally, showing flashes of anger at poor ones. Maybe Rembrandt fumed over an errant flourish with the brush, too, though he could paint over his.

Three months later, I introduced Tiger to Costner. The backstory involves my brother David, an accomplished sports journalist and outdoors writer, who was a friend of Costner’s from their days as Delta Chi fraternity brothers at Cal State Fullerton. They often went fishing together, and in 1994, when Dave was headed to Atlanta to cover the Super Bowl, Costner was going, too, and invited Dave to fly there with him on his private jet.

One day, Dave called and asked if I would like to play golf with Costner and him and our Register colleague Rod Millie, and if I had any connections to set it up. This was post “Dances With Wolves” (though a couple of years before “Tin Cup”), when Costner’s celebrity was exploding. We preferred a private course to spare Costner the commotion his appearance might cause. I made a call and got us on Sherwood Country Club in Westlake Village.

Costner was new to golf, though he did hole a long putt early in the round. “Local knowledge,” he said. The man who played the lead in “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves,” Costner apparently was aware that two early Robin Hood movies had been filmed where the course was built, hence the club taking its name from Sherwood Forest.

Well played, Kevin.

Near the end of March ’96, I drove up to North Ranch Country Club in Westlake Village, where Stanford was competing in the Southwestern Intercollegiate. I was there to talk to Tiger about the Masters, his summer plans and whether those plans included turning pro. I virtually was certain they did, though he refused to give it up.

We were sitting on a curb by the putting green when I saw Costner approaching. He was there to watch USC golfer Brian Hull, whose mother worked for him. I stopped Costner to say hi, we chatted for a few minutes, then I introduced him to Tiger and they briefly talked.

Andy Lyons

Tiger Woods and actor Kevin Costner talk during the 1997 AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am.

“Skinny dude,” Tiger said when Costner was walking away.

Less than a year later, they were partners in the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am. Maybe they’d have found each other anyway, given their soaring popularity in their respective arenas, but I’ll cop to an assist for the introduction.

The point of all of this is that I’ve been blessed, a timid kid with more ambition than talent, grateful for the ride of a lifetime that followed. I’ll close with this, from the extraordinary German theologian and martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who said it better than I ever could.

“In ordinary life,” he wrote, “we hardly realise that we receive a great deal more than we give, and that it is only with gratitude that life becomes rich.”