“On 11 I looked. It’s the first time I really looked at a leaderboard, and I kind of chuckled and I said, ‘yeah, of course.’”

—Wyndham Clark, on seeing Scottie Scheffler’s name on the leaderboard

“Yeah, no surprise to see Scottie’s name up there.”

—Xander Schauffele

After two years and endless arguments, we finally have an answer to one of the big questions facing modern golf. Be it resolved: 72 holes is too long for a professional tournament.

This judgment is not about the PGA Tour, and it’s not about LIV. It’s about a pesky concept in sports called “sample size.” The greater the sample size, the less likely it is for underdogs or flukes or romantic notions harboured in our most far-fetched dreams to come through and thrill us with an unexpected result. In the void where such bracing narratives might have existed, reality makes way for the machine—the superior force, the superior arsenal, the unbending rule that we must regress to the mean of our core selves.

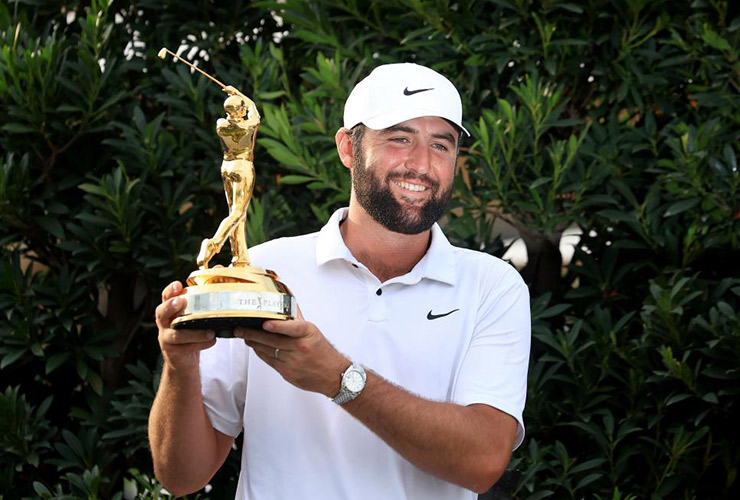

Enter the caveat: There is one player for whom 72 holes is just perfect. Enter your Players champion. Enter Scottie Scheffler.

Scottie Scheffler – Chris Condon

The parallels we can use to explain sample size range from the silly hypothetical (if you played one possession of basketball against LeBron James, you could beat him with an extremely lucky hook shot from 40 feet away, but if you played 100 possessions, he would erase you from existence) to the historical (the Confederate Army had superior generals and superior strategy and sensational victories but were ground to dust over time by the resources of the Union). In all cases, more time and more repetitions bring us closer and closer to the expected result until, with a large enough sample, the expected result starts to feel inevitable.

Which is all a fancy way of saying that if you spot him four rounds of competition, Scottie Scheffler starts to feel like pure, cold inevitability—the tide that rolls in and sweeps the detritus away.

Indulge a thought exercise: In one word, how would you describe his 64 on Sunday to erase a five-shot deficit and beat Wyndham Clark, Brian Harman and Xander Schauffele by a single stroke, capturing his second straight Players Championship? It was certainly spectacular, and dynamic, and awe-inspiring. It was also clinical, relentless, and somewhat normal. For the player who has not yet shot a round of par or worse in 27 tries this entire year, it wasn’t a matter of whether a 64 was coming; it was a matter of when. We didn’t see it in the first three rounds, which meant we had to see it Sunday. This is simple probability, and Scottie Scheffler is mathematical law.

The greenside bunker is not a problem for the defending champ.

Scottie Scheffler's birdie at 16 moves him back into a share of the lead @THEPLAYERS. pic.twitter.com/aEi7onLZPE

— PGA TOUR (@PGATOUR) March 17, 2024

Now, OK. Breathe.

Let’s come back to earth for a moment. Let’s clear our heads. Contrary to what we might feel just now, Scottie Scheffler doesn’t win every single tournament he plays. He doesn’t even win half of them. He is the No. 1 golfer in the world by a country mile, he’s beyond exceptional in every statistical category except putting (where he’s now, suddenly, very good), and he brings a quiet, almost plodding swagger that you could call intimidating, but he’s not quite immortal. He’s not prime Tiger Woods.

The point that’s worth making, though, is he’s starting to seem like it. This Players Championship, on the heels of his victory at Bay Hill a week ago, was one he wasn’t supposed to win. On Friday, it looked like he might withdraw with injury. He was never really in the mix on Saturday, just hanging around while Harman and Schauffele went low. This was his time to confirm his excellence with a top-10 finish and move on to the spring.

But he won it anyway. He won by a display of pure excellence that felt strangely ordinary except for one shot—the 92-yard hole-out for eagle on the fourth hole that started his victory march. From then on, it was the banality of perfect golf. The 64 could have been lower; he missed some putts. He could never lose. The prospect of Wyndham Clark making the putt on 18 was an illusion because Clark’s near comeback was a story of humanity grasping in turbulent waters. But you start to suspect, against reason, that Scheffler is the turbulence itself.

There’s an emerging narrative that Scottie Scheffler is boring. Early in the week, one reporter went around asking certain players what they thought of the idea that he didn’t have “star power” in the same way that Rory McIlroy or Jordan Spieth or Tiger Woods have it. In response, others posit a counter-narrative that he’s actually very interesting but purposely makes himself dull for the media as a way to live an easier life. I don’t think either is true—he’s more interesting and likeable than people give him credit for, even in press conferences, and no, he’s not some grand social strategist withholding his exciting inner self from a bloodthirsty press.

But he’s big, and he’s plainspoken, and his effect is calm even when he’s feeling nervous, and beneath it all is the undercurrent of outrageous excellence that is still, to some degree, taking us by surprise. We can’t stop looking at Rory, at Jordan, at the mercurial ones who should be living Scheffler’s life. His is a strange excellence. An excellence that’s elemental; this isn’t the electric individual casting himself against nature and defying the odds, but an inflexible imperative … the Russian snow burying the invading army.

His press conference after his victory was typical—at first, it seemed like he was speaking quickly to be done with it all and leave, with more or less rote responses, but then it segued into more genuine remarks, including a thoughtful answer about the act of performing in front of the media generally.

“I just think that I try to be as honest as I can,” he said. “This environment here where everything’s being recorded I think it can be a tough place to be a hundred percent honest all the time. You’ve got to be cautious and don’t want to say the wrong thing.”

He’s also got a sense of humour, which is expressed most often in self-deprecation. At one point, he spoke about how his wife would “smack me on the side of the head” if he ever got cocky, and when asked to compare himself to Tiger, he pronounced it a “funny question.”

“I’m not going to remember the exact numbers,” he said. “But we’re playing at [Riviera] this year, and I hit my tee ball and this guy yells out, like, ‘Congrats on being No. 1 Scottie. Eleven more years to go.’”

As the journalists around him laughed, he gave a half-shrug at the self-evident truth of his own smallness in the face of those numbers. No need to explain the joke—just to punctuate by repeating the punchline.

“Eleven more years to go.”

Scottie Scheffler – David Cannon

So yes, there’s humanity there, and plenty of it. He’s admitted before that he’s quick to cry, and that he gets very nervous, and he said on Sunday that sheer, blinding, shout-out-loud excitement is part of his emotional register too, although by the time he finishes his post-victory obligations and finds a quiet place, the urge has often passed. Still, the unerring style of his game and his stolid appearance can’t help but attach an aura of inescapable dominance to the Scheffler experience. We’re in the thick of his personal dynasty at this precise moment, and though we know time will surely shuffle the deck and render him fallible, he is just now making us question the larger truth of impermanence in this sport.

Other fates might have come to pass. Xander Schauffele could have shot a 64 of his own. Clark’s putt could have fallen. Harman might have finished with four straight birdies. We know this to be true. And yet—yes—there it is again. The sense that nothing but the exact thing we saw could ever have happened; that the greatness we’re witnessing is both indifferent and inevitable. Welcome to the age of Scheffler.

Main Image: Jared C. Tilton