Legendary US Open story-makers. Golf Digest

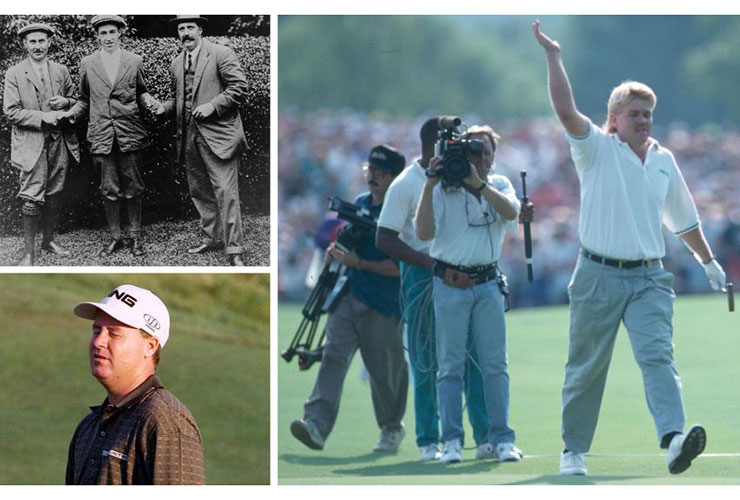

Francis Ouimet captured the 1913 US Open as a 20-year-old amateur, John Daly triumphed in the 1991 PGA Championship as an unknown rookie, and Bob May nearly downed Tiger Woods in his prime at the 2000 PGA.

In sport, heroism can be viewed through myriad prisms. It can be overcoming injury or illness. A true underdog coming to the fore over a single week. An aging athlete getting one more shot at glory or redemption. Or perhaps it’s the fusing of time and place and circumstance, when a competitor stirs spontaneous adoration from the cheering masses.

Golf offers more than its share when it comes to such circumstances. The combination of mental fortitude, emotional control and physical acumen is arguably unrivalled — mostly because success and failure rest in the mind and body of a single individual. And nowhere in the game is that more evident than in the four men’s major championships contested each year.

We got our latest taste of it only last month when California golf teaching pro Michael Block went into the PGA Championship week at Oak Hill as an unknown and emerged a bona-fide folk hero with his aw-shucks demeanour while contending into the weekend and making a final-round hole-in-one. It’s a story that resonated outside golf circles, and one that feels like it will be remembered for some time to come, even though Block finished just T-15.

That instant wave of devotion was sparked similarly for John Daly in the PGA Championship at Crooked Stick in 1991, though Long John triumphed and remained larger than life. Jason Gore became the Everyman hero in the 2005 US Open at Pinehurst, though he crashed and burned on the final day.

There are the enormous upsets. Jack Fleck over Ben Hogan, YE Yang outduelling Tiger Woods, and the ultimate shocker — young amateur Francis Ouimet winning a playoff over seasoned British pros Ted Ray and Harry Vardon in the 1913 US Open that put golf on the sporting map in America.

And if we really want heroic, consider life and death — as in Ken Venturi overcoming near-heat exhaustion to win the 1964 US Open and Hubert Green playing on amid a police escort because of death threats at Southern Hills in the 1977 US Open.

There are thrilling wins, dominating wins and historic wins, but not all of them are heroic, and some heroics don’t come with tangible victories. Instead, they inspire us in a way that makes them truly memorable, as is the case with the following 10 examples.

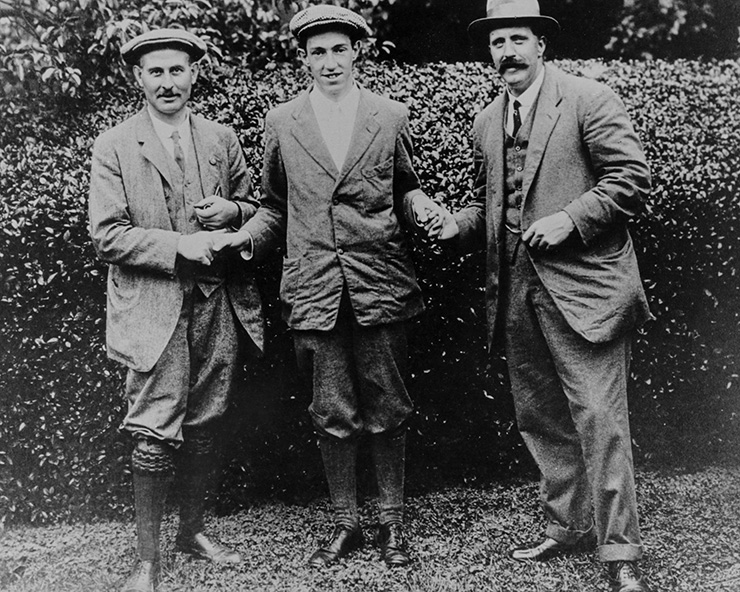

1913 US Open: Francis Ouimet

Francis Ouimet. PGA of America

No doubt there were some meaningful victories among the then-majors in the early part of the 20th century, especially considering the Open Championship in Britain had been contested since 1860. But, at least in the United States, none were more impactful than Ouimet’s story at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts. The details have been often told — Ouimet being raised in a poor family living across the street from The Country Club, and caddieing there was from the time he was 11 years old — but the incredible nature of the 20-year-old amateur’s victory never fades. Ouimet outduelled Vardon, already a five-time Open Championship winner by then, and Ray, who’d captured the Open Championship in 1912 and would win the US Open in 1914. With cherubic 10-year-old Eddie Lowery on his bag, Ouimet and the caddie became America’s first golf heroes, and it would remain that way for all of their lives.

2005 US Open: Jason Gore

Jason Gore walks off the 18th green after shooting 84 in the final round of the 2005 US Open. Streeter Lecka

Gore was on the verge of being labelled a journeyman when he arrived at Pinehurst that June. At 31, he’d won three times on what is now the developmental Korn Ferry Tour, but had played in just a single major to that point. Barrel-chested and jovial, Gore was an easy guy to root for, and that became apparent in the second round, when the Californian shot up the leaderboard at steamy Pinehurst with a 67 that tied him for the lead with Retief Goosen and Olin Brown. Goosen ended up taking a three-shot lead into Sunday, but the South African carried a flat personality, and it was Gore who easily became the gallery favourite. Alas, Gore and Goosen positively melted in the final round, shooting an astonishing 84 and 81, respectively, while New Zealand’s Michael Campbell secured his only major victory. Gore didn’t lose any confidence. He won three times that summer in the aftermath and earned a “battlefield” promotion to the PGA Tour, and he scored his only title in the big leagues later that September. And on that Sunday night in Pinehurst, when he might have been pouting in his room, Gore walked into a local sports bar alone, shared time with the locals and truly proved to be the all-time Everyman.

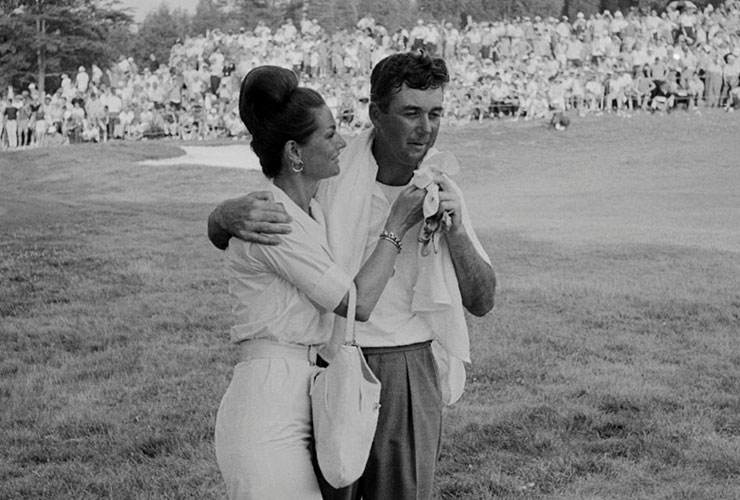

1964 US Open: Ken Venturi

An emotional Ken Venturi walks with his wife after he won the 1964 US Open. Wally McNamee

By the early 1960s, Venturi’s playing career was in a slide. His swing was affected by injuries suffered in a 1961 auto accident, and lean seasons followed. But in ’64, for reasons Venturi could never explain, he experienced a resurgence. And that led him to emerge from a US Open sectional qualifier to reach the national championship at Congressional Country Club. Washington DC was in the thralls of a brutal heat wave of 100-degree temperatures and high humidity — awful conditions for a field that had to play the final 36 holes on Saturday. Venturi shot 66 in the third round to trail Tommy Jacobs by two strokes. He’d began feeling ill on the 15th tee in the morning, and doctors were summoned to examine him. They surmised he could suffer heat stroke if he went back out for the second 18, but Venturi waved them off and wobbled down the final holes, shooting 70 to overtake Jacobs and earn what would be his only major title.

1991 PGA Championship: John Daly

The week’s eventual runner-up, Bruce Lietzke, considered athletic comparisons to what a long-bombing 25-year-old from Arkansas did to the field of veterans at Crooked Stick in Indiana, and the best thing he could come up with was Buster Douglas’ shocking defeat of Mike Tyson just over a year earlier. Truly, this was another long-shot knockout, with the country boy smashing his ball a country mile en route to a three-shot win as a rookie on the PGA Tour. The fans ate it up, and Daly, who got into the field as the ninth alternate, encouraged the connection by frequently waving his arms to the crowd. He only deepened the endearment when he went to an Indianapolis Colts preseason game on the night before the final round, seemingly without a care in the world. “I think everyone knows this is a Cinderella story for John Daly,” the champion said. “I feel so wonderful. … I think the fans won the tournament for me. They were super.”

1955 US Open: Jack Fleck

Jack Fleck (left) posted with Billy Casper (far right) and Webb Simpson after Simpson’s 2012 US Open victory at The Olympic Club. Stuart Franklin

Typewriters were already packed up. The script had its satisfying ending, or so everyone thought. When commentator Gene Sarazen signed off on the broadcast from San Francisco’s Olympic Club, Ben Hogan was declared the owner of a fifth US Open title. It was said he’d already donated his golf ball to the USGA. But late in the day, in an era when pairings weren’t arranged by leaderboard position, Iowa municipal-course pro Fleck rode a wave of back-nine birdies in shooting 67 to tie Hogan. Playing in front of a reported crowd of 10,000 on Sunday for an 18-hole playoff, most heartily rooting for the legend from Texas, Fleck shot 69 and won by three over Hogan, who announced his retirement right there in the aftermath. Fleck, then 32, had been heroic in another way, serving in the Second World War and being aboard a British ship off the coast of Normandy on D-Day. In golf, however, he’d never won any tournament of consequence. Years later, he was still entering tournaments, but disconsolate that he sometimes couldn’t break 80. As the US Open champion, Fleck was presented a cheque for $6,000 and quipped, “I think my wife will find some use for it.”

1995 Masters: Ben Crenshaw

Ben Crenshaw hugs his caddie Carl Jackson after winning the 1995 Masters. Jeff Haynes

There are victories that seem only attributable to fate, and that was the case for Crenshaw’s second win at Augusta National. Days before the ’95 Masters, Crenshaw’s lifetime mentor and coach, Harvey Penick, died. When Ben last saw Penick alive, the master gave Crenshaw advice on his putting grip and told him: “Just trust yourself.” When the news arrived that Penick had passed, Crenshaw and fellow Texan Tom Kite flew to Dallas for the funeral and returned late on Wednesday night before the Masters. They were emotionally spent and exhausted, and just making the weekend seemed like a chore. But Crenshaw would later say he felt unburdened. “There was this calmness about him all week that I have never seen before,” his wife Julie said. Using a set-up tip from his faithful Augusta caddie Carl Jackson, Crenshaw shot 14-under, beat Davis Love III by one shot and sobbed into Jackson’s chest after his final putt. “It was like I felt this hand on my shoulder, guiding me along,” Crenshaw said.

1977 US Open: Hubert Green

Hubert Green (in striped shirt) is escorted by police after anonymous death threat was called during Sunday play at Southern Hills in 1977. Heinz Kluetmeier

In the 122 editions of the US Open, there has never been anything like it. And hopefully there never will be again. At Southern Hills that June, Green was a pro who would eventually win 19 times on the PGA Tour but had never secured a major championship. He had admitted previously that his career would not be fully satisfying without one. And then, just as he was on his way to winning in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Green was informed on the 15th tee by local police that they’d received a call that there were a group of men on their way to the course who had threatened to shoot Green. The golfer did not cower, electing to play on with a phalanx of uniformed officers trailing him the rest of the way. Green declined to talk about the threat to reporters, but the USGA’s Sandy Tatum said: “It was one of the most remarkable exhibitions of grace under pressure that I’d ever seen.”

2000 PGA Championship: Bob May

Bob May and Tiger Woods hug after their dramatic playoff in the 2000 PGA. John Biever

Golf fans remember the playoff at Valhalla. They remember Tiger Woods dramatically following and pointing at his birdie putt on the first of three aggregate extra holes. They know that the triumph was Woods’ third in a major that season, and that eight months later, he’d complete the Tiger Slam in the 2001 Masters. But what is not committed to memory, and it should be, is how courageously May, an unheralded pro who had been a junior star years ahead of Woods in Southern California, battled the era’s greatest player to the very end. May shot 66 in each of the final three rounds and, playing in the final group with Woods on Sunday, matched Tiger’s 31 on the back nine. When Woods stuffed his approach shot close to the pin on the 72nd hole, May answered by draining a 15-footer for birdie. Beaten in the playoff, May was disappointed but hardly crushed. In 2014, he told the New York Post: “The only thing that would have changed was the financial aspect. Other than that, I think I got as much recognition for finishing second the way it happened than if I would have won it.”

2009 PGA Championship: YE Yang

YE Yang celebrates making a birdie putt on the 72nd hole in his victory over Tiger Woods in the 2009 PGA. David Cannon

There would be a second Bob May-type character Woods would face in his major career, and this time it was the superstar who faltered — badly — shooting 75 in the final round at Hazeltine National in losing to the 110th-ranked player in the world, South Korea’s Young-eun “YE” Yang. Given the circumstances — trying to become the first player in Woods’ majors career to chase him down when he held a 54-hole lead — Yang was remarkably composed … until making birdie on the 72nd hole for a closing 70 and fist-pumping like crazy in front of Woods. Yang’s victory was celebrated in faraway cities, with him being the first Asian to win a men’s major. “I’ve sort of visualized this quite a few times,” said Yang, who was 31 at the time. “Playing against the best player in the history of golf, playing with him in the final round of a major, I have always dreamed about this.”

2009 Open Championship: Tom Watson

Tom Watson was a par at 18 from winning the 138th Open Championship, but ended up losing in a playoff to fellow American Stewart Cink. David Cannon

There were deserved accolades when Phil Mickelson, at 50, became the oldest major championship winner in the 2021 PGA at Kiawah. Now consider: Watson was 59, and 11 years removed from his last regular-tour victory, when he needed but a par on the 72nd hole at Turnberry to score one of the most remarkable victories of all-time. Beloved in Britain as much as any American for his five Open wins, Watson’s name seemed destined for the Claret Jug again when he birdied the 17th. But he overshot the green at 18 and bogeyed to fall into a tie with Stewart Cink. Through no fault of his own, Cink made grown-ups cry in living rooms around the world when he went on to shoot two-under to Watson’s four-over in the four-hole playoff. “In my profession when you have a chance to win the World Open, as I call it, and you give it away as I did, it is a big disappointment,” Watson said. Nevertheless, his show of grit remains the greatest of any “senior” in a major.