By Shane Ryan

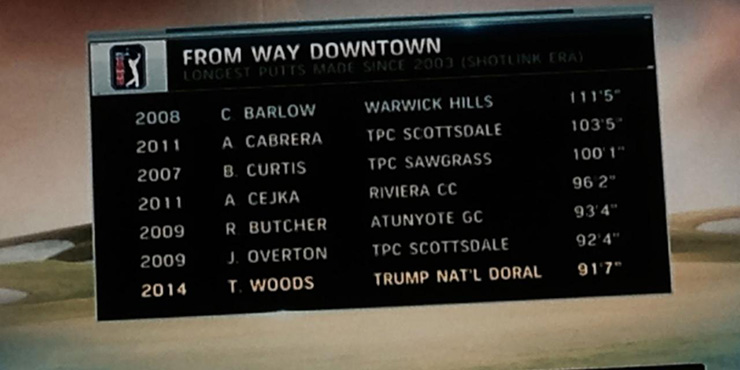

In 2014, on Friday at the WGC-Cadillac Championship in Doral, Tiger Woods buried a 91-foot, 8-inch putt on the fourth hole. Twenty-five hundred miles away in Las Vegas, Craig Barlow happened to be watching the Golf Channel when they put up a graphic comparing Tiger’s bomb to the longest putts ever made on the PGA Tour. It didn’t surprise him when he saw his own name at the top of that list—he’d seen it in this context before—but this time, he managed to snap a picture with his phone before it disappeared:

There it was: 2008, C Barlow, Warwick Hills, 111’ 5”. A putt so long that it would be a mathematical impossibility on most greens. You might expect that seeing his name on TV would give Barlow a jolt of pride, and it did—the recognition was nice, and that particular Buick Open was important to him for reasons that went beyond the putt.

But he also laughed. And he laughed again when we spoke on the phone from his home in Nevada earlier this month.

“If people only knew,” he said.

Knew what?

“The longest putt ever made on tour wasn’t actually a putt.”

• • •

There has been something a little mysterious to me about Barlow’s putt since I first saw the number earlier this year on the PGA Tour statistics page. The strangeness mostly stems from the fact that no video footage exists of it. The year 2008 is not exactly the technological dark ages, yet search as you will, you won’t find a video clip. Imagine if we couldn’t see the longest NFL touchdown run in the last 20 years, or Major League Baseball’s longest home run.

That’s not to say it’s a secret—you can find reference to Barlow’s feat all over the Internet. Some outlets correctly include the caveat that it’s the longest putt we know about, since the down-to-the-inch Shotlink data only goes back to 2003. The frankly absurd length of the bomb makes it somewhat likely that it is, in fact, the longest putt ever made on tour, but we don’t know for sure and we never will.

Primed for an odd story, then, it didn’t surprise me when Barlow said at the start of our call that the “coolest part” about the putt would either add spice to the story or ruin it completely.

Because—again—it wasn’t a putt.

By Sunday morning at the 2008 Buick Open in Warwick Hills, Barlow, 35 at the time, had already completed the hard part of his week. He’s what you’d call a journeyman in professional golf, a former full-time tour member who made a lot money since his rookie season in 1998—including more than a $1 million in 2006 after consecutive top 10s at Pebble Beach and Riviera. But Barlow never won an event and wouldn’t be considered a household name among casual sports fans. About six weeks before the Buick Open, he’d lost his exempt status for the first time in a decade, and at that point his career ambitions were aimed at a specific goal: 150 made cuts.

It was more than just an arbitrary number; reaching 150 made cuts makes you a “veteran member,” which confers perks like TPC privileges for life, health insurance and an exemption category that can earn you entry into other tournaments. Barlow had watched veteran members like Willie Wood, Mike Stanley and Mike Springer play as many as 15 tournaments a year purely on the strength of that status. As fate would have it, veteran-member status would soon diminish in importance with changes on tour, but that was the goal he was chasing, and in the summer of 2008 he was stuck at 148.

The year had been a grind. Since losing his status, he’d missed a handful of cuts and was forced to play the Monday qualifier at Warwick Hills in late June, just outside Flint, Mich., for a chance to make the Buick Open field. He survived that day, and then made the tournament cut by three strokes, which gave him 149 for his career—one off from the magic mark.

RELATED: 10 remarkable season-ending stats from the 2019-’20 PGA Tour season

Come Sunday, he was in a relatively casual state of mind on the first hole, a par-5 dogleg right heading away from the clubhouse. He’d already made the cut, but wasn’t especially close to the leaders. It would take all of his length to reach in two, but with little to lose, he gave it a crack with driver and 3-wood. When he approached the green, he saw that his ball had crawled its way onto the front right of the putting surface by no more than an inch or two.

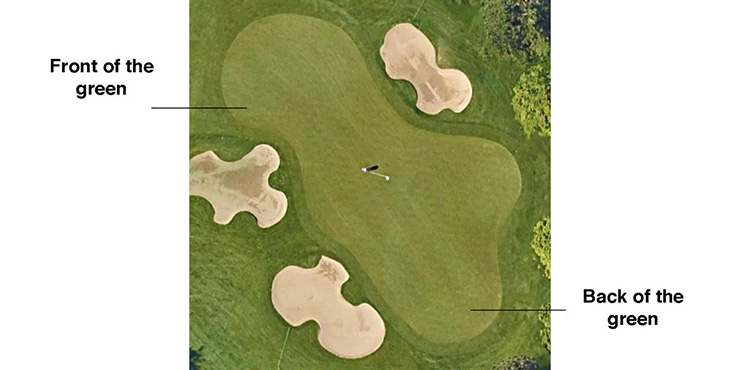

The problem? The hole was back right, and the green was a three-tiered sprawling leviathan. The 111-foot distance was daunting enough, but it was the bunker directly in his path that presented the biggest complication. In this screenshot of a satellite image, from Google Maps, you can see where Barlow’s ball would have been, in the top left, tucked behind the bunker, miles from the pin, which was placed that Sunday in the lower right:

Instead, he took out his lob wedge. Just as he was about to hit the ball, he remembered something—his caddie, Don Thom, wasn’t tending the pin. Even though he wasn’t technically putting, his ball was on the green, and in 2008 you couldn’t leave the flagstick in. The thought came to him just in time, and Thom raced to the flag.

Barlow isn’t afraid to call the shot that followed “amazing.” He landed his pitch softly on the upper tier, where it bounced once or twice, checked and trickled toward Thom, who pulled the pin. Barlow couldn’t even see the hole from where he was standing, but he saw the ball disappear, and he heard the roar of the 50 or so people standing around the green. He recalls the scene vividly, because even at the time it seemed to play out for him in slow motion. And he remembers he and Thom reacting the same way he’d react years later when he saw the moment resurrected on TV as a “putt.”

By laughing.

• • •

Of course, he had no idea that he’d accomplished something historic, if arcane. His chief concern was reaching 150 cuts, and now he was one away. Even today, his instinct is to downplay the significance of the pseudo-putt.

“I don’t want to diminish it by saying it didn’t matter, because of course any time you make an amazing shot it matters,” he said, “but I’d rather have the record of the lowest score ever at a tournament, or the biggest winning margin.”

Craig Barlow putting at a British Open qualifier the Monday after his historic ‘putt’. (Domenic Centofanti/Getty Images)

The historic aftermath of that eagle was as strange as the circumstance itself. First, any shot from the green is technically classified as a “putt” even if the putter itself isn’t used. (Conversely, a ball that is putted from off the green doesn’t count as a putt, to Sangmoon Bae’s regret.) Second, as the references to Barlow on the Internet make clear, very few people seem to understand that he used a lob wedge in the first place. Some sources even include descriptions of him putting the ball, which is particularly funny considering what really happened.

As for Barlow, he was cursed in the short term to exist in a mental state that did him no psychological favours: thinking about the cut. But he took his chances where he could, and a year later, at the same course, he came into his last hole on Friday needing a par to reach his private milestone. He opted for 3-iron off the ninth tee—“I was sick of hitting into the trees my whole career,” he joked—reached the green safely, lagged and tapped in for his 150th made cut. That final putt was mere inches, but it was more meaningful to him by far than the record-breaker from a year before.

Even with the weakened status of the veteran member, Barlow’s successful quest for 150 allowed him to play in dozens of tournaments in the subsequent years, and earn hundreds of thousands of dollars. He played his last tournament in 2018, and today, at 48, he’s the director of instruction at Lake Las Vegas and the High Performance Golf Institute. He’s thinking of taking a crack at the PGA Tour Champions when the time comes, but has plenty of family concerns to think about before he makes the leap.

In the meantime, he only thinks about his record-breaking putt when he’s asked by a journalist, or when a junior he’s coaching wants to know about his tour days. When that happens, he’ll pull out his phone and show them the Golf Channel screenshot, with his name six spots above the great Tiger Woods.

“They’ve all gotten to see that,” he said. “But I’ll be honest. … I haven’t really told them all it was a chip.”