By Bill Fields

Well before the teenager tacked one golf legend’s achievements on his bedroom wall for inspiration—a newspaper-clipping timeline of Jack Nicklaus’ milestones—the child took a 75-mile trip from his home in Cypress, Calif., and teed it up with another icon.

It was 1982. Tiger Woods, only 6 years old, got in a car with his cut-down clubs; his father, Earl; and his then-golf instructor, Rudy Duran, for the ride east to San Jacinto, where

was waiting to conduct an exhibition at the Soboba Springs course.

“I think I asked Tiger if he knew who Sam Snead was, and he didn’t know,” Duran recalls. “He really didn’t care. He was 6. It was a fundraiser where Snead played two holes with a bunch of donors. Tiger and I did a little exhibition before Sam’s clinic, then Snead played the 18 holes.”

A couple of those holes were with Tiger, who already was showing an unusual affinity and aptitude for golf. His drives couldn’t yet travel the length of a football field, but the other ingredients were all there.

“Tiger was a shrunken touring pro at 5 or 6,” Duran says. “He was shooting eight under his ‘personal par,’ playing the ball as it lies, picking his own strategies, holing every putt, playing by the rules. He was effectively playing like a touring pro.”

Sam and Tiger traded autographs that day. Soon, they likely will be trading places.

• • •

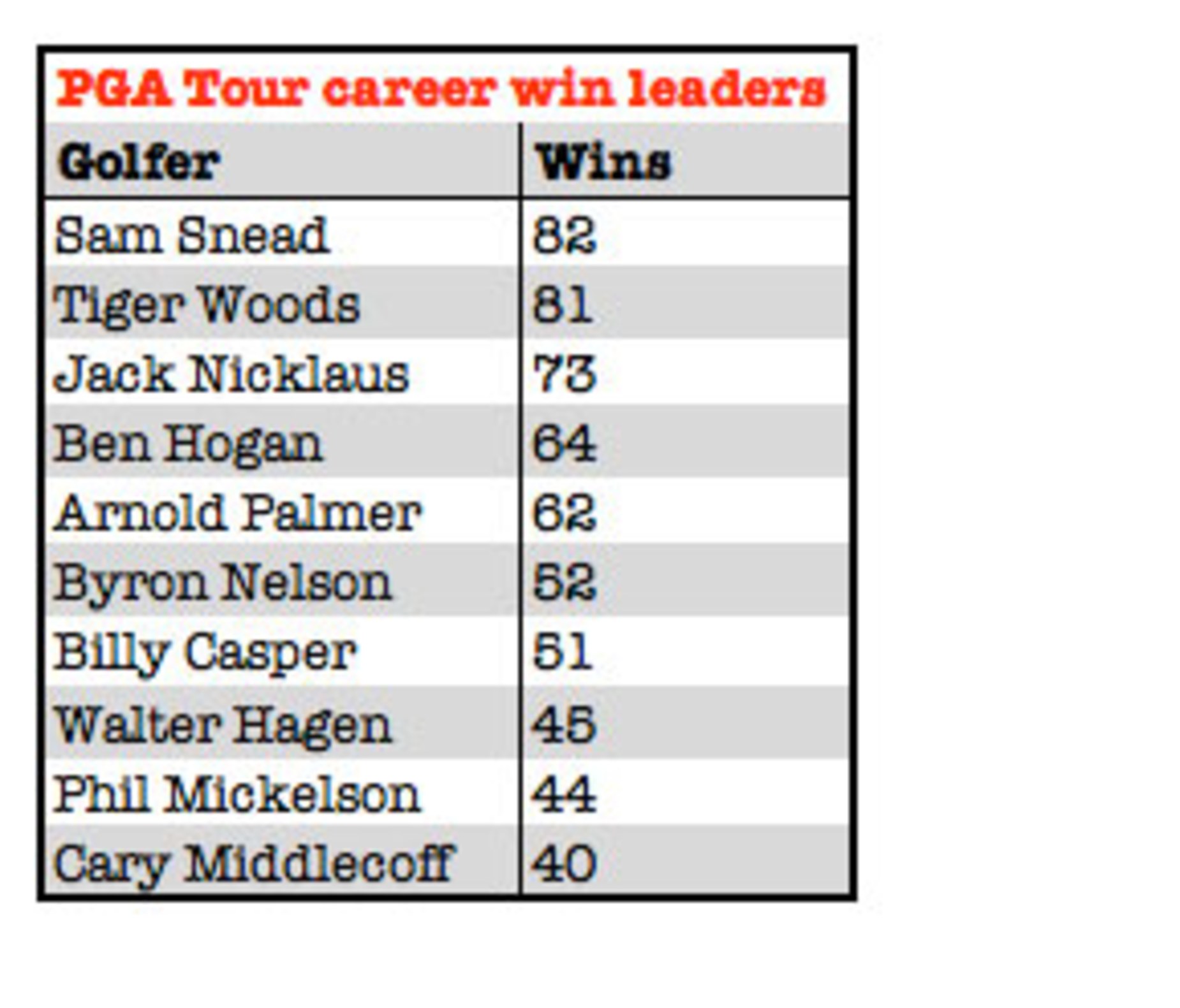

Woods, with 81 career PGA Tour victories following his win at the Masters last month, is closing in on Snead’s all-time tour record of 82. It is a benchmark that some consider too low (because Snead had some victories removed that should count) and others think Woods already has surpassed (because Snead gets credit for wins that wouldn’t be official under current PGA Tour parameters).

“Tiger’s record is clearer, cleaner,” says Al Barkow, a golf historian and Snead biographer. “In Sam’s day, things were pretty loose. Records were kept on envelopes. Winning is winning, but it’s very hard to compare eras. Course conditions and equipment are so different. Sam played a lot of tournaments when even the pros had a hard time getting golf balls. He told me once, if you got a good ball during the war years, you’d play it until you could pinch it soft in your hands.”

There is nothing soft about the competitive core of Snead nor Woods, which goes a long way to explain why they’re at the summit of the PGA Tour victory category, only Nicklaus (73) within 15 wins. When Byron Nelson told Barkow in Gettin’ to the Dance Floor that “winners are a different breed of cat,” he could have been speaking about Snead, Woods or Kathy Whitworth, whose 88 victories are the most in LPGA history.

“The whole thing about playing was to win,” Whitworth says. “My attitude is, be the best at what you do, whatever that is. Jack, Sam, Ben [Hogan], Tiger, me—the whole purpose, the fun, was to try to win. We didn’t always, but it was in the trying.”

Slammin’ Sam saw the effort Tiger put into his game when they met in ’82, as the child insisted on playing a partially submerged ball out of a water hazard on his first hole with the legend, a par 3. (When Woods has recalled his boyhood encounter with Snead, he has placed it as happening at Calabasas Country Club, but Duran and photographs of the day put it at Soboba Springs; the year before, a “Today” Show feature on the prodigy was filmed at Calabasas.)

“I got in there to play it and the ball was sitting up, but from behind me Sam yells, ‘What are you doing?’ ” Woods said in 2000. “I look around, look dumbfounded. I’m going to hit the shot. He says, ‘Just pick it up and drop it. Let’s go on.’ I didn’t like that very much.”

Duran and Earl Woods watched to see what Tiger would do, knowing the recovery shot would make him a wet, muddy mess. “Tiger kind of looked at Snead kind of funny and got his iron out and hit it on the green,” Duran says. “Sam shook his head like, ‘That’s pretty good.’ Tiger two-putted for what I would have called a Tiger par, because he was only hitting it about 90 yards if he killed it off the tee.”

• • •

Seven years before, in his early 60s and still contending for titles on the PGA Tour—a decade after his final win, at the Greater Greensboro Open in 1965—Snead summed up his driven mindset. “Quit competing,” he told Sports Illustrated, “and you dry up like a peach seed.”

When Woods turned pro in 1996 after winning the U.S. Amateur an unprecedented three consecutive times, the spark he displayed against Snead was a roaring flame as he made his debut in the Greater Milwaukee Open. In a sit-down following the first round with two-time U.S. Open champion and 17-time PGA Tour winner Curtis Strange, then doing television for ABC, Woods explained his thirst for winning in blunt terms that took his interviewer, a fierce competitor himself, aback.

“I’ve always figured why go to a tournament if you’re not going there to try and win,” Woods said. “There’s really no point in even going. That’s the attitude I’ve always had my entire life, and that’s the attitude I’ll always have. I always explained to my Dad, ‘Second sucks and third’s even worse.’ ”

Slightly less than four years later, in the 2000 Bell Canadian Open at Glen Abbey outside Toronto, Woods wrapped up his ninth win of the year with a mind-blowing 6-iron from a fairway bunker over a lake on the 72nd hole. The victory came on the heels of three consecutive major titles that summer and gave him more wins in a season than anyone since Snead won 11 titles in 1950.

From his Virginia home that afternoon, Snead acknowledged the differences between his tour days and Tiger’s, but gave him his due. “Nope,” Snead said, “I didn’t think anybody that good would come along, but he has.”

The 2000 Canadian Open was Woods’ 24th tour victory, allowing him to get to that number a year earlier in his career than Snead when he captured that tournament for win No. 24 (as denoted in the 2019 accounting of Snead’s victories) in 1941, his fifth full year on the circuit.

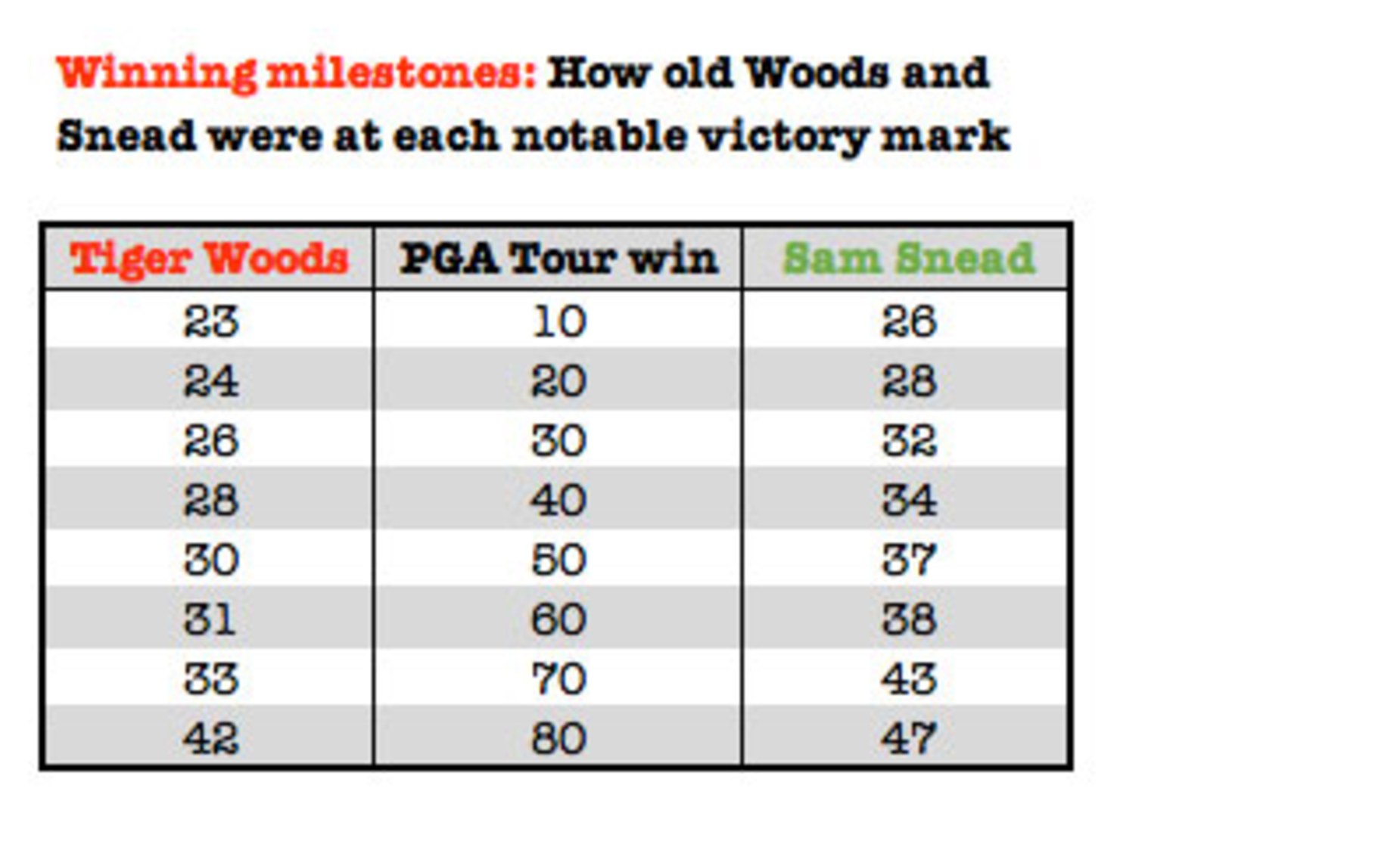

Woods would continue to reach milestones a bit sooner than Snead, using each golfer’s current tour-acknowledged victories. For their 40th wins, Woods was 28, Snead 34. Tiger won No. 50 in 2006 at age 30, seven years younger than Snead at the same total. Woods’ 60th came when he was 31, 70th at 33 and 80th last fall, at the Tour Championship, when he was 42. Snead reached 60 wins at 38, 70 at 43 and 80 when he was 47.

“Ever since Tiger hit 70 wins and they started to talk about Sam’s 82, the best thing for me is that Sam is getting the attention he’s much deserved over the years,” Strange says. “It has helped make Sam relevant in today’s time and been a great reminder of how great Sam was.”

Strange was the age Tiger was in 1982 when he met Snead in 1960, after Strange’s father, Tom, got a job working for Snead at The Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, W.Va. Tom Strange spent two years there, soaking up the smooth goodness of Sam’s swing and passing along the ideal to his golf-loving twin boys, Curtis and Allan, each of whom as teenagers tried to mimic the Snead action. As the late tour pro John Schlee observed, “watching Sam Snead practice hitting golf balls is like watching a fish practice swimming.”

When Curtis got on tour in 1977, he eagerly enjoyed practice rounds with Snead when he ventured out to his old stomping grounds when most of his contemporaries had their feet up. Snead was still sharp, still hungry.

“Getting ready for a practice round at the Disney team event one year with Phil Hancock, Keith Fergus and me, Sam got on the first tee and said, ‘Boys, what are we going to play for?’ ” Strange says. “Keith said, ‘Mr. Snead, we just want to practice today—we don’t want to play for anything.’ Sam put his driver back in the bag and left the tee. We didn’t see him until the next day. My goodness, he was competitive, just like Tiger. Those people don’t show up on the corner every day.”

• • •

Just how formidable is it to get to 80-plus PGA Tour victories? Woods, Phil Mickelson (44 wins), Tom Watson (39) and Vijay Singh (34) are the only golfers born after World War II with more than 30. When Dustin Johnson won the WGC-Mexico Championship earlier this season, he became the first golfer born after 1980 to reach 20 PGA Tour victories.

When Snead won the individual portion of the 1961 Canada Cup—later called the World Cup—Sports Illustrated wrote that it was his 110th tournament victory. The Associated Press noted Snead was the winner of more than 100 events after his 1965 Greensboro triumph. No doubt those tallies included Snead’s 17 West Virginia Open victories. Those were discounted years ago by the PGA Tour, which for decades put Snead’s total at 84.

That was the number Whitworth eclipsed on July 22, 1984, at the Rochester International, with her 85th career LPGA victory, an occasion that drew a lot of attention—a woman breaking a record long held by a famous male athlete.

“I was relieved,” Whitworth says. “I hadn’t won in over a year and the press was just constant in talking about the possibility. Sam was real sweet. They had him on the phone in the press room that evening. He congratulated me. We were friends, and I had gotten to play with Sam several times.”

Bettmann

On the LPGA Tour, Whitworth holds the all-time victory mark with 88.

Snead was 72 when Whitworth bettered his mark, still shooting his age and still extremely proud, as the conversation, reported by the Democrat and Chronicle newspaper, made clear. “You’re a great player,” Snead told Whitworth, “and you know who’s the greatest.”

“You, Sam,” Whitworth said.

“Right. You know that,” said Snead, who later on the call noted, “The only thing that makes me so damn mad is that they won’t give me credit for the ones I won.”

In 1986, the PGA Tour began a statistical analysis of events played between 1934 and 1979—when record-keeping was sometimes incomplete or wrong—to facilitate a ranking of players in different eras. The following year, Snead’s victory total was reduced from 84 to 81, a decision made by a panel convened by then-PGA Tour commissioner Deane Beman to further sort out official versus unofficial wins over the long arc of the American professional circuit. The group—Barkow and fellow writer Herbert Warren Wind; former golf administrators Joe Dey, Jack Tuthill and Joe Black; former tour player Jay Hebert; tour employees Gary Becka, Cliff Holtzclaw and Steve Rankin—considered purse size, field strength and historic significance in an afternoon meeting at the 1987 Masters.

“As a group, we were far too casual in our task …” Barkow wrote two decades later in Golf World, of a process that resulted in adjustments to the win counts of Snead and other players of the mid-20th century.

As Laury Livsey reported in a detailed article on PGATour.com earlier this year, the panel removed nine wins and added six—including four “Crosbys”—to Snead’s official tally, resulting in a net loss of three victories. (Snead’s total was boosted to 82 when the tour decided in 2002 to count Open Championship wins as official victories for those who triumphed before 1995, the year they started to be included in PGA Tour tallies; Snead won the 1946 Open at St. Andrews in his only appearance in golf’s oldest major.)

Snead’s revised total was hurt most by the elimination of five titles from 1952 to 1961 in the Greenbrier Invitational/Sam Snead Festival, which attracted a good field but sometimes was held the same week as another invitational event. A remaining quirk in the record Woods is on the verge of tying is that Snead still gets credit for the 1936 West Virginia Closed Pro—his first credited win, when he shot 70-61 and won by 16 strokes over a field of area pros—but not for his 1949 North and South title earned at Pinehurst No. 2 over a deeper roster of tour regulars in an event considered throughout its history as one of the most important on the circuit. Oddly, Snead gets official credit for his two other North and South victories.

“It’s easy to say for Tiger what was official,” Snead friend and attorney Jack Vardaman, who has passionately argued that Snead’s total be restored, told Livsey. “It’s much, much harder to say that for Sam’s career.”

Bettmann

While acknowledging the difficulty of comparing eras, current PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan is sticking by decisions made by the 1987 panel members. “I am confident they made the best possible decisions based on available information,” Monahan said on the tour’s website, “and I trust their judgment.”

Snead died on May 23, 2002, at 89, when Woods was more than 50 victories from catching him but already had displayed a repertoire of skills that all the greats, including Sam, acknowledged. Not long before he died, though, Snead made it clear he would have loved the challenge of squaring off again with the prodigy who had him shaking his head way back in 1982.

“Could I have whipped Tiger Woods? Hell, yes,” Snead wrote in Golf Digest. “In my prime I could do anything with a golf ball I wanted. No man scared me on the golf course.”

The day before Snead passed away, Woods was giving a news conference at the Memorial, talking about what motivated him. “The most joy I get is going out there and winning championships and beating everybody in the field,” Tiger said. “That, to me, is fun. It’s knowing the fact that when I go home on a Sunday night that no one else beat me.”

Soon, Woods might be going home on a Sunday night having beaten one of the greats.

“Sam would tear it up if he were playing today,” says Barkow, who saw Snead play for the first time in the 1940s. “But Tiger’s a great player, no question about it. Some of the things he has done, the kinds of shots he has hit under pressure, they were phenomenal. If he gets to 83 or 84 wins or whatever it is, I don’t think anybody ever breaks it.”