Raise a glass to the legendary writer, whose voice and laughs will live forever

By Tom Callahan

Dan Jenkins, the Hall of Fame golf writer and Golf Digest Writer-at-Large, died Thursday night, March 7, at 90. His longtime colleague, Golf Digest Contributing Editor Tom Callahan, writes this tribute.

When his grandmother found an old typewriter in the attic, only child Dan Jenkins of Texas became a writer.

Word for word, he typed the war dispatches and sports columns from the Fort Worth papers, pretending to be a newspaperman. But, eventually, he changed the words, giving them an edge, his own edge.

An aunt named Inez owned a drugstore, a repository of dreams. Luxuriating in the store’s delicious aromas, Dan set up camp at the out-of-town newspapers stack. For a while, his favourite lead was by Damon Runyon from an account of Chicago mobster Al Capone’s tax-evasion trial: “Al Capone was quietly dressed when he arrived at the courthouse this morning except for a hat of pearly white, emblematic, no doubt, of purity.”

Jenkins also admired James Thurber’s take on one of Ohio State’s athletic stars, Chic Harley: “If you never saw Harley run with a football, words cannot describe. It wasn’t like [Red] Grange or [Tom] Harmon or anybody else. It was kind of a cross between music and cannon fire, and it brought your heart up under your ears.”

But in time Jenkins switched his allegiance to this opener from John Lardner: “Stanley Ketchel [the middleweight boxing champion] was 24 years old when he was fatally shot in the back by the common-law husband of the lady who was cooking his breakfast.”

“That, in a sentence,” Dan always said, “is the great American novel.” And it had to be “lady.”

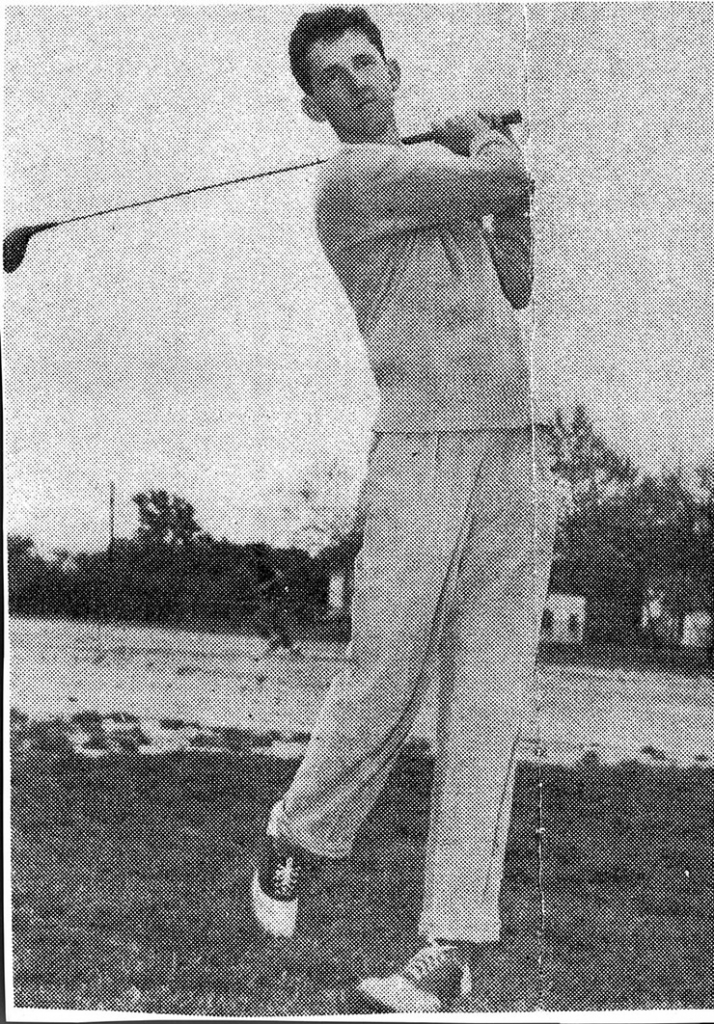

Jenkins was a solid player in his own right.

His father was a scratch golfer, but it was Aunt Inez who presented Jenkins his original set of clubs, ladies’ clubs: 2-, 5-, 7- and 9-irons, a spoon (3-wood) and a putter. At age 12, he reached the first of 232 major championships, the 1941 U.S. Open at Colonial Country Club. It was magical. Dan had never beheld bentgrass greens before. They looked like Ireland (or at least what he thought Ireland should look like). His home course, nine-hole Katy Lake, didn’t even have sand greens. They were made of dark-brown cottonseed hulls, oiled down or they’d blow away, requiring raking before putting.

There’s a black-and-white photograph from a practice round at the ’41 Open. It features Byron Nelson, Gene Sarazen, Tommy Armour and defending champion Lawson Little (once “the best amateur golfer who wasn’t Bobby Jones”) walking a fairway in the foreground. In the background, wearing a striped polo shirt and white duck trousers with a ticket lashed to his belt, Boy Jenkins is trailing them. (This is the only documented proof that he was ever actually on the golf course during a major, where he would spend most of his time raconteuring on the verandas and out-writing everybody in the press rooms.)

A mischievous caption, ballooning from Sarazen’s lips, says, “If that little kid behind us grows up to be a golf writer, this game is in big trouble.”

• • •

For the Paschal (High) Pantherette, he wrote a parody of the local sportswriters. Someone sent it to Blackie Sherrod, the nut-brown, task-mastering, Cherokee-blooded sports editor of the Fort Worth Press, who would paint the battlefield at Little Bighorn in red splashes of horrible realism but with the Goodyear blimp floating overhead. Blackie hired Jenkins while he was still in high school and sent him on to Texas Christian University (to letter in golf) with a byline.

Blackie’s Boys—all of whom became eminences—included Gary Cartwright, Jerre R. Todd and Bud Shrake, who like Dan was destined for Sports Illustrated, best-seller lists and screenwriting credits. Bud and Dan joined in occasional collaborations and were inseparable friends.

Sherrod pointed his young staff to the files of stylish writers, such as Red Smith, and once again Jenkins broke in as an imitator. Henry McLemore, covering the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, wrote, “It is now Thursday. The Olympic marathon was run on Tuesday, and I am still waiting for the Americans to finish.” So Dan kicked off a high school football story this way: “It is now Monday. Birdville played Handley on Friday night, and I’m still waiting for Bubba Dean Stanley to complete a pass.”

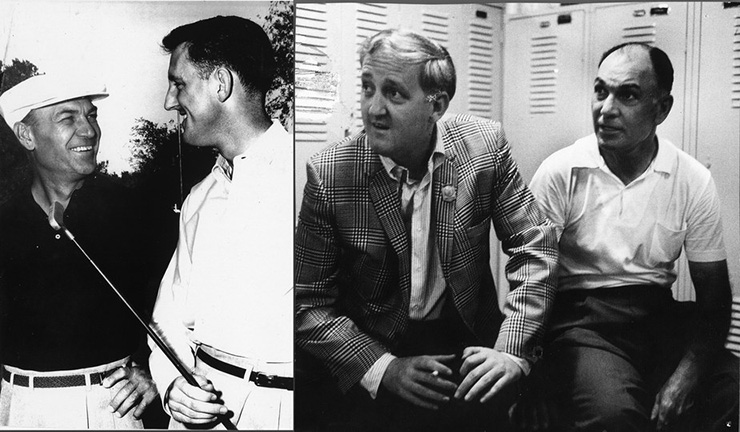

Jenkins admiration for Hogan started when he first covered the local golfer for the Fort Worth newspaper and lasted a lifetime.

But pretty soon, just like before, he found his own words, his own voice. It was a blend of prairie-twang and ranch-hand nasalness softened by and cultivated with a surprising lilt of sophistication. He was willing to be funny, but only if it was true.

“Missouri’s Dan Devine looked like a man who just learned that his disease was incurable. He was leaning against a table in the silent gloom of his locker room, a towel around his neck, a paper cup of water in his hand, whip-dog tired, and his large brown eyes fixed vacantly on a lot of things that could have happened.”

Sherrod called Jenkins “a news dog” and “the most effortless writer I’ve ever known. The most confident, too. Most writers, they’re insecure to the point of hiding under the bed. Dan always had the attitude of a competent athlete—and he was a good athlete. Golf. Basketball. Pool. I think he could’ve roped buffaloes. Nothing in the world spooked Dan except snakes. Just a picture of a reptile would crater him. We spent a lot of time rolling snake photos into his typewriter. He’d come sailing in, smoking his 19th cigarette of the morning and drinking his 12th Coke. When he rolled his typewriter carriage, out would jump this hideous rattler. And Dan would beat and thresh and fall down in wastebaskets. Then he’d sigh and sit down and, once he quit trembling, write you the best 800 newspaper words you ever read.

“If every college football team had a linebacker like Dick Butkus, all fullbacks would soon be three feet tall and sing soprano.”

Dan’s inaugural and eternal hero (along with Texas footballers Doak Walker and Bobby Layne) was Ben Hogan, his local assignment on the golf beat. They played some 40 rounds together, often just the two of them. “I’d be watching him practice,” Jenkins said, “and he’d say, ‘Let’s go.’

“In 1956, Ben called me up and said, ‘I want you in a foursome for an exhibition at Colonial benefiting the Olympic Games.’ I said, ‘OK, I guess, but there must be somebody better than me.’ ‘No, I want you,’ he said. I worked half a day at the paper, came out, didn’t even have a golf shirt, wore a dress shirt, rolled up the sleeves, changed my shoes, didn’t hit a practice ball, got to the first tee, and 5,000 people were waiting. Now, what do you do? Somehow I got off a decent drive into the fairway, and proceeded to top a 3-wood 50 yards—it was a par 5—then topped another 3-wood, then topped a 5-iron. All I wanted to do was dig a hole and bury myself in the ground forever. As I was walking to the next shot, still 100 yards from the green, Hogan came up beside me and said, ‘You could probably swing faster if you tried hard enough.’ I slowed it down, got calm, and shot 76. He shot his usual 67. That’s the Hogan I knew.”

Ben gave him other tips, some of them incomprehensible, like “always over-club downwind.” Famously, Hogan was said to harbour a “secret,” but Jenkins reckoned the real secret was just practice. Dan was an uncommonly fine putter, and Hogan volunteered to tutor him for six months in the rest of the shots if he wanted to take a crack at the U.S. Amateur. When Jenkins told Ben he was already doing what he always wanted to do, Hogan didn’t really understand. But the gruff nod of trust he tossed Dan that day never left Dan’s heart.

So when a slightly younger writer and friend would say, “Yeah, that Hogan must have been awfully good; some weeks he beat both Jay Hebert and Lionel Hebert,” Dan would just smile tolerantly, secure in his conviction that he knew more than anybody else about golf.

Dan never threw over Hogan, but he moved over to Arnold Palmer with ease, cued by gentleman Marine Jay Hebert (pronounced A-Bear), whom Dan asked one morning, “What are on the list of qualities helping Ken Venturi become the next great golfer?”

Hebert answered, “Venturi’s not the next great golfer. Arnold Palmer is.”

Arnold Palmer? Dan thought. The guy who can’t keep his shirttail in? The guy who thinks he can drive a ball through a tree trunk? “Why him?”

“Because he’s longer than most of us,” Hebert said, “and he makes six birdies a round. He also makes six bogeys, but one of these days he’s going to eliminate the bogeys.”

“He did,” Jenkins said, “and the sports world became a more exciting place.”

Along with his loud, lovable friend, Bob Drum of the Pittsburgh Press—right to Palmer’s face between the third and fourth rounds of the 1960 Open—Jenkins belittled anyone’s chances of coming from seven strokes and 14 players behind. But when Palmer drove the par-4 first green at Cherry Hills and went out in 30, here came Drum and Jenkins on the dead run to the 10th tee. Relieving Jenkins of a Coca-Cola and a pack of Winstons, Arnie said, “Fancy meeting you guys here.”

Jenkins could say things pretty quickly, too, if he wanted. (“I don’t suppose anybody’s ever enjoyed being who they are more than Arnold enjoyed being Arnold Palmer.”) But Dan caught Palmer best at the close of his exquisitely titled book, The Dogged Victims of Inexorable Fate when he wrote: “This is true, I think. He is the most immeasurable of all golf champions. But this is not entirely because of all that he has won, or because of that mysterious fury with which he has managed to rally himself. It is partly because of the nobility he has brought to losing. And more than anything, it is true because of the pure, unmixed joy he has brought to trying. He has been, after all, the doggedest victim of us all.”

• • •

Like every Texan, Dan loved college football as well, though his first novel, 1972 wildfire Semi-Tough, was set in the National Football League. (“I always knew,” Jenkins said, “that someday I was going to write a book called Semi-Tough.”) Dandy Don Meredith, the ex-Cowboy quarterback who made a foil of Howard Cosell on “Monday Night Football,” appeared to have memorized every passage, sprinkling Billy Clyde Puckett references throughout his conversation (confusing Cosell).

“What I love about Jenkins,” Meredith said, “is he takes himself funny but the games serious.”

Jenkins held the classified combination to all the sainted college coaches, like Darrell Royal of the University of Texas and Paul (Bear) Bryant of Alabama, mainly because Dan was preternaturally resistant to soft soap and had a nose that twitched automatically at any odour of the bull. “You see that helmet over there?” Bryant told him in the Bear’s office at Tuscaloosa. “That’s Lee Roy Jordan’s helmet. He was the greatest hitter I ever had. You look at that helmet real close, you’ll see on there the colour of every team we played. A little orange for Tennessee, a little maroon for Mississippi State …”

“C’mon, Bear,” Dan interrupted, “who’s the artist who painted it? I know you all wash the helmets after every game.”

“Goddammit,” Bryant exclaimed, “it works on recruits!”

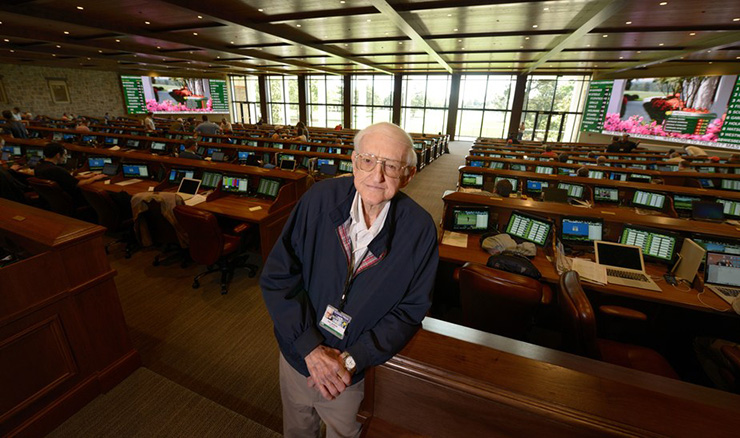

Dan Jenkins inside the new press centre at the Masters during the final round of the 2017 tournament in Augusta, Ga. (Dom Furore)

Texas Christian head coach Gary Patterson said, “Dan can be my biggest critic, but that’s all right because he loves TCU. There might be somebody out there who knows a lot of football, but I don’t think there’s anybody out there who knows as much about the history, not only of TCU but of all college football, as what Dan Jenkins does.” After the Horned Frogs won the 2011 Rose Bowl to complete a perfect season, Dan was shocked to receive a championship ring engraved Jenkins. The press box at TCU’s Amon G. Carter stadium also bears his name.

Old Baltimore Colts special teamer Alex Hawkins, known as Captain Who? (“Gentlemen, this is Captain Unitas, Captain Marchetti and … ”) had mounted on his living-room wall framed photographs of Johnny Unitas, Gino Marchetti, Alan Ameche, Lenny Moore, Art Donovan … and Jenkins, smoking a cigarette in front of P.J. Clarke’s in New York. “What’s Jenkins doing there?” a visitor asked with a chuckle. “I don’t know,” Hawkins said. “I guess because just looking at him makes me happy.”

After his transfer to Sports Illustrated (and, in the normal course of prosperity, Park Avenue, don’t you know), Dan threw much of his Scotch-and-water trade to Elaine’s (directions to the bathroom: take a right at Michael Caine) and Toots Shor’s (“the joint is quieter without the proprietor”), but Clarke’s was his home field. It was in Clarke’s where Howard Da Silva poured drinks for Ray Milland in the movie “The Lost Weekend,” and where, according to legend, with a publishing windfall, Jenkins bought a house in Maui over the telephone. “That’s not exactly true,” Bud Shrake said, “but it’s not completely false, either.”

Shrake and Jenkins had the same refined sense of mischief. “We’ve hired a new ringside photographer [for a championship fight at the Garden],” they told fabled SI managing editor Andre Laguerre. “Who?” Laguerre asked. “Frank Sinatra!”

Bud and Dan co-wrote a screenplay for Eddie Murphy’s “Beverly Hills Cop II” but were fired because it was too funny. “You know,” Jenkins told the producer, “that’s kind of what we were shooting for.” “You don’t have to be funny,” the man said. “Eddie be funny.” For the next 20 years, the co-conspirators looked across rooms at each other, pronounced “Eddie be funny” and howled.

Just behind golf and college football, Jenkins loved the movies (he was practically first in line to worship Meryl Streep). The film he prized the most, even above “Casablanca,” was “The Americanization of Emily,” which would be more surprising if everyone associated with that picture, from writer Paddy Chayefsky to actors James Garner, Julie Andrews, Melvyn Douglas and James Coburn, didn’t consider it their proudest work.

Throughout “Emily,” people keep telling Garner’s character, “The balloon’s going up any day now,” referring to D-Day. “What balloon?” he always answers absently. But when a sportswriter came upon Garner in the Bel-Air Country Club grill, and said to him, “The balloon’s going up any day now,” Garner replied delightedly, “You’re a friend of Jenkins.”

Garner claimed to have supplied Dan the title for his 1981 novel Baja Oklahoma. Jenkins and pal Willie Nelson co-wrote a song for that movie, though they were never in the same room. Nelson just took the lyrics out of Dan’s book and put them to music. Sitting next to a casting director as a line of secondary ingénues streamed past, Dan said, “I vote for her,” and she got the part. Julia Roberts.

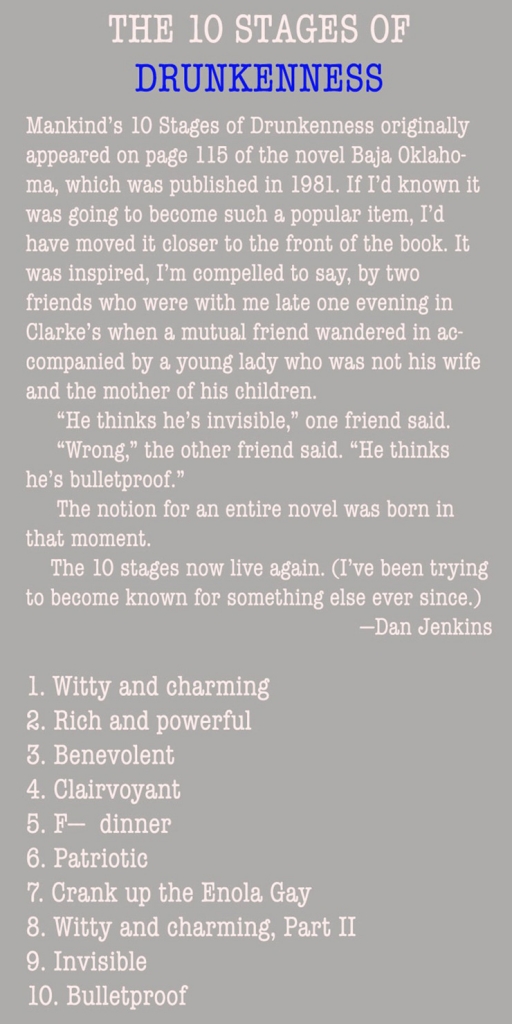

Jenkins’ 10 Stages of Drunkenness also came from Baja, popping up at Runyon’s in New York and on the walls of grog shops all across the country (plus at least one pub in the U.K.) The last two stages, nine and 10, “invisible” and “bulletproof,” were inspired by a friend of Dan’s who careened into Clarke’s one evening accompanied by a lovely-adorable not his wife or even his daughter (though she could have been). He thinks he’s invisible. No, bulletproof.

Dan’s wife was a TCU homecoming queen, June Jenkins, never June, always June Jenkins, as in “June Jenkins says hello.” Both of them had false starts in the marriage department, but then they spent almost 60 years together getting it absolutely right. There might have been a husband somewhere who loved his wife as much as Dan Jenkins loved June Jenkins, but it’s hard to imagine. As you probably know, there are chasms that come with money and Hollywood, and Dan tiptoed up to a few, but June Jenkins always saved him.

Anyway, according to the daughter among their three children, Dan’s early image of casual depravity and serial off-handedness had little basis in fact. Though never seeming to be working was an essential illusion in the sportswriting game, Sally Jenkins knew her father to be a man of “deceptive sobriety,” “veiled attentiveness to family” and a “sly conscientiousness at his work.”

She was the one who followed him into the breach, to Sports Illustrated, then the Washington Post, where for 18 years she has written a lyrical column with a Jenkins edge. Under the email heading Term Themes, Dan took to shooting her best columns, meaning just about all of them, to a colleague (probably more than one colleague). “Read Sally Jenkins today,” he’d say, “and try not to laugh or cry. I couldn’t.”

Sally, Marty and Danny were his heroes.

Dan with his children Sally and Marty. Dom Furore

• • •

Presumably owing to Semi-Tough’s notoriety as a book, a Burt Reynolds movie and nearly a David Merrick Broadway musical, Sports Illustrated removed Dan from college football and relocated him in the NFL, a colossal blunder. Like a large slice of pro football’s audience, Dan needed an economic interest to suffer the games. And the more he bet, the more prominent the officials, the “Zebras,” became in his narratives. Inevitably Dan clashed with a new managing editor, Gil Rogin, who was not Andre Laguerre, and in 1985 Jenkins came to Golf Digest.

It was probably just as well. SI had become heavily populated with Dan Jenkins impersonators, some of them 2 and 3 degrees removed. Curry Kirkpatrick was trying to do Jenkins. Barry McDermott was trying to do Curry Kirkpatrick trying to do Jenkins. The problem, of course, was there was only one Jenkins.

“If you want to put golf back on the front pages again and you don’t have a Bobby Jones or a Francis Ouimet handy, here’s what you do: You send an ageing Jack Nicklaus out in the last round of the Masters and let him kill more foreigners than a general named Eisenhower.”

Dan always rooted for the best stories, which usually meant the best players (the real reason he loved Hogan might have been that Ben once saved him from having to write about Masters runner-up Skee Riegel), though some of golf’s journeymen, the ones with wit and perspicacity, like Ed Sneed, became trusted sources. Dave Marr, a PGA champion but not an all-time great, was Dan’s No. 1 draft choice for dinner.

As truthfully tough as Jenkins could be in print, he had a heart. Settling into a steamy Medinah press tent under a killer Monday deadline, he had just begun to bang out the dull tale of Lou Graham’s playoff victory over John Mahaffey in the 1975 Open when tapped on the shoulder, Jenkins spun around to find Graham’s wife, Patsy. “Be nice, Dan,” she beseeched him softly. “He’s really a good guy.” So charmed was Jenkins, he left out a voice he had overheard in the gallery, whispering, “Where does Lou Graham get all those faded shirts?”

Tiger Woods didn’t want to know Jenkins. “We have nothing to gain,” agent Mark Steinberg said, the dumbest thing any agent ever said. During the 2006 Open Championship at Hoylake, Woods’ second-most-amazing tour de force, coach Hank Haney was staying at the Golf Digest house. Every night, after hitting balls post-round, Tiger dropped Haney off and never came in. Perhaps just that squandered opportunity of a beer with Jenkins, or at least the astonishing cluelessness it represented, was the real first cough by Ali MacGraw in “Love Story” (as it preceded Tiger’s come-from-ahead loss to Y.E. Yang in the 2009 PGA). At Woods’ peak, Jenkins wrote, “Only two things can stop him: injury or a bad marriage.” Birdie, and birdie.

Presidents of the United States did want to know Jenkins, particularly George Herbert Walker Bush, Dan’s sometime golfing partner. Whenever the presidential helicopter overflew a course, Bush telephoned Jenkins for a rundown. George and “Bar,” June Jenkins and Dan, stayed in each others’ homes. Dan called Camp David “my favourite hotel.” Driving Jenkins around in a golf cart there one daybreak, “41” (as Bush signed his letters to Dan) said, “See that porch bench in front of Holly Cabin? You might want to sit on it for a minute. That’s where Roosevelt and Churchill planned the D-Day invasion.”

When Jenkins sent Bush a friend’s book, the president wrote the author a note of thanks that began, “Any friend of Dan Jenkins … has to be investigated by the Secret Service.”

Dan’s final tally of majors would be 63 U.S. Opens, 45 Open Championships, 56 PGAs and 68 Masters, which, as he said, “is a lot of peach cobbler no matter how you slice it.” In his 80s, he reinvented himself as “The Ancient Twitterer,” which made sense. Dan was always faster on the draw than 140 characters. Thirty years apart, he thought Greg Norman looked “like the guy they always send after James Bond,” and Danny Willett looked “like a guy who could have driven the getaway car for Bonnie and Clyde.”

Giving up essays for tweets left him more time to talk writing with the young writers who queued up at his desk in the press rooms, saying stumbling things like “I’ve always wanted to be like you.” To which he might reply, “Hungover?” But then he’d answer seriously and at whatever length they preferred:

Dom Furore

“My advice doesn’t change with electricity,” he said. “Be accurate first, then entertain if it comes naturally. Never sell out a fact for a gag. Your job is to inform above all else. Know what to leave out. Don’t try to force-feed an anecdote if it doesn’t fit your piece, no matter how much it amuses you. Save it for another time. Have a conviction about what you cover. Read all the good writers that came before you and made the profession worth being part of—Lardner, Smith, Runyon, etc. Don’t just cover a beat, care-take it. Keep in mind you know more about the subject than your readers or editors. You’re close to it, they aren’t. I think I can say in all honesty that I’ve never written a sentence I didn’t believe, even if it happened to be funny.”

In 2012, Jenkins became the first living sportswriter of three (Bernard Darwin of The Times of London and Herbert Warren Wind of The New Yorker the others) to be stuffed and mounted at the World Golf Hall of Fame. “I’d follow [fellow Fort Worthers] Hogan and Nelson anywhere,” he said. “I went back and looked up everybody who’s in it and did some statistics. It turns out that I have known 95 of these people when they were living. I’ve written stories about 73 of them. I’ve had cocktails and drinks with 47 of them. And I played golf with 24 of them.”

During the Oakmont Open of 2016, as Arnold Palmer was failing but too considerate not to receive a sportswriter in his Latrobe office, Arnold said, “Before we start, let me ask you something. How’s Dan?”

One by one then, of course, Jenkins began to lose his friends.

In 2009, at 77, Bud Shrake.

Term Themes: “Bud drifted downriver at 2:45 this morning. His son Ben, a great kid, was with him at the end. He took part of my life with him. We’d been close since junior high school. But I’ll catch up with him one of these days—and we’ll be laughing at something. Bud will be buried next to [former Texas governor] Ann Richards in Austin state cemetery. Bud and Ann, who were great old Austin friends, and the last loves of each others’ lives, had arranged it a long time ago.”

(Once, Bud sneaked a news-magazine guy past a press secretary into the statehouse for dinner with Gov. Richards. “How do I refer to Bud in my story,” the man asked her during dessert. She looked at Shrake, smiled and said, “Just call him an iconoclast.”)

In 2016, at 96, Blackie Sherrod.

“My teacher,” Term Themes emailed. “Yours, too, Simon, whether you know it or not. I think you do know it. [Because I did all the driving at British Opens, he renamed me Simon after an earlier chauffeur.] I had Blackie. You had Red [Smith]. We shared them both, though, didn’t we? And Jim Murray. And Furman Bisher. Weren’t we lucky?”

Finally, on Thursday night, March 7, 2019, at 90, His Ownself.

He long ago picked out the exit music: Vera Lynn singing “We’ll meet again.” As for the carving on his stone, while he supposed he should go with something Oscar Wilde-ish like “Ah, now for the greatest adventure of them all,” the inscription he floated at the Hall was more his style: “I knew this would happen.”

What it was, was great.

Dead solid perfect.

Eddie be funny.

A news dog.

Best In Show.