Arnold Palmer would have been 89 yesterday. In The King’s memory, here’s what we learned from Arnie, on and off the course.

By Guy Yocom

Arnold Palmer didn’t leave behind a tutorial on how to live the perfect golf life. Which is just as well, because his life and golf game could never be copied by rote anyway. To play the game as well as he did and look so good doing it, to be adored so thoroughly by the public and your peers, to have a lion-like command of every environment would make a how-to useless. To live Arnold’s lifestyle, have his wealth and influence, and build such a grand family—all the while avoiding the land mines most people face—it was too fantastic to be duplicated.

Arnold might not have written down the rules, but he shed a lot of clues along the way. From golf courses, grillrooms, boardrooms, banquet halls, pressrooms, exhibition tents and on TV, he revealed how to absorb and enjoy all the benefits the game can offer. And there has been nobody better at paying it forward. Here are 10 things we learned from Arnold, on and off the course.

[divider] [/divider]

1. INVENT A SYSTEM, THEN OWN IT

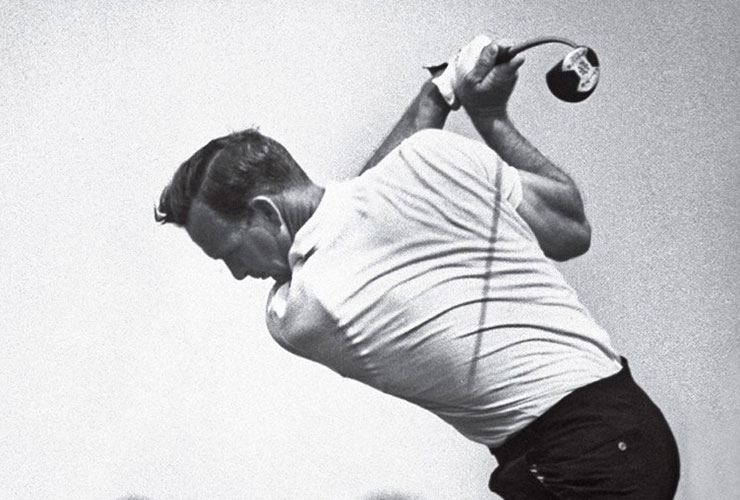

Photo by Bob Gomel/The Life Images Collection/Getty Images

A simple Palmer gem: Turn the shoulders as far as they’ll go.

“System” in golf usually describes a connect-the-dots, full-swing method. To Arnold, it meant something else. “It’s a whole way of playing,” he said.

It included the fundamentals but also the intangibles, like how far you hit each iron, your tendencies on sideslopes and downslopes, how to play in the wind or to stay calm under pressure. Arnold thought a system could partially be taught but that it mainly was self-discovered. “When you saw me gripping and regripping the club on the tee and taking a bunch of waggles, I was thinking about how I was going to play the shot,” he said. “It was part of my system and was a lot better than dwelling on how important the situation was.”

[divider] [/divider]

WATCH: GOLF DIGEST VIDEOS

[divider] [/divider]

2. ALWAYS DRESS THE PART

Around the Bay Hill Club in Orlando, Arnold was known to not wear socks with his loafers. On the flip side of this nontraditional style choice, he loathed beards, hats worn backward or indoors and shirts left untucked. He was a principled dresser and always a trendsetter. In the 1960s, he rocked a navy-blue cardigan like nobody else. In the ‘70s, he went with bat-wing collars and mod patterns, and in the ‘80s, hard-collar shirts with long plackets. Even in recent decades, his look commanded attention. He had quirks, too, favoring pink shirts and breaking out a new pair of golf shoes every week of competition. But he was basically old school. “The neatly appointed golfer,” he told Golf Digest in 2008, “is like a businessman or someone headed to church: He gives the impression he thinks the course and the people there are special.”

3. REMEMBER THE KIDS

The defining moment of a 2013 Golf Digest cover shoot with Arnold and supermodel Kate Upton had little to do with either celebrity. It was Arnold who brought the shoot to a halt while he bragged about the golf game of his granddaughter Anna Wears, then 16. How she drove it 240 yards, was breaking 80, was the most athletic of all the grandchildren, and on and on until photographer Walter Iooss Jr. had to ask Arnold to get back on his mark. Young people got Arnold’s attention. No athlete signed more autographs for young fans, endorsed more youth initiatives, put in more calls of support. A small example of his largesse: In 1984, when Arnold was turning down far more endorsements than he was accepting, he agreed to lend his name to P. Bryon Polakoff’s children’s book Arnold Palmer and the Golfin’ Dolphin. Then there’s the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children in Orlando, a highly regarded pediatric hospital that was a passion of Arnold’s since it opened in 1989. His foundation donates to many causes, but the common denominator is that they’re all for young people.

4. WALK, AND WALK SOME MORE

If for no other reason than he intensely disliked golf carts, it’s doubtful any human walked more miles on the course than Arnold. To him, it was as intrinsic to the game as swinging the club. He did it for health and enjoyment but also to help him play better. When physically-handicapped tour player Casey Martin went to court to be allowed to ride in PGA Tour events, Arnold reluctantly—but firmly—took a stand for walking. Arnold never voluntarily rode during competition as a senior and lobbied against the use of carts on the senior tour. He enjoyed incredible vitality for almost all of his 87 years. There are crazier notions than to assume walking had something to do with that.

5. A GOOD GRIP COMES FIRST

Butch Harmon has long maintained that the Vardon Trophy—a bronze-colored statue of two hands holding a club that goes to the PGA Tour player with the lowest scoring average—was modeled from a cast of Arnold’s grip. It is linear perfection, golf’s equivalent of a silhouetted Jerry West as the logo for the NBA. Arnold never denied or confirmed the rumor, but it’s true that for years, his grip was the envy of other players. Position-wise, neither hand shaded toward weak or strong, the Vs of both hands aiming at his right ear. Arnold was given the grip at age 3 by his father, along with the directive, “Don’t ever change it, boy.”

Photo by Walter Iooss Jr.

So gripping properly became second nature to Arnold, and he took immense pride in it. His grip was a perfect model for aspiring golfers a half century ago—and is to this day.

6. HIT THE BALL HARD

It started when he was 7, when a woman at Latrobe (Pa.) Country Club named Mrs. Fritz paid Arnold a nickel to drive her ball over a ditch on the sixth hole. For the next 80 years, Arnold rarely spared himself physically on any shot. The violence of his driver swing led to a balanced but contorted follow-through, and he took huge divots on iron shots. When Arnold played from a tree stump at the 1963 U.S. Open at Brookline, he sent splinters flying everywhere. He preached what he practiced: Keep the head still, turn the shoulders as far as they’ll go, and finish with the hands high above the left shoulder. But he also issued a warning: “Swinging all-out is good. Swinging beyond all-out usually leads to disaster.”

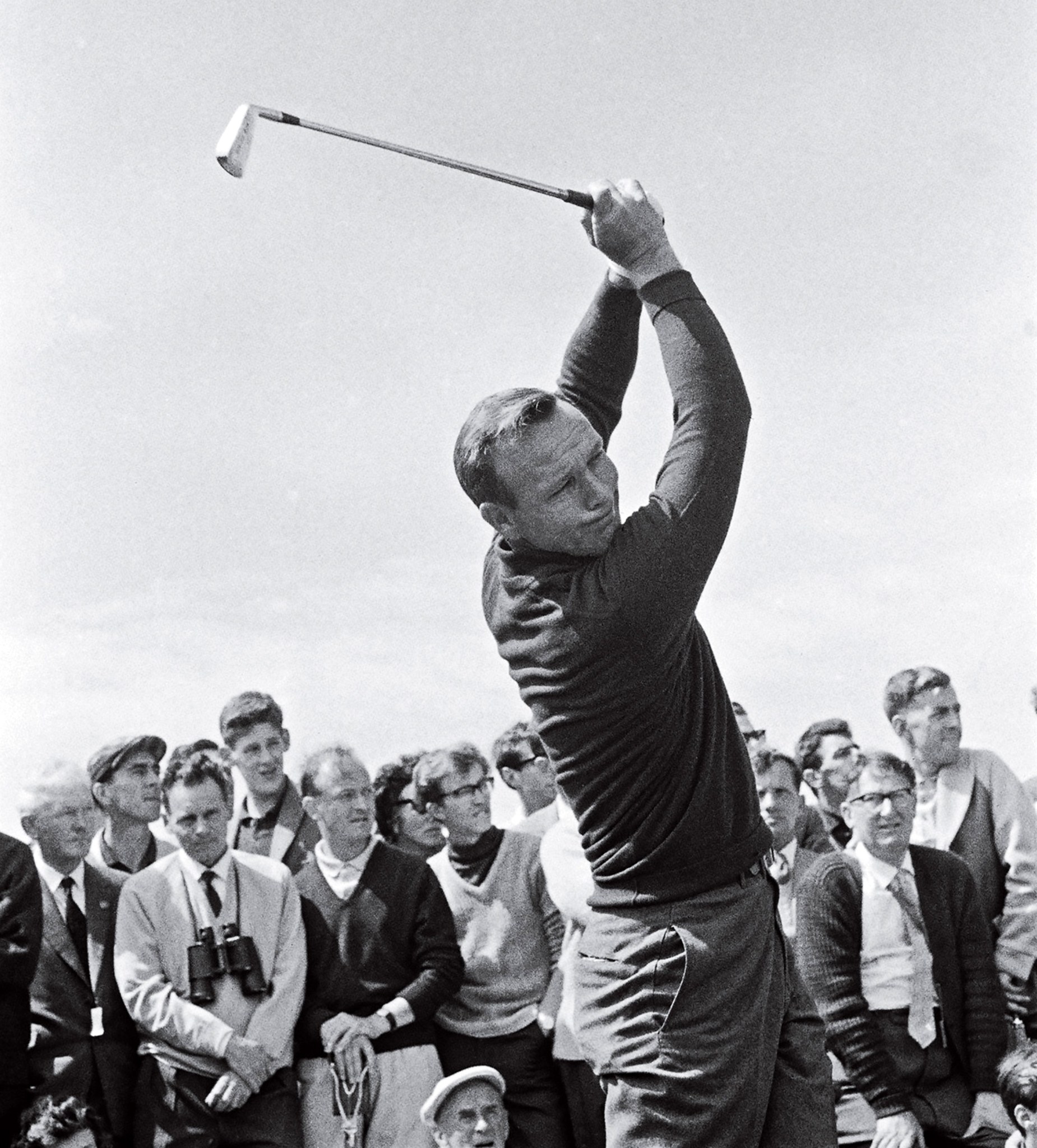

Photo by Bob Thomas/Getty Images

Legions of golfers copied Palmer’s go-for-broke style.

7. IT’S ALL ABOUT THE DRIVER

Through good times and bad, Arnold’s game was married to the driver. He hit the most famous drive in the game’s history: a Herculean bomb on the par-4 first hole at Cherry Hills outside of Denver that found the green and fueled his victory at the 1960 U.S. Open. “When I drove the ball well, I was usually tough to beat because my game flowed off that,” he said. Hundreds of his drivers, persimmon and metal, line the shelves of a modified maintenance barn at Latrobe. Arnold was a powerful driver and wanted ordinary players to taste power, too. In 2000, he controversially backed a nonconforming driver.

8. ACCEPT THE GAME’S MYSTERIES

A dark counterpoint to Arnold’s driver blast at Cherry Hills was a series of snap-hooked tee shots on the back nine at the Olympic Club in the 1966 U.S. Open, which led to an incoming 39, a blown seven-shot lead, and the title going to Billy Casper. It wasn’t the only time Arnold’s game left him. He lost the 1961 Masters to Gary Player with a double bogey on the final hole. The lesson learned is, sometimes you lose your game, and there’s little you can do about it. “When the train leaves the tracks, it’s rare you can get it back on track again,” he told Golf Digest in 2007. “It’s very hard—impossible, really—to reverse your thinking and go back to the frame of mind you were in just a couple holes before. I’m not sure we’ll ever figure out an answer.”

9. IMITATE YOUR HEROES

Arnold’s swing model when he was a boy in the 1930s was Byron Nelson, and he pored over the instruction book Byron Nelson’s Winning Golf. When he finally met Nelson, who was already famous for his proficient ball-striking, Lord Byron’s sportsmanship and unfailing politeness gave Arnold even more to imitate. Later, a generation of young golfers copied Arnold’s pants-hitching, go-for-broke style. Today, when tour pros like Phil Mickelson sign hats and programs, they often mention they’re following Arnold’s lead.

10. GET IT TO THE HOLE

“The worst thing you can do is leave a putt short,” Arnold said. In his prime, he charged them all. In the final round of the 1960 Masters, he banged a birdie putt on No. 16 off the flagstick (which at the time could be left unattended). He then rammed home a 20-footer for birdie on 17, and rapped in a four-footer for another birdie at the last to win by a shot. That’s just one example of his aggressive putting. Even when the three-footers stopped falling late in his career, he defended his style. “Get the ball to the hole no matter what,” he said. “If you do that, you’ll at least give it a chance to go in, which, if I’m not mistaken, is the object of the game.” Simple, sound advice from The King.