By John Feinstein

It started out in 2007 as a slam dunk for the PGA Tour and for Tiger Woods. It will end this coming Sunday as an embarrassment for both.

When the PGA Tour awarded what was then known as the AT&T National to the nation’s capital area, tour officials clearly expected the tournament to become one of their signature events. It would take its place alongside Jack Nicklaus’ Memorial Tournament and Arnold Palmer’s Bay Hill Invitational as an annual tribute to one of the game’s greatest players—in this case, Woods, who at 31, had already won 12 major titles and become an iconic figure worldwide.

Congressional Country Club, which had shied away from hosting the tour’s previous D.C. area tournament (which had run from 1980 to 2006 under several corporate flags), willingly signed up to host an event that Woods would be tied to and that his charitable foundation would run.

Like the Memorial and Bay Hill, the tour gave it “invitational” status, meaning only 120 players would take part and a spot in the field would be coveted. And that first year, top players indeed flocked to Washington, D.C. The premier event had 19 major champions—15 players with at least one major already to his credit and four others who would go on to win one in the near future. K.J. Choi was the inaugural champion, with Woods finishing T-6. Phil Mickelson, Woods’ longtime antagonist, played but missed the cut. The crowds were massive.

It was all good.

And seemed to be so in the few seasons after. Woods won the tournament in the third year—2009—almost matching Nicklaus, who had won the Memorial in 1977, its second year. Palmer was 50 when the Bay Hill event began and never won it, but he did make the cut in 1991 at 61.

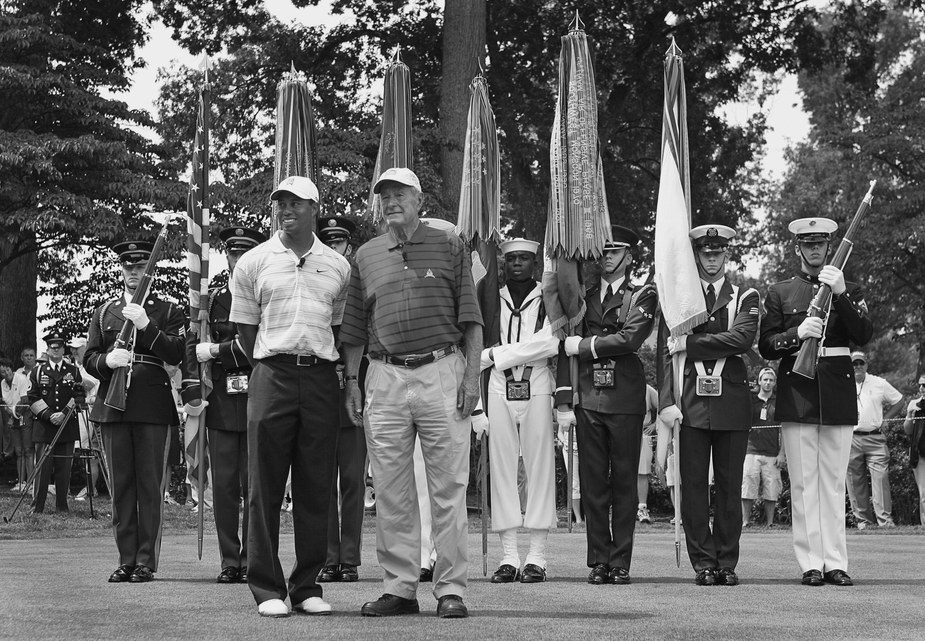

Hunter Martin/Getty Images

To help kick off the inaugural event in 2007, Woods was joined by former President George H.W. Bush.

Then came Thanksgiving 2009 and Woods’ infamous “accident” that led to scandalous headlines about his personal life. His iconic status was tarnished, which led to a series of decisions that ultimately doomed the D.C. event.

Among them was the decision by title sponsor AT&T to move away from the event in 2013 when its initial contract ran out (the company continued to sponsor the Pebble Beach stop, and subsequently picked up the title sponsorship for the Byron Nelson in Dallas).

At the same time, Congressional was also losing enthusiasm for hosting the tournament. Sure, the club liked the money—$1.5 million annually, the highest rental fee on tour—but the members (of which I am one) became less and less enamored with the idea of giving up the property for a week in mid-summer. Plus, USGA officials told the club that if it wanted to host a future U.S. Open, the annual tour event would have to go. And so Congressional agreed to pick up its three-year option after the 2014 event, but only host every other year with an absolute end to the deal after the 2020 tournament.

With that, tournament officials were now in the challenging spot of looking for a new sponsor and a new course. Quicken Loans agreed to a four-year deal just prior to the 2014 event, counting on a healthy Woods (he had won five times in 2013) to anchor the field. But injuries prevented Woods from playing in three of the next four years.

Yet that was only part of the problem: Without Congressional as a draw, and with Woods no longer king of the golf world, the number of stars in the field dwindled. What’s more, it became apparent that Woods was losing interest, too. In 2016, when Woods couldn’t play after back surgery, he made two appearances during the week, showing up for the opening and closing ceremony but flying home to Florida in between. In 2017, after his DUI arrest in May, he didn’t show up at all.

Related: The downside to Tiger-mania’s return

The tour, in an effort to save money, withdrew from Congressional after the 2016 event and moved the tournament down the street to the redesigned TPC Potomac at Avenel Farm, where it didn’t have to pay a rental fee. Formerly TPC Avenel, the course had been host of the Kemper Open beginning in 1987, much to the dismay of most players. Davis Love III had summed up the feelings of many back then when he said, “Avenel isn’t a bad golf course—unless you have to drive past Congressional to get there.” (Ironically, the tour hired Love to do a renovation in 2007 and the golf course played to much better reviews when it re-opened in 2009. Even so, it wasn’t Congressional.)

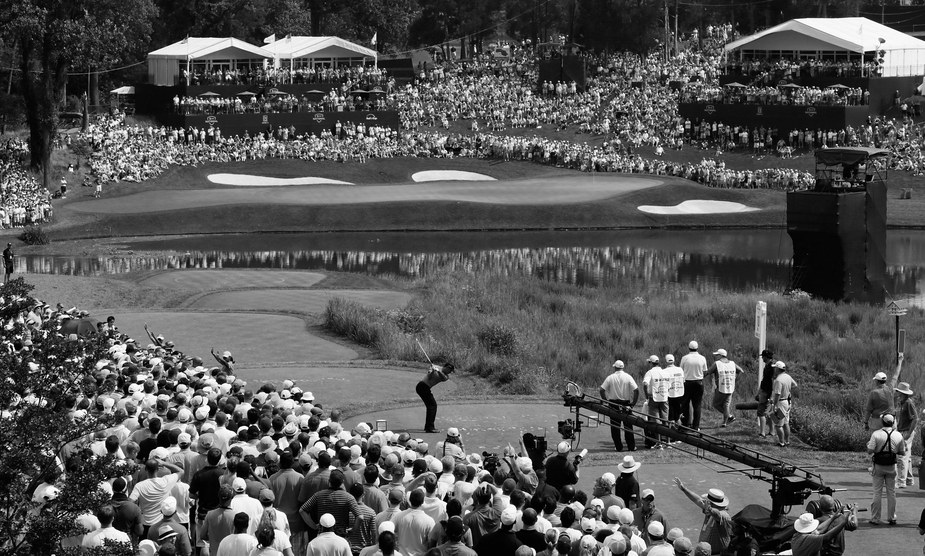

Rob Carr/Getty Images

Woods helped draw crowds to Congressional early on, but his absence due to injury in recent years made finding a new sponsor for the tournament difficult.

Even prior to the move to Avenel, however, the National was clearly in trouble. Woods made one of his many comebacks at Congressional in 2014, but wasn’t ready to play and comfortably missed the cut. His late entry helped ticket and corporate-tent sales, but once he departed Friday afternoon, the golf course felt like a ghost town over the weekend.

I wrote a column in The Washington Post that weekend in 2014 warning that the event was too dependent on Woods and wondered what would happen at the end of the Quicken Loans contract in four years. After it published, I was pilloried by officials with the Tiger Woods Foundation and by many of my colleagues in the local media.

A year later, Woods was healthy enough to compete but the tournament was played at Robert Trent Jones Golf Club way out in Virginia horse country. Even Woods’ presence didn’t help attendance much. Woods contended for two rounds, shooting 68-66 before a third-round 74 dropped him to a tie for 42nd. Troy Merritt beat new Quicken Loans client/spokesman Rickie Fowler by three strokes to win on Sunday.

By 2017, with the event back at Avenel Farms, the field looked more like a Web.com Tour event than a PGA Tour event. Fowler was there as per his Quicken Loans contract, along with four past major champions—each with one title. Attendance reflected the quality of the field, and it was apparent that Quicken Loans had no plans to renew the contract.

Even so, PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan expressed optimism last summer that a title sponsor could be secured for 2018. “I have complete confidence we’ll find a sponsor,” he said during the PGA Championship in August. “I always believe we’ll find a sponsor.”

They did … sort of.

Quicken Loans owner Dan Gilbert—who also owns the Cleveland Cavaliers—made it clear to the tour that he would only re-up as a title sponsor if his event was played in Detroit—his hometown. The tour held out until a compromise was struck: Gilbert would get his event beginning in 2019 at Detroit Golf Club if he would agree to take the title sponsorship off the tour’s hands for one last year in Washington.

In the tournament’s swansong, Woods will play this week, his lone expected start after a missed cut at the U.S. Open and before heading to the Open Championship at Carnoustie. One might have thought his apparent return to health could inspire a sponsor to jump in and take a chance on Washington, but Woods didn’t seem to really care very much if that happened. His foundation is now the beneficiary of the annual PGA Tour event played at Riviera Country Club outside Los Angeles.

The L.A. event has the kind of stability never established in Washington. It has been played at Riviera for 44 of the last 46 years, as opposed to the D.C. event which will have been held at four golf courses in 13 years, none for more than three consecutive years. Riviera is near where Woods grew up and has an established history with winners like Ben Hogan, Jimmy Demaret, Sam Snead, Arnold Palmer, Tom Watson, Billy Casper, Johnny Miller, Phil Mickelson and—most recently—Bubba Watson and Dustin Johnson. It’s a tournament that is a sure bet in a landscape that seems to change constantly.

Stan Badz/PGA

TourWoods’ Foundation now is connected with the tour’s event at Riviera Country Club outside Los Angeles.

Nicklaus and Palmer worked very hard to make their events difficult for players to say no to. They went out of their way (Nicklaus still does) to engage players throughout the week, whether they were playing or not. Woods never showed that kind of enthusiasm in Washington. He did the absolute minimum, thinking—correctly to some degree—that as long as he could play, the tournament would stay afloat.

In 2015, after he had shot 66 in the second round at the Robert Trent Jones course, he sat in the back of the players dining area by himself at the height of the post-morning-wave lunch hour. The room was packed. When Woods finished eating, he walked the length of the room, looking straight ahead and didn’t pause to greet anyone.

“Our congenial host,” said one veteran player as Woods walked past the table where he was seated.

The next two years, Woods couldn’t play. He’ll be back this year. Perhaps he’ll win this coming Sunday. It would make for a bittersweet farewell.