From the archive (March 1991): ‘I want to be the next dominant player’

By Jaime Diaz

In celebration of Golf Digest’s 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published. Each entry includes an introduction that celebrates the author or puts in context the story.

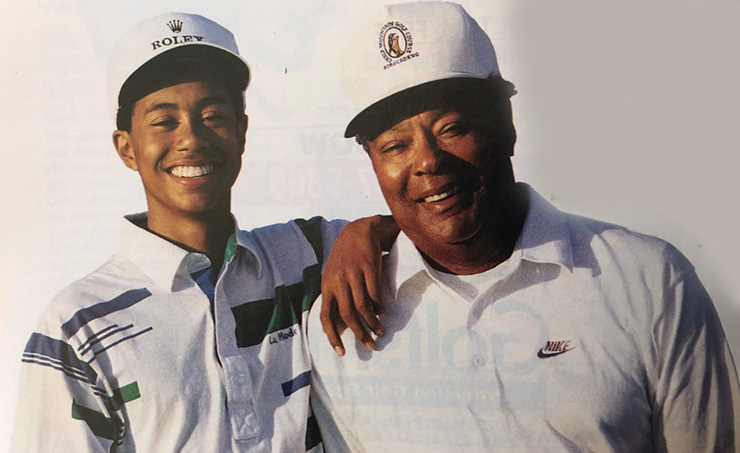

Tiger Woods’ first appearance in Golf Digest came in 1981, when the phenom was 5 years old, tall as a ball washer and weighed 44 pounds. He was said to be shooting in the 90s on a regulation course and had appeared on network television with Bob Hope. Tiger’s father was described as a retired Army colonel, a McDonnell Douglas contracts administrator and a 3-handicap. “The kid’s not exceptional,” his pro, Rudy Duran, was quoted as saying. “He’s way beyond that.”

Our next encounter was in 1987, when Tiger was 11 and entered the magazine’s first Armchair Architect contest with a drawing of his dream hole—a U-shape, double-dogleg par 5 with an island tee and island green. He didn’t win the contest, but we eventually noticed him racking up junior victories, ranked him America’s third-best junior amateur of 1990, and dispatched senior writer Jaime Diaz to profile Tiger at age 14 in late 1990 for the March 1991 issue (below). His first appearance on a cover of Golf Digest was in November 1994 as a model for an instruction story on power. His second cover was two years later when he turned pro, with the headline, “Is This Kid Superman?” Frank Hannigan writing inside tried to temper the growing fervor: “Tiger Woods is a joy to watch, and he may very well achieve his goal of becoming the best player in the world. But there is a need for perspective. There are a lot of missed putts between desire and fruition.”

Before we get ahead of ourselves, which is hard not to do with Tiger Woods, return with us now to yesterday, when the young man was only 14 and the dream was still new. —Jerry Tarde

For someone named Tiger, the kid didn’t seem very predatory. Seventeen holes with his dad and a sportswriter had produced no blood—in fact, not even a bet. The only thing remotely competitive was the annoying way the old man kept jingling change when the kid got ready to putt.

But Eldrick (Tiger) Woods is used to winning. Finally, on the 18th tee of Coto de Caza, an arduous Southern California test, he can’t resist.

“Play you for some ABC gum,” Tiger says to the sportswriter, who, extremely thankful that his only losses to this point have been four golf balls, vacantly accepts.

Woods rhythmically settles his lithe, 5-foot-11, 138-pound frame over his ball, and with a fluid action that mixes some Davis Love III power with a smooth dollop of Al Geiberger tempo, belts a 270-yard drive down the middle. He follows with a 9-iron to 10 feet and, naturally, makes the putt.

“Where do I find ABC gum?” asks the loser.

“In your mouth,” says Woods, rolling his eyes at the lameness of his victim. “Already Been Chewed.”

As Woods cackles at the schoolboy joke, the sportswriter remembers what he has kept forgetting all afternoon. The supremely talented golfer who has been busting huge 1-irons and sucking back approach shots all day is only 14 years old.

Very simply, Tiger (Please Don’t Call Me Eldrick) Woods of Cypress, Calif., is one of the most precocious lights on the American golf scene. The prodigy has accomplished more at his age than Bobby Jones, Jack Nicklaus and Lanny Wadkins did as wunderkinder, and even more than junior stars like Eddie Pearce and Tracy Phillips, who reached their peaks in high school before fading from the arena. If Woods can maintain the rate of his rise—and “if” must always be emphasized when projecting golfing genius—he could develop into one of the game’s finer players.

“That’s what I want,” Woods says. “I want to be the next dominant player. I want to go to college, turn pro and tear it up on the tour. I want to win more majors than anybody ever has.”

“The game has never seemed hard,” says Woods, who speaks with an unaffected openness about his prowess. “I don’t know why, but I’ve always been good.”

Remarkable words, but Woods has a remarkable history. The son of a black father and Thai mother, he has been a phenomenon since the age of 3, when he shot 48 for nine holes on the regulation-length Navy Golf Club near his home. His prowess got him on “The Mike Douglas Show,” where, still wearing training pants, he competed with Bob Hope in a putting contest. At age 5, Tiger was featured on the TV show, “That’s Incredible!” and was the subject of an article in this magazine (November 1981). At 8, he was the club champion on the 2,156-yard, nine-hole Heartwell Golf Park. In 1981, he won the first of five Optimist Junior World age-group championships. By the time he was 13, he has made five holes-in-one and played an exhibition with Sam Snead.

“The game has never seemed hard,” says Woods, who speaks with an unaffected openness about his prowess. “I don’t know why, but I’ve always been good.”

And getting better. Last year, in the midst of a growth spurt that saw him sprout nearly seven inches and gain 25 pounds, Woods had perhaps the most impressive year a 14-year-old has had since Bobby Jones won the Georgia State Amateur and went to the third round of the U.S. Amateur.

In a three-week period last July, Woods won a local city junior championship, took the 13-14-year-old division title in the World Junior, then grabbed the Big I Insurance Classic in Fort Worth.

Woods’ bid to become the youngest player, and first black, ever to win the USGA Junior Championship fell short when he lost in the semifinals at Lake Merced Country Club in San Francisco. And the week after the Big I, he finished second at the United Van Lines PGA Junior Championship at PGA National. The victor there with a 63 in the last round was that other youthful phenomenon making a big noise, 17-year-old Chris Couch, possibly the youngest player ever to qualify for a PGA Tour event.

Woods tried to get his revenge on his nemesis at the year-ending Orange Bowl in Coral Gables, Fla., Couch’s home turf. Woods was two shots back going into the final round. But on Dec. 30, his 15th birthday, he blew up with a 78 to fall to sixth place, and Couch won. The hotly contested battle for consensus junior player of the year also went to Couch, who moves out of the junior class on his 18thbirthday in 1991, when he begins classes at the University of Florida.

“It was a learning experience,” says Tiger’s father, Earl Woods, who has developed his own brand of “tough love” to help nurture his son’s talents. “We had a debriefing. This is what I learned in Vietnam—you have a debriefing after a battle. He learned that he can’t win everything, even though he may want to. Right now it’s important for him to enjoy. When he’s 17, I fully expect him to win everything. But not now.”

It’s Earl Woods’ passion to manage a balance between Tiger’s enjoyment of the game and his desire to win. A former contracts administrator for McDonnell Douglas, the elder Woods is a retired lieutenant colonel in the Army. In talking about his son, he usually effects the role of pacifist in the warfare of the fairways.

“I’m just there to make sure he keeps things in perspective,” Earl says as he sits in the living room of his suburban home. “Tiger has such a high competitive drive to win and to score, it’s a constant fight for me to get him to go out and just have fun playing a round of golf.”

To prevent the burnout that can attack golf prodigies, Earl and his wife, Kultida, have made sure their son gives as much attention to academics as to golf. Tiger, now a freshman at Western High School, has kept up a 3.5 grade average. He played in a limited schedule of about 30 tournaments in 1990.

Then again, competition is in Tiger Woods’ blood, in large part because of his father. Earl Woods was the first black to play baseball in the Big Eight Conference, at Kansas State. After a shoulder injury, he chose the military over professional baseball. He was drawn to the front lines, and in Vietnam he befriended a Vietnamese soldier nicknamed Tiger.

“That guy was so brave, such a bitch in the field, I decided my next son’s nickname would be Tiger,” Earl says.

That son took to golf with big-game ferocity before he was a year old. At 6 months, Tiger would sit in a high chair and watch his 3-handicap dad hit balls into a net in the garage. At 11 months, he was imitating his father by hitting a tennis ball down the hall with a vacuum-cleaner hose.

It wasn’t long before his father was taking Tiger along on 18-hole rounds at the Navy Club. By age 4, Tiger was carrying his own bag at Heartwell.

“My view is, God gave me a gift, and he trusted me to take care of it,” Earl says.

That means ensuring that his son can take care of himself. He sadly recounts the story of Tiger’s first day of school, where, as the only black student, he was tied to a tree and called names by a group of older children. His son has also felt the specter of racism at some of the country clubs where junior tournaments have been played.

“You can feel it—I call it The Look,” Tiger says. “It makes you uncomfortable, like someone is saying something without saying it. It makes me want to play even better. That’s the way I am. Little things like that motivate me.”

“This isn’t a very nice world sometimes,” Earl says. “I’ve used psychological techniques, things I learned in prisoner interrogations, to toughen Tiger up. It’s to prepare him, not to use as an offensive tactic. I’m not trying to create a little monster.”

On the golf course, the techniques take the form of Earl placing his shadow in his son’s putting line, coughing in the middle of his stroke, or talking annoyingly about the out-of-bounds on the left.

“I tell Tiger, ‘When you are ahead, don’t take it easy, kill them,’ ” his mother says. “ ‘After the finish, then be a sportsman.’ ”

Tiger is used to his father’s testing and even welcomes it. At Coto de Caza, the interplay is comfortable and happy, and Tiger has fun despite some missed putts.

“You can’t get to me, Pop,” he says as Earl jingles change while Tiger is over an approach shot. On the next hole, as the elder Woods prepares for a delicate cut shot over a bunker, Tiger says just loudly enough: “Watch. He always hits these shots fat.” When Earl chunks his shot into the sand, there is a second of silence before the two bust out laughing.

Tiger also has a close relationship with his mother. A friendly, energized woman whose accented English comes in torrents when the subject is her child, Kultida is proud to have spent countless afternoons driving her son to the golf course, then walking and keeping score for Tiger.

Woods was a celebrity by age 5 when he appeared on the “Mike Douglas Show”.

Kultida, who thought up the name Eldrick, keeps a shrine to her son’s career. She still has the shoes she glued spikes to when he was 4, and she has filled four scrapbooks with clippings, landmark scorecards (including the first time he beat his father, in 1982) and every report card he ever brought home. Tiger’s trophies fill the living room, and there are three boxes full in the garage.

Although it is Kultida Woods who has made sure Tiger attends to his homework before golf, she is in her own way every bit as competitive as her husband.

“I tell Tiger, ‘When you are ahead, don’t take it easy, kill them,’ ” she says. “ ‘After the finish, then be a sportsman.’ ”

Tiger has learned well. “I love competition,” he says. “I love to play in tournaments, especially against older kids.”

Though Woods has thrived on a giant-killer mentality, he is also making the difficult adjustment to being the giant. Last year was a psychological minefield for a young man facing his first national tournaments.

Woods, self-deprecating as he is brash, has a vivid memory of the gnawing nervousness he felt the morning of the final round of the Big I. During a dinner at an all-you-can-eat steak house in which he returned to the buffet line as least five times, Woods alternated between mouthfuls of food and youthful hyperbole in an animated retelling of the experience.

“I was in the shower in my hotel room, and I couldn’t pick up the bar of soap,” says Woods, shaking his head and smiling. “I was choking in the shower. And I’m thinking, How am I going to handle this? On the first tee, I’m 100-percent nervous. I was choking so much, I was laughing. My eyes were looking at trees. I couldn’t focus on the fairway. I scraped it around for six holes, then on 7, I choked so hard on this 4-iron. I hit it beyond right.”

After recovering to within eight feet of the pin, his panic gave way to a sudden, mysterious calm that champions sometimes admit to.

“I knew I had to make that putt. I told myself, If you make this putt, you win. This is the turning point. And, I just felt myself slow down, like the game was easy again. I knocked it in, and I busted the next drive. And I won.”

Those who have seen Woods in competition are struck by the youngster’s poise even more than his ball-striking ability.

“Tiger’s got an aura about him, that you see in very few kids,” says Chris Haack, assistant executive director of the American Junior Golf Association. “Besides having a great swing, he shows very little emotion on the golf course. He’s got the killer instinct, and he knows how to think his way around the golf course. You just don’t see all those things in juniors, let alone a 14-year-old.”

Chris Couch, who once lost a four-ball match against Woods in the Canon Cup, has plenty of respect for his younger counterpart.

“I was real motivated when I played against Tiger because, no matter how young he is, I could see his ability,” Couch says. “I think he has the best chance to be the best junior in the country this year.”

Tommy Moore, a PGA Tour player who was paired with Woods in the third round of the Big I, was similarly impressed watching Woods shoot a 69 that beat 15 of the 21 pros who played with the juniors.

“This kid has a lot of talent, just a ton,” says Moore, who shot 72 the day he played with Woods. “He’s very long. He has a very clean, simple technique that to me was superior to the other juniors I saw. He’s got an unbelievably soft touch. The only thing about him that was 14 was his appearance.”

But Moore, Golf Digest’s No. 1-ranked junior golfer in 1980, remembers several contemporaries from his youth who never fulfilled their promise.

“You can’t ‘crystal ball’ what you think Tiger can do,” Moore says. “Yes, he’s good enough to play on the Division I college level right now, but is he going to be a great collegiate player? You can’t say that. Is he going to be a great pro? You really can’t say that.

“My advice for Tiger would be, ‘Don’t get caught up in what other people are saying.’ People are going to say, ‘Wow! You shot 63 at 14, imagine what you will shoot when you’re 18!’ But golf doesn’t work like that. Right now, the only thing he should be concerned with is enjoying his success and trying to keep improving every day. Because the enjoyment tends to lessen, and the improvements get harder and harder.”

The hardening of Tiger Woods is well underway, but on the outside, he’s still a teenager with an impish humour and a soft side that can melt even his tough old man. Earl Woods’ voice get shaky when he remembers how his son reacted to losing, 3 to 2, to Dennis Hillman at the USGA Junior.

“We got in the car, and Tiger stayed quiet for a little while,” Earl says. “Then he reached over, hugged me and said, ‘Pop, I love you.’ That made the whole thing worthwhile for me. I’m very proud that Tiger is a better person than he is a golfer.”

The feeling seems to be mutual. “Earl is the coolest guy I know,” Tiger says. “He doesn’t live through me, which is what some parents do. He might watch me play, but I don’t think about him on the golf course. I just think about me. It’s all me.”

Woods knows it’s a selfish game, but he is not full of himself. He is constantly evaluating his weaknesses. Last year, he began an exercise program he learned in this magazine (“Winter Exercise for a Spring Payoff,” January 1990), and by December was up to 138 pounds, and 40 yards longer off the tee. He seems more interested in his few losses than his many victories, instinctively knowing that the lessons he takes from failures will ultimately be his most valuable. He has a vivid memory of how humble he felt while Couch was making seven birdies in the first 13 holes at the PGA.

“I was playing awesome, but I was getting wasted,” Tiger says. “I hate to lose, but in golf everybody loses because it’s so hard mentally. Sometimes you get so nervous. I like the feeling of trying my hardest under pressure, it’s when I play my best. But it’s so intense, it’s hard to describe. It feels like a lion is tearing at my heart.”

It’s the sensation that makes some prodigies disappear. But so far, it’s only caused the one called Tiger to live up to his name.