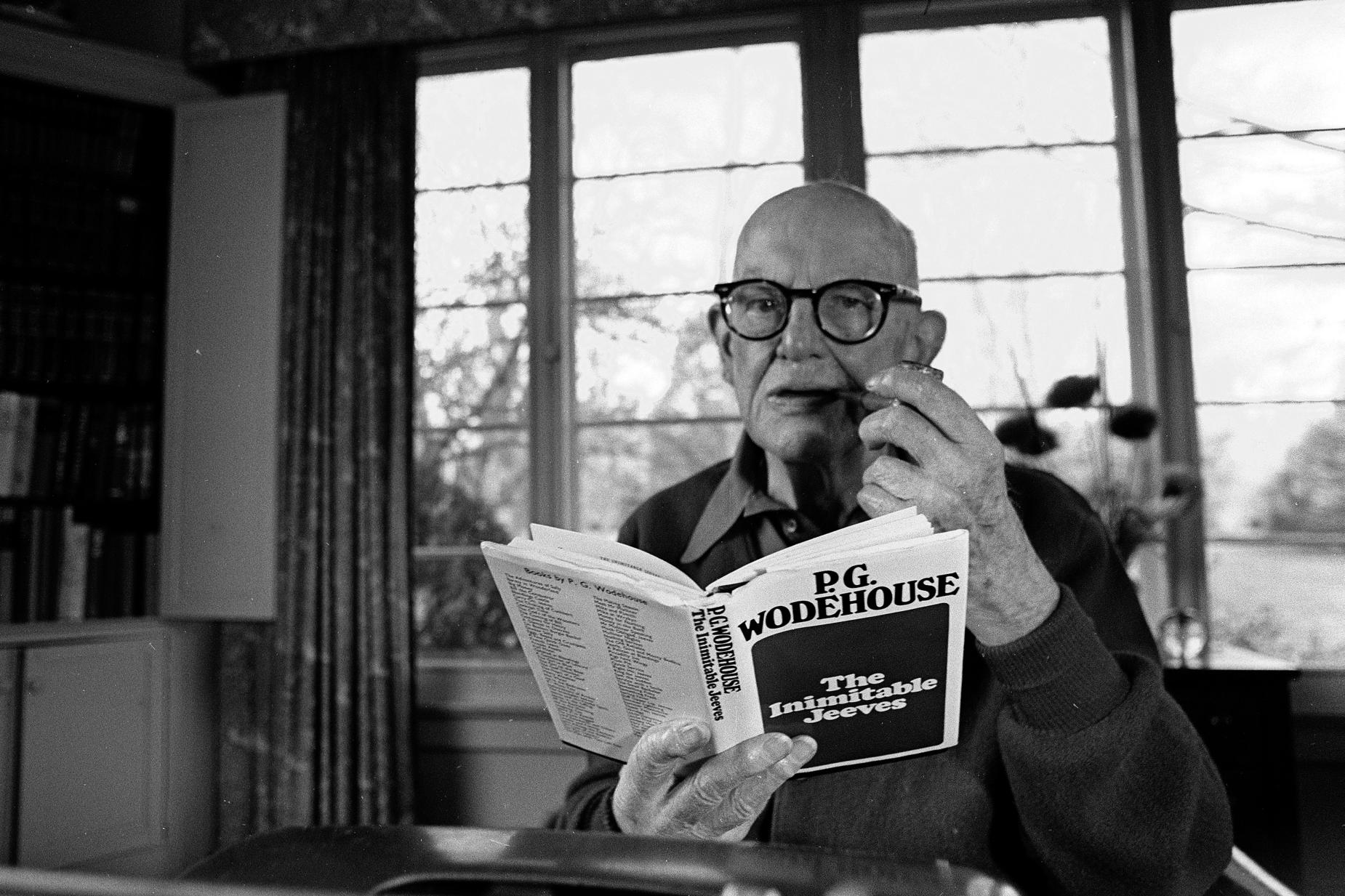

Michael Brennan

In celebration of Golf Digest’s 70th anniversary, we’re revisiting the best literature and journalism we’ve ever published.

By Peter Andrews

One of the first books I ever read about golf was an anthology by the British author P.G. Wodehouse. The collection was named for its first entry: “The Clicking of Cuthbert.” It begins with a young man entering the clubhouse, flinging his bag on the floor and pressing the bell on the wall for drink service. When the waiter enters the room, the young man tells him to take away the clubs and give them to a caddie. This early in the reading, Wodehouse reveals his genius:

“Across the room the Oldest Member gazed at him with a grave sadness through the smoke of his pipe. His eye was deep and dreamy—the eye of a man who, as the poet says, has seen Golf steadily and seen it whole. ‘You are giving up golf?’ he said.”

And thus begins another inescapable tale of human frailty and passion told with an English accent and the singular wit of the Master. What Dan Jenkins did for Texas golf, Wodehouse had already staked out the turf for the British Empire. During most of the 20th Century, he was one of the most widely read humorists in the world. A banker by day, he became a writing legend at night. His characters like Jeeves, Bertie Wooster, Lord Emsworth and the Oldest Member defined Edwardian England and beyond. Fortunately for us golfers, he wrote with a knowing pen about the game we love. If you haven’t read him, Peter Andrews’ appreciation, published in May 1994, is a good place to start. —Jerry Tarde

***

Funny golf short stories are as rare as baseball movies that make sense. In the history of the English language, there have been perhaps 40. The good news is they are easy to find because P.G. Wodehouse wrote 35 of them. There have been a number of nonfiction writers on golf who can be called great, but when it comes to fiction, there is Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, and you search the horizon in vain for his equal.

Wodehouse golf stories still make us laugh after all these years, which should come as no particular surprise, for he is the most popular writer of light fiction ever known. He is read in every language that has a discernible grammar.

Among his more than 300 short stories are a clutch of golf tales, most of which were written in the 1920s. Like a Mozart sonata, each one is a tiny miracle gone in a second, leaving behind a line that lingers sweetly in the memory.

The beginning of his first golf story, “Archibald’s Benefit,” published in 1910, sets the scene for all that is to follow: “Archibald Mealing was one of those golfers in whom desire outruns performance.” Here is an elemental character we all know: Hamlet foozling in the rough, Oedipus going way out-of-bounds, King Lear losing his ball on the blasted heath.

In story after story, Wodehouse returns to his sportive theme, bringing us characters irretrievably linked to golf. There is the profuse Agnes Flack, the low-handicap women’s champion whose voice sounds “like the down express letting off steam at a level crossing.” When she refuses a marriage proposal by Sidney McMurdo on the sixth green, “the distant rumblings of her mirth were plainly heard in the clubhouse locker room, causing two who were afraid of thunderstorms to cancel their match.”

In a Wodehouse golf story, no emotion runs deeper than the game. When Peter Willard and James Todd play a match to win the hand of Grace Forrester, the Oldest Member, who relates most of the stories, notes sagely: “Love is a fever which, so to speak, drives off without wasting time on the address.”

As in golf, the course of true love does not always run smooth. “There is nothing sadder in this life,” the Oldest Member notes, “than the spectacle of a husband and wife with practically equal handicaps drifting apart.”

There can be disappointment. Mortimer Sturgis marries Mabel Somerset under the impression she is a golfer when, in fact, she plays croquet. Their honeymoon, spent viewing the antiquities of Rome, is something of a frost. Mortimer’s only thought when looking at the ruins of the Coliseum is to speculate “whether Abe Mitchell would use a full brassie to carry it.”

Sometimes there is even violence. When the chatty fiancé of Celia Tennant talks during her backswing, she bashes him with a niblick. The Oldest Member approves: “If the thing was to be done at all, it was unquestionably a niblick shot.”

But there is also redemption. Rodney Spelvin, who had misspent his youth as a vers libre poet, is cleansed of his wastrel ways by the purity of golf. Hitting a crisp baffy to the green will do that for a man.

Golf is the eternal metaphor. To describe the sweetness of one of his heroines, P.G. writes, “She was one of those rose-leaf girls with big blue eyes to whom good men instinctively want to give a stroke a hole and on whom bad men automatically want to prey.”

ALL NATURE SHOUTED ‘FORE’

Latter-day critics were forever trying to connect Wodehouse to a real-time in a real world. Usually, they referred to his stories as “Edwardian.” Which made him frantic. Wodehouse created his own world in which time had no function. Wodehouse never tires because he never dates. Try to read other 50-year-old funny stories. Most of them are as embarrassing as watching your Uncle Fred get lit at a party trying to put on a chicken suit. An extravagant admirer, Evelyn Waugh, once wrote: “For Mr. Wodehouse there has been no fall of man. … His characters have never tasted the forbidden fruit.”

Wodehouse began one story, “The Heart of a Goof,” by describing the golfer’s Eden. “It was a morning when all nature shouted ‘Fore.’ The breeze, as it blew gently up from the valley, seemed to bring a message of hope and cheer, whispering of chip shots holed and brassies landing squarely on the meat.”

Earthly Paradise. Wodehouse characters did many dopey things, but they were never foolish enough to cross up the Lord and get their playing privileges revoked. Except for The Wrecking Crew, a doddering group of octogenarians who never let anyone play through, his stories are bathed in external sunlight. Even ex-convicts hurry back to reunions at Sing Sing full of goof spirits and bonhomie. And there are golf lessons great and small to be learned. Wallace Chesney is a hopeless duffer until he buys a pair of magical plus fours. His handicap turns to scratch, but he becomes mean and overbearing in the process. When the plus fours are burned, his game goes, but he is once again a good companion, for Wallace learns the great truth, “It is better to travel hopefully than to arrive.”

OF BARONETS AND ECCENTRICS

Wodehouse, or Plum, as he was called by his family and friends, slipped into the world as quietly as Cuthbert Banks trying to be inconspicuous at a tea party. Wodehouse was born on Oct. 15, 1881, at 1 Vale Place, Epsom Road, Guildford, England, “before you could boil a kettle,” said one biographer. He came from good stock. If one looked hard enough, and he never did, there were baronets in the Wodehouse ancestry as well as a dim line going back to a sister of Anne Boleyn. His father was a Civil Service official stationed in Hong Kong and something of an eccentric. One hot day he bet he could walk around the island, and he suffered sunstroke of such severity he was left a semi-invalid for the rest of his life.

There were three Wodehouse boys who, frequently separated from their parents, were passed around among a succession of aunts. Charles Dickens would have written a trilogy about such a deprived adolescence, but that was not the Wodehouse way. “My feeling,” he said, “is that it was very decent of those aunts to put up with three small boys for all those years.”

The great ones start young. Plum wrote his first story at the age of 7. He was not, however, a gifted student, preferring athletics to academics. A large boy, he was a good forward at rugby, akin to a lineman in football, and bowled a hard ball at cricket. He rather fancied himself as a boxer, but his eyesight was poor, and he got hit more often than he liked. The school headmaster, Dr. A.H. Gilkes, was a stern pedagogue given to saying things like, “Cicero had a large plant of conceit growing in his heart, and he watered it every day.” He considered Plum to be a pleasant boy, but something of a ditherer. Upon graduation, there was not enough money for Plum to go to Oxford, and he was ticketed for the purple of commerce.

At 19, he went to work for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in London, where he spent two dreary years licking stamps and losing the mail. He also started writing in every spare moment. He picked up what he called a “blizzard” of rejection slips but managed to sell perhaps 80 articles and stories to publications ranging from Public School Magazine to Sandow’s Physical Culture Magazine. To the great relief of the banking industry, he decided to devote himself entirely to the craft of writing.

A GREAT FLOOD

Writing alternatively in England and America, stories, books, articles, poems and stage works flew from Wodehouse’s pen, not always under his own name. He also wrote as J. Plum, P. Brook-Haven, Pelham Grenville, C.P. West, and J. William Walker, among others. For a while he was deeply involved in the Broadway theater, and in 1917, six Wodehouse shows opened in the same season. He wrote the lyrics to “Kitty Darlin’ ” and “The Riviera Girl,” the lyrics for “Have a Heart,” “Oh Boy!” and “Leave it to Jane,” as well as sketches for “Miss 1917.” In the same year, in addition to publishing short stories for The Strand in England and The Saturday Evening Post in America, he also published two novels, Piccadilly Jim and Easy Money.

If this seems like a lot, it must be remembered that Wodehouse came from the 19th-century workhouse tradition when writers were expected to write, not appear on talk shows.

Wodehouse’s work as a lyricist and book writer for the musical stage is now largely forgotten. In his time, however, he was a true revolutionary. The American composer Richard Rodgers wrote, “Before Larry Hart, only P.G. Wodehouse had made any real assault on the intelligence of the song-listening public.” Until then, American musicals bore heavily on the ornate European operetta tradition of massed choruses and carloads of scenery. Wodehouse introduced “situation comedy” before television ever heard of it and cut through the treacle with rhymes like this one about Cleopatra:

“She gave those poor Egyptian ginks

Something else to watch besides the sphinx.”

It might not sound like much now, but to audiences used to stuff like, “Give me your hand/You’ll understand/We’re off to slumberland,” it was pretty spiffy stuff.

Almost as an afterthought, a very carefully worked out afterthought, Wodehouse created his two matchless creations: Bertie Wooster, that twit about town; and his indefatigable manservant, Jeeves, who opened conversations by “a gentle cough that sounds like a very old sheep clearing its throat on a misty mountain top.” Along with Psmith (the “P” is silent, “as in the tomb”), he gave us characters who will live as long as the English language is in use.

He wrote his first golf stories during his lengthy American stay. There was a course near Great Neck on Long Island, called the Sound View Golf Club, where he played with famous American comic actors such as Ed Wynn and Ernest Truex. “The golf course was awfully nice,” he recalled late in life. “However, I wasn’t any good at golf. I suppose I ought to have taken lessons instead of playing. I didn’t mind losing, because it was such good exercise walking around the holes. If only I’d taken up golf immediately after I left school instead of playing cricket.”

Wodehouse never did get very good at golf. He won exactly one trophy, a striped umbrella, which he copped at a hotel tournament in Aiken, S.C., “where, hitting them squarely on the meat for once, I went through a field of some of the fattest retired businessmen in America like a devouring flame.”

By the 1920s, with his gemlike golf stories among a host of other work, the Wodehouse style had come to full flower and would stay in bloom for another 50 years.

A VERY LUCID BUZZ SAW

Now, if you will sit still for just a bit of literary criticism, I will reward you with a couple of nifty anecdotes.

The Wodehouse style is based on clarity and action. His writing is so lucid, you could make it out if it were written on the bottom of the Mindanao Deep. His plots rip along with the speed of a buzz saw working toward the heroine’s vitals. Wodehouse was a creature of the theater, and his stories are the book for small-scale musical comedies. If the story is as simple as Chester Meredith falling in love with Felicia Blakeney because she is the first woman he ever met who didn’t overswing, I would remind you that the plot of “Oklahoma!” is: Will Laurey go to the box supper with Curly?

Good writing has tension. You want to know how things come out. But there is little suspense in a Wodehouse golf story. You can see the socko finish a par 5 away. He created tension not by what he wrote, but by the way he wrote it. David Jasen, a perceptive biographer, points out Wodehouse worked in literary ragtime. Just as ragtime seems to be running all over the place but is actually well disciplined, Wodehouse wrote in syncopated sentences that seemed wild but were always under control. They are like little roller-coaster rides. You have the fun of being scared, knowing you are going to get to the end all right.

Here is the Master describing the much-married Vincent Jopp contemplating yet one more wedding before an important match:

There was nothing of the celibate about Vincent Jopp. He was one of those men who marry early and often. On three separate occasions … he had jumped off the dock, to scramble ashore again by means of the Divorce Court lifebelt. Scattered here and there about the country there were three ex-Mrs. Jopps, drawing their monthly envelope, and now, it seemed, he contemplated the addition of a fourth to the platoon.

It reads as The Forsyte Saga in four dazzling sentences.

Here are the anecdotes. It is axiomatic that humorists “see things funny.” It is less well known that funny things happen to funny people. Plum proposed to Ethel Rowley while having a violent sneezing fit. She accepted him anyway. That went into a story.

One time in New York, a beautiful woman appeared at his door. He thought she was an interior decorator come to look at a couch. She, however, was a model who had mistakenly come to his apartment thinking it was an artist’s studio where she was to pose. When Wodehouse showed her the couch, she took off her clothes.

That went into a musical-comedy sketch.

By 1927, he was rolling in royalty money. Ethel rented a 16-room London townhouse just off Park Lane with a household staff that included a morning and afternoon secretary as well as a cook, a butler, a kitchen maid, a footman, two housemaids, an odd-job man and a chauffeur. She fitted Plum up with a proper paneled library. He saw it was all lovely and then went to the kitchen and brought up a table to his bedroom, where he put his old Monarch typewriter and went back to work.

If Wodehouse was a literary lion, he was the most skitterish one in the pride. A desperately shy man, he once asked Ethel, during one of their many moves, to find a first-floor apartment, because he said, “I never know what to say to the lift boy.”

ARRESTED BY GERMANY, HURT BY ENGLAND

It is not given by the gods for man to live in perpetual sunlight. During World War II, Wodehouse did a very foolish thing. Living in France when the Germans swept into the country, he and Ethel tried to drive to the coast, but their vehicle broke down within two miles. Plum never did have any luck with cars. (He once owned a fancy Darracq. But he drove it into a hedge on his first outing. He got out, walked to the station, leaving his car behind, and never drove himself again.) He was interned by the Germans and spent the war in custody.

During his internment he agreed to do a few radio broadcasts, thinking they would reassure his friends he was all right. It was typically silly stuff, the sort of thing he might have written for Punch. In America, the broadcasts were considered models of anti-Nazi propaganda and might even have helped the Allied war effort. (The Germans, who took Wodehouse seriously, apishly copied his work and went so far as to parachute a secret agent into England dressed as a proper Wodehouse character. The poor spy was picked up almost immediately when it was noticed he was wearing a pair of lavender spats.)

That Wodehouse had broadcast for the Germans at all smacked of collaboration to some British authorities. Although he was cleared of all charges, the resulting furor hurt him deeply, and he never returned to England.

After the war he settled in Remsenberg on Long Island and became an American citizen at the age of 74 on Dec. 16, 1955. He said, “It’s like being asked to join a very good club.”

He settled back into the old happy grind. “Just writing one book after another,” he said. “That’s my life.” It never took much to start a new book. “I have a good plot,” he once wrote to a friend, “where he steals a chap’s trousers in order to go to a garden party and all that sort of thing.”

He wrote his last golf short story, “Sleepy Time,” in 1965, at the age of 84. It was as spritely as his first, written 55 year before. Under hypnosis, Cyril Grooly, a 24-handicapper, makes a 50-foot putt for a 62 to beat the fearful Sidney McMurdo, who is reduced to making “a bronchial sound such as might have been produced by an elephant taking its foot out of a swamp in a teak forest.” Cyril almost marries Agnes Flack in the bargain, but the always benign P.G. Wodehouse would never let that happen.

It was a quiet schedule, but with the encroachments of age, he was down to writing only about four pages a day. The rest of the time, he and Ethel walked their dogs, watched soap operas on television and shared iced martinis in the evenings. They sometimes enjoyed a spot of bridge. Bridge was another game he was not particularly good at. Once when asked why he hadn’t played his ace of spades earlier, he replied tartly, “I played it the second I found it.”

The artifacts of fame, which he did not require, came to him anyway. He tried to avoid interviews if he could do so without giving offense, but he did agree to sit as a model for Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum. The figure came out looking more like Dwight Eisenhower. In December 1974, he was created a Knight Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II. Two months later, he slipped out of the world with even less fuss than he had come into it. At the age of 93, he checked into a Long Island hospital suffering from a disorder afflicting his circulatory system called “pemphigus,” a Wodehousean malady if there ever was such a thing. On Feb. 14, 1975, as he was walking in his room, he died in a moment. At the time, P.G. Wodehouse was revising the typescript of his 96th novel.

Wodehouse is not well regarded by academicians. My copy of the Oxford Companion to English Literature grants him a scant 10 lines, a fraction of the space given over to Anthony Wood, a 17th-century antiquarian whose major work, Athenae Oxonienses, caused something of a stir when it was published in 1691. Wodehouse’s very lucidity inveighs against academic evaluation. You might as well teach a college course in advanced Henny Youngman.

But Wodehouse is read now by the millions, as he always has been. When Herbert Asquith went down to defeat as Prime Minister in 1916, he consoled himself with Wodehouse, and when the great Catholic prelate, Msgr. Ronald Knox, lay dying in 1957, he called for books by Wodehouse.

P.G. Wodehouse got his share of bad reviews, and he hated them. “I feel as if someone had flung an egg at me from a bomb-proof shelter,” he said after one vigorous panning. William Lyon Phelps, a distinguished critic, was closer to the mark when he wrote of Wodehouse, “With him humor is not a means but an end. His intention is pure diversion; he wishes to make us laugh. … That is, outside of supreme creative genius, perhaps the most difficult thing to accomplish in literary composition. Many try, but few succeed.”

On Wodehouse’s 80th birthday, with a dozen novels still left in him, he accepted the congratulations of the civilised world and, in the way of a meticulous craftsman, he provided his own best review and epitaph:

“When in due course Charon ferries me across the Styx and everyone is telling everyone else what a rotten writer I was, I hope at least one voice will be heard piping up: But he did take trouble.”