*Actually, we asked some of the leading architects in golf how they would change the home of the Masters if they had the opportunity. Their answers, in sketches and words, ranged from tweaks to overhauls

By Ron Whitten

How can Augusta National be improved?

That may seem like a frivolous question, given that the course, the perennial home of the Masters, is currently No. 2 on Golf Digest’s 2019-2020 ranking of America’s 100 Greatest Golf Courses, and was previously ranked No. 1 in six out of the past 11 years.

But it’s a legitimate question, mainly because club officials are quietly thinking about it all the time. Just this past summer, a new back tee was installed on the par-4 fifth, lengthening the hole by 40 yards, to 495 yards, uphill, and its fairway bunkers were repositioned and rebuilt to provide even more challenge for Masters competitors.

Among championship courses, Augusta National has been modified more than most, dating back to the late 1930s when the seventh and 10th greens were relocated. So change is not a taboo topic.

How can Augusta National be improved? That’s the question I posed to a dozen prominent golf course architects back in 1998 and not one of them would go on record with a suggestion. Faced with such a dry hole, this writer resorted to proposing his own changes to Augusta’s closing four holes in a piece entitled, “Masters Makeover” in that year’s April issue.

But there’s a different generation involved in design these days, so I recently tossed out that same softball (or hot potato, depending upon your viewpoint) to 20 active golf architects across the United States, and this time, while half responded with regrets, the other half offered thoughtful concrete ideas.

There were a couple of common themes. Most feel that holes should be widened out, by eliminating the rough (what Augusta National officials call “the second cut”) or by eliminating some of the pine trees planted in the last two decades. “Tree planting has nullified some of the strategic opportunities that this incredible course used to offer,” says one architect, John Fought.

“The club has instituted rigid tree planting,” says another, Brian Silva. “Everything is planted in rows. It looks artificial.”

Several also feel that the bunkers could be reshaped to add a bit more movement and flair, in keeping with those of original architect Alister MacKenzie. (The only MacKenzie bunker still in existence at Augusta National is the one in the fairway on the par-4 10th, a gorgeous creation not really in play for Masters competitors.)

But when it comes to specifics, each of the 10 designers has their own take. Which is not surprising, given that there are no right or wrong answers in golf course architecture.

Three on 3

This difference of opinions is graphically demonstrated with the third hole, where three architects proposed three separate and distinct changes to that short, testy par 4.

Fought, now 65 years old, played in the 1977 Masters as an amateur, back when the hole featured just a single fairway bunker and a single greenside bunker, both on the left.

Architect John Fought would re-establish an alternate fairway to the left.

“The third green has always had a right-to-left slant to it,” Fought says, “and veteran Masters players told me it was impossible to hold it on the green when approaching it from the right side. So I aimed way left off the tee, over by that bunker, which gave me a perfect angle for the second shot into the slope of the green. Everything was tightly mowed back then, remember. I called it the alternate fairway.”

In the summer of 1982, Bob Cupp of Jack Nicklaus’s design firm remodelled the hole, replacing the sole fairway bunker with four smaller ones scattered about, around newly created knobs. (Little known fact: Cupp and Nicklaus had originally discussed building a pond in that locale, at the request of then-Masters Chairman Hord Hardin, but the drainage wouldn’t work.)

“I qualified for the 1984 Masters [as a tour pro],” Fought recalls, “and when I got there, I found I couldn’t approach the third hole from the same spot on the left as I had in 1977 and 1980. They’d filled that area with bunkers.

“But there was still tightly mown turf around those bunkers, so I tried to land my tee shots behind the cluster of bunkers to get that good angle into the green.”

But in 1999, Augusta National started growing rough, which eliminated Fought’s alternate fairway on No. 3 entirely. These days, no one tries to play it the way Fought thought ideal.

His proposal is to return the alternate fairway behind the fairway bunkers by mowing the adjacent area at fairway height. Ironically, the club has always had a small jug-handle of fairway that connects the third hole to the seventh. Fought’s proposal is to simply widen that swath closer to the bunkers, providing ample room to land a tee shot with something less than a driver. that would result in a longer approach into the third green than if hitting directly down the fairway but would provide a far better angle into the green.

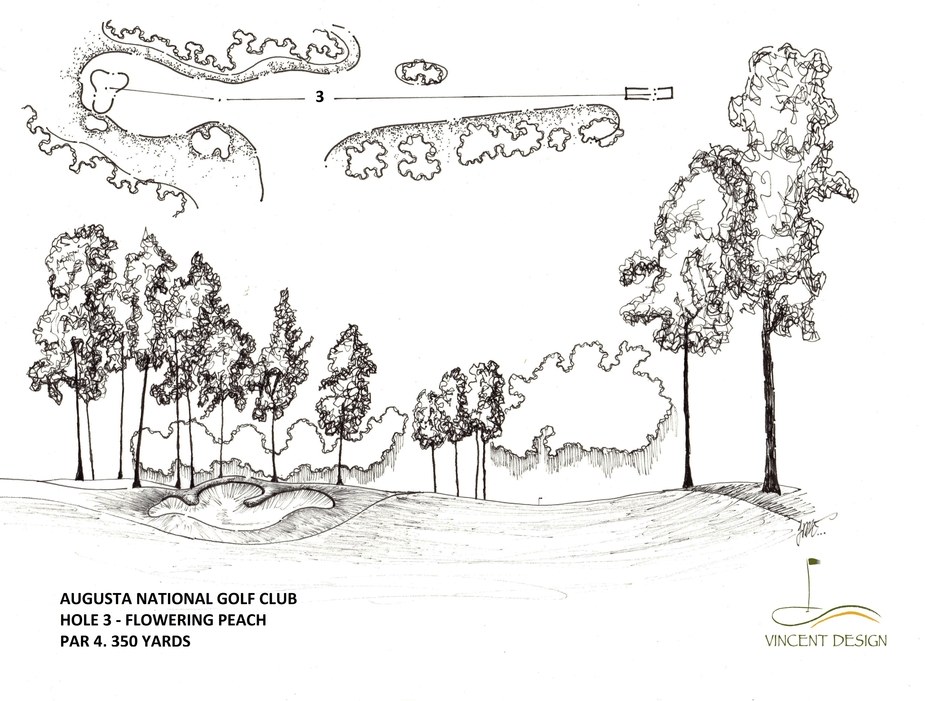

Idea No. 2: Troy Vincent, a 52-year-old former associate of Jack Nicklaus who now runs his own design firm in his hometown of Augusta, has spectated at the Masters for over 30 years and has witnessed first-hand some of the evolution of the course.

“The fairway bunkers on hole 3 have always been an issue for me personally,” Vincent says. “It’s the only hole on the course with four fairway bunkers. The front two bunkers are not only similar in size but sit parallel to each other. The other two bunkers are again, comparable in size and orientation.

“The original design had one large fairway bunker that in essence pinched off the fairway. That created a sort of ‘speed slot’ to the right, although the advantage of hitting that speed slot was debatable, due to the orientation of the green.”

Troy Vincent would replace the four fairway bunkers with a single prominent one.

Vincent proposes removing the four bunkers on hole 3. “Let’s create a single fairway bunker that fits both strategy and style that is apparent on the other six holes at Augusta National that feature fairway bunkers. This revised bunker would begin just beyond where the current first two bunkers are located to allow the average player a little more room off the tee.”

Vincent would sculpt the bunker-like others on the course, “…with high flashed sand, fingers and noses that torque and twist. The golfer that hits into the far end of this bunker would have a difficult shot to the green.”

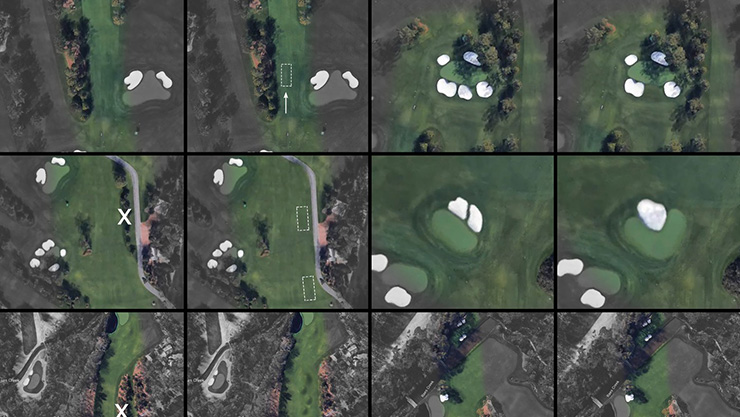

David McLay Kidd’s revised third hole, with tees, pushed forward, as it would appear in satellite images.

Idea No. 3: David McLay Kidd, the 51-year-old Scot who designed the first course at Bandon Dunes and one of the hottest designers presently in the business, envisions a third hole that is shorter, with more risk and reward.

Kidd feels the third should become a risk-reward drivable par 4.

“The third hole is the shortest [par 4] on the course, at 370 yards,” he writes. “In my opinion, it lacks drama, it does not encourage the field to take risk.”

Kidd would move the championship tee forward 50 yards, turning the third into a 320-yard, reachable par 4, a hole where many wouldn’t even need driver off the tee to still gamble to reach the green. He’d also reposition and add bunkers.

“If the fairway snaked its way through a minefield of bunkers and slopes that offered safe harbour in select spots [and] a gradually improving opportunity for the second shot, just how would the world’s best play it?” he writes.

Augusta National has long had a tradition of par-5 holes where bombers can attempt a risk that could result in an eagle, but it has curiously never considered a reachable par 4, a very popular feature on many of today’s championship courses. Indeed, back in 1937, after Byron Nelson drove the seventh green, the club soon commissioned the relocation of that green to prevent a repeat.

Kidd agrees that a drivable par 4 is “a very difficult hole to get right from an architect’s perspective,” but when it’s done right—think of the 10th at Riviera and the 17th at TPC Scottsdale—it can enhance the excitement of an event. Coupled with the potential of an eagle on the preceding hole (the downhill par-5 second), the chance of another eagle on a reachable par-4 third could indeed leapfrog a Masters competitor to the head of the field. The Masters could well begin on the front nine on Sunday instead of the back nine.

Taking something from 7

Bill Bergin, now 60 years old, played professional golf for six years in the early 1980s, and competed in five majors, although he never qualified for the Masters. Now based in Atlanta, he has run his own golf design firm since 1994, after learning the business from Bob Cupp. In his study of Augusta National, the one hole Bergin finds less than perfect is the seventh.

After Perry Maxwell built the present green atop a ridge in 1938, the seventh hole became a drive-and-precise-pitch hole, playing down a narrow tree-lined fairway to a wide, shallow, elevated green protected by three bunkers across the front. The strategy has always been to keep it between the trees off the tee and aim for the back of the green to ensure clearing the bunkers. The championship tee was moved back in 2002 from 365 yards to 410 yards, and in 2006 to 450 yards. Suddenly, some competitors found themselves playing 5-irons into a green designed for a 9-iron shot.

Bergin thinks one simple change could enhance this hole’s dynamics.

“To counteract the disconnect between the design of the green complex and the length of the approach, the central front bunker could be eliminated and replaced with a relatively steep, closely mown grass slope,” he says. “This minor adjustment will have a big impact. An unguarded hole location may be more inviting; however, a ball that comes up just short will roll well back down into the fairway, and players will be wishing they were in a bunker.

“Players hitting shots from the trees left or right will have a chance for heroic recoveries, which are always exciting for patrons gathered around the green. And members and their guests will find the hole simply has more options, for they can run the ball up and onto the green if they choose. This minor adjustment will be more intriguing for Masters contestants and more fun for the membership.”

Bill Bergin feels the removal of a single bunker in front of the seventh green changes its dynamics.

In support of Bergin’s proposal are the words of course co-designer Bobby Jones, who in 1951 wrote of the present seventh green, “It is particularly difficult to stop a ball on the green with the following wind.” Given that, it’s logical to assume that Jones would have favoured creating a small avenue onto the putting surface by the removal of that one bunker.

The ever-changing 8th

Bruce Charlton’s vision for the par-5 8th hole.

Augusta National’s uphill par-5 eighth is one of the holes that has changed the most. Its punchbowl green was bulldozed away in the mid-1950s, relocated and replaced not just once but twice before a replica of MacKenzie’s green and surrounding high knobs of short grass was created in its original spot in 1979.

In the beginning, the eighth had one pretty bunker smack in the middle of the fairway, which meant players had to play left or right of it or carry it. In 1957, George Cobb relocated the bunker to the right edge of the fairway. Over the years, new back tees have been added, eventually stretching the once 500-yard hole to its present 570 yards. Each time a new back tee was added, it was located to the right of the former one, reflecting an extended effort to force a fade off the eighth tee.

Architect Bruce Charlton would move the back tee on eight once again, but he wouldn’t lengthen the hole. “It needs to remain a birdie hole, with possible eagles for big hitters,” says the 61-year-old Californian, who was co-designer of Chambers Bay, the 2015 U.S. Open site.

Charlton would simply shift the championship tee to the right some 20 yards or so, whatever it takes to make that fairway bunker a “carry bunker” off the tee. (A row of pines would likely have to be removed to provide airspace for the drives from the new tee. An existing road should also be relocated for aesthetics.)

From the present tee, it takes 295 yards to clear the far edge of the bunker, but few competitors see the need to bring it into play, there being ample fairway to its left. Charlton’s new tee would bring that bunker front and centre off the tee, much in the way it was in the beginning.

He’d shift the tee forward, too. “A tee forward and to the right could also benefit the members,” Charlton says, for it would give average golfers, who tend to slice the ball, far more fairway on the left to aim at.

Reinstitute a ‘MacKenzie favourite’ at the 9th green

Tom Doak’s ninth hole revision, as it would appear in satellite images.

Tom Doak is known for creating world-ranked courses like Pacific Dunes in Oregon and Tara Iti in New Zealand. But when the now 58-year-old Doak burst upon the scene in the mid-1980s, what first grabbed our attention was his writing in architecture. He was perhaps the sharpest critic of his time, willing to call out shortcomings infamous courses when few would.

Back in 1987, Doak wrote of Augusta National: “So many revisions that MacKenzie might not recognize it today.” He lamented “how completely it’s changed from his vision.”

Back then, one of the Augusta National holes Doak said he could “do without” was the par-4 ninth. He’s still not a fan of it today.

“The present ninth green is not a great green,” Doak says. “It’s super severe with only one way to play it: get it up the hill but keep it below the hole. It’s one of the most difficult holes for member play. If you don’t get up the hill with your second shot, it might roll back 75 yards. And if you go long to be safe, your putt might wind up all the way back down the hill.

“As a big believer in restoring cool features that have been lost, I would recommend the club restore the original boomerang green at the ninth. The original green, shaped much like the seventh green at Crystal Downs or the 14th at the University of Michigan course [both Alister MacKenzie designs as well], had two distinct sections that offered a more receptive approach, although the left one was wrapped around a bunker that you might have to carry to get to it.

“If you reintroduced the old green, the pros would face a different approach shot depending upon where the pin is. When the hole is on the left wing, you could hit to the back of the green and let the contours feed the ball down to the left. Which is a much different shot than they face today.”

Bring back Alister MacKenzie’s boomerang green on the par-4 ninth, says Tom Doak. (Graphics courtesy of Doak associate Ryan Farrow)

Doak sees little chance that his suggestion will ever be implemented.

“To the club’s credit,” he says, “they know what their mission is. It’s the Masters, not the preservation of MacKenzie architecture. I think the ninth green is one of the few items of restoration to the course that would reinstitute MacKenzie and yet still challenge today’s tour pros. But they’ll never pursue that idea because the club started prioritizing challenge for professionals above fun for members quite a few years ago. That’s too bad because I do believe Bobby Jones intended to strike a balance of both.”

Trees and mounds on 11

Architect John LaFoy wants to reclaim the best angle into the 11th green by removing trees on the right.

Idea No.1: At 73, John LaFoy of Greenville, S.C. is the oldest golf architect in this exercise and the only one who has actually worked on remodelling Augusta National. Forty years ago, after a stint in Vietnam, LaFoy worked alongside his mentor, architect George Cobb, on several projects at the behest of then-Masters chairman Clifford Roberts.

“Over a period of five years,” LaFoy says, “we moved back a lot of tees. Moved back the 13th tee as far as we could go at that time. And the second tee, and the sixth tee. We redid the 13th green, reestablishing a prominent contour on the back right that had become diminished through topdressing. We also sharpened the slope on the 18th green.”

If LaFoy were working there today, he’d address the 11th hole.

“There are simply too many trees on 11,” LaFoy says.

That’s because, in 2003, the club transplanted 36 mature pine trees down the right side of the landing area on the 11th hole, a move that then-Masters chairman Hootie Johnson said, “continues our long-standing emphasis on accuracy off the tee.” The club transplanted more trees along the 11th in 2005 and, although a few were removed in 2007 “to enhance patron view,” the net effect has been a far more narrow fairway than existed 20 years ago.

“I measured it,” LaFoy says. “In 2000, from tree-line to tree-line, the 11th hole measured 280 feet. Now, tree-line to tree-line, it’s 160 feet. the corridor has shrunk. the fairway itself had been 115 feet wide at 290 yards off the tee. Now it’s only 100 feet wide.”

Before the tree-planting, competitors would aim for the far right side of the fairway off the tee so they’d have a straight-in downhill second shot to the 11th green. Drives to the centre or left portion of the fairway resulted in approach shots that had to carry the corner of the pond at the front left of the green.

“The tree planting took away the best angle into the green, from the far right side,” LaFoy says. “Now there’s only one way to play the hole. Everybody has to flirt with that pond.”

LaFoy’s solution would be to transplant those pine trees once again.

“If you look at it from the air, it’s a long, skinny peninsula of trees with the fairway on the left and a grassy strip to the right. I’d get rid of those trees, transplant them over onto that strip of grass to the right, and widen the fairway to incorporate most of the area where we took the trees out. I’d put knobs and moguls in where the trees had been, and maintain most of the area as fairway cut. But I’d have some second cut on some knobs, too.

“I’d put those mounds or moguls in at random, nothing with any pattern to it. I’d just want some rolls and humps that could pose awkward lies. This area should once again become the best angle into the green, but it could become a harder shot than from the centre of the fairway if you end up with a bad stance on a mogul.”

Idea No.2: At 36, Kyle Franz of Southern Pines, N.C. is the youngest architect offering a change to Augusta National. He, too, would address the 11th hole, but would focus not on the tee shot, but on the approach.

Franz would reinstate the “kicker mounds” that stood right in front of the 11th green. They were part of the original MacKenzie/Jones design, inspired by features of the Old Course at St. Andrews.

Kyle Franz points out the present mounds short of the 11th green aren’t what MacKenzie intended.

They were designed, Franz says, “to bounce approach shots onto the putting surface, avoiding the famous water on the left. The player that aimed safely right, with a running draw, could bounce down the hillside onto the green. This would avoid all trouble. Conversely, the mounds would also kick weak shots capriciously away from back-right pins. It’s a textbook example of a single design feature, intended to both help and hurt players, depending on the hole location.”

Those mounds, now reduced in size, are still evident on the hillside above the 11th green, but they are well short of the putting surface and are ineffectual. “A few years ago, a Masters contestant tried using them to kick onto the green,” Franz says. “Instead, his shot bounced wildly left and into the water. One out of 300 players attempted it, and it ended in disaster. MacKenzie would cringe.”

Franz would rebuild the mounds closer to the green. “Almost all the way to the green,” he says. In old photos, “…it looks like a spine meanders off the mounds all the way to the edge of the green, probably even into it. That is what I would expect of MacKenzie, extending external contours into the green to continue propelling balls.

“I’d keep the shapes simple and gentle. Make the mounds maybe two feet higher than they are now. It looks like the mounds were high enough to obscure the view from certain sections of the fairway.”

Their shape, Franz emphasizes, should not induce any sharp left bounce that would careen a golf ball into the water.

The untouched 12th

Brian Silva says it’s time to add new back tees on 12 to again make it play as a 7-iron shot.

New England architect Brian Silva, at 66 now a part-time resident of Florida, has long been a critic of the USGA’s failure to limit the advances of technology, particularly in the total distance of a golf ball. Yet when asked about what improvement he’d contemplate at Augusta National, his response was surprising.

“I’d continue to look for length, for places to push back tees,” Silva says. “I don’t know why people are offended by the idea of trying to lengthen the course so that we can force players to hit what clubs Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer used to hit in their prime. Why reject the idea of adding length to try and make the holes play as they did 50 years ago?”

Of course, most of the holes at Augusta National have been lengthened over the years, many of them several times. The one hole that has remained nearly untouched from the beginning is the par-3 12th, the famed shot through swirling winds over Rae’s Creek to a wide, shallow green. It was 150 yards when the club opened in late 1933. It measures 155 yards today.

“There’s plenty of room to move the tee back on 12,” Silva says. “What is there? An empty slope, filled with bleachers and a Pimento cheese sandwich shop during the Masters. You could very easily move those things around a bit and build a new tee back there.

“Get the hole to play more like originally intended. Growing up watching the event, I remember it was predominantly 7-iron shots into 12 green. Today, the club of choice is a 9-iron or wedge.

“So move the tee back to whatever length forces them to play a 7-iron. How long does Rory McIlroy hit a 7-iron? Or Patrick Reed? Or Tiger Woods? I just want them to experience the same thrills that Jack and Arnie experienced.”

While yardage figures vary, depending upon the player and source, Trackman statistics based on PGA Tour play show an average carry for a tour pro’s 7-iron to be 172 yards. Thus, a new tee box in the range of 165 to 185 yards would only require some 30 yards of space behind the present 12th tee complex.

“I know some will consider this blasphemous,” Silva says. “You can’t be changing the Good Doctor MacKenzie’s work. But clearly, his work has already been changed by the game. I’m for getting holes playing more along the lines that Alister intended. Why not restoring Alister’s intent by adding length to the 12th hole, so that 7-irons were again the club of choice?”

Penultimate thrills

Art Schaupeter loves the Masters and its course so much that he incorporated a few Augusta National-inspired elements into his latest design, the new TPC Colorado north of Denver. He especially admires the excitement created by Augusta’s 13th through 16th holes.

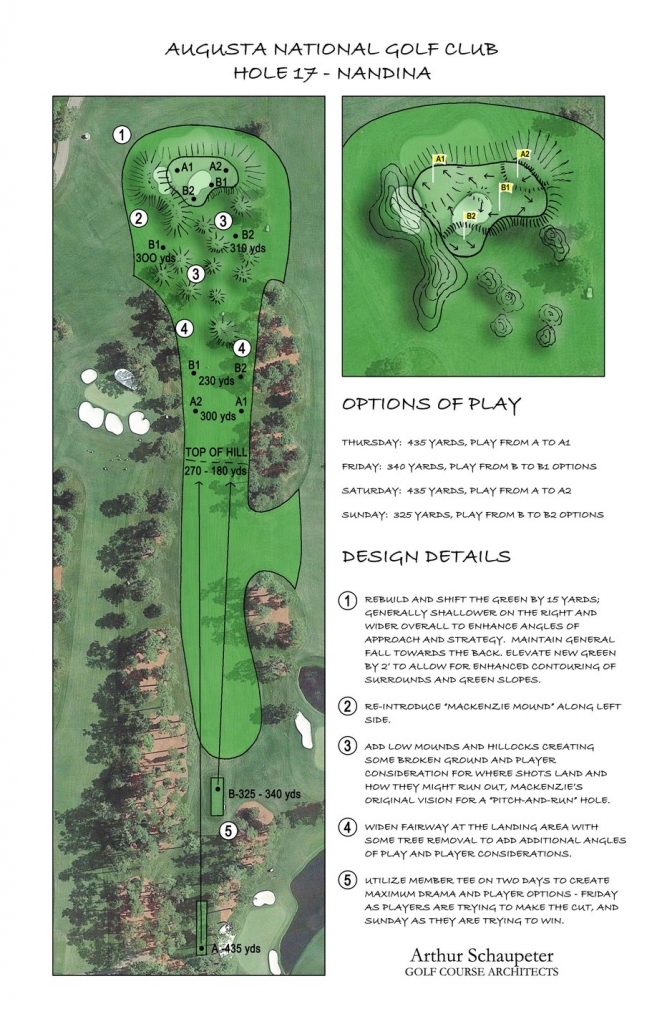

“Hole 17 has always felt a little lost in terms of excitement and anticipation,” the 53-year-old Schaupeter says. To provide more fireworks, he proposes restoring some MacKenzie principles that have been removed from that hole over the years.

Originally, the 17th green was another inspired by the Old Course at St. Andrews, bunkerless and contoured to encourage a low, run-up approach. Some prominent mounds, much like those on 11, framed the approach. In the late 1930s, Perry Maxwell redesigned the green and added frontal bunkers, deviating from MacKenzie’s intended pitch-and-run approach, and the mounds were eventually removed.

Schaupeter would redesign and reposition the green, making it slope slightly away from players. He’d fill in the bunkers and re-establish hillocks and undulating ground both in the approach area and back down the fairway.

Art Schaupeter would replace the greenside bunkers at 17 with mounds and hillocks.

He’d also remove trees to widen the fairway for more angles of possible approach to different hole locations.

He also proposes playing off the members’ tees on certain days of the Masters to provide a short, uphill-but-reachable par 4 that could provide a possible two-or-three shot swing late in the round.

“Extend the drama, excitement and potential for more “Augusta roars” ringing through the pines with a risk-reward hole,” Schaupeter says. As he points out, we have to go back to Jack Nicklaus’ last Masters victory in 1986 to think of a genuine thrill occurring on the 17th hole.

Bonus: Lucky No. 13

Juiced by the stimulating suggestions of these designers, I can’t resist offering a proposal of my own in conclusion. With my ample belly of course design experience, I feel qualified to do so. Besides, I’ve done so before.

My change would be to the par-5 13th. In 2017, Augusta National purchased a piece of property from the adjacent Augusta Country Club, mainly its ninth hole. Last summer, Silva constructed a new eighth green and a new ninth hole for Augusta C.C. on different land, and those holes opened for play last fall. That event now allows Augusta National to push back its championship tee on the par-5 13th by as much as 50 yards, and I suspect that could occur in the summer of 2019.

While that should keep golfers like Bubba Watson from driving over the pine trees on the left to within a sand-wedge second shot distance of the 13th green, the fact remains that the turning point for most drives from such a new back tee will still be within a 6-iron second shot of the green for many Masters competitors.

To truly return the gamble on the 13th to what Bobby Jones envisioned as a monumental decision to challenge the creek in front of the green, the second shot must be lengthened as well. There is ample flat land in the dense pine trees behind the present 13th green to push the green back at least 50 yards. Given today’s laser technology, the serpentine creek, putting surface and bunkers could all be precisely reproduced, although I’ve never been keen on that waist-deep swale between the bunkers and green installed by Jack Nicklaus in 1983.

Re-creating the stream and green 50 yards deeper from their present location, coupled with a new tee 50 yards back, would transform the present 510-yard par-5 13th into a 610-yard par 5 without losing any of its sensational playing characteristics. It would play as a drive-and-a-possible-fairway-wood to hit the green in two. To keep it within range of average golfers, I’d also create a new forward tee, over near the drop area for the par-3 12th.

Leave it to me to propose the most radical, and costly, change to Augusta National. But if my idea seems implausible, that may just be because the other suggestions are so reasonable, so easily achievable, some with simply an adjustment in mowing height or a few pallets of sod, others with just a tree spade or back hoe.

Although it would cost a pretty penny, this writer thinks the 13th green complex can be duplicated 50 yards back in the woods.

The lesson of this exercise is one every golfer can carry to their home course. It never hurts to have a set of professional eyes periodically review your course’s design. The game of golf is never static; the playing fields of the game can’t remain static either.

THE PARTICIPATING GOLF ARCHITECTS (LISTED ALPHABETICALLY):

Bill Bergin, member American Society of Golf Course Architects. Bergin Golf Designs, Atlanta. Notable designs include Foxland at Tennessee Grasslands, the remodeled Chattanooga G. & C.C. and Country Club of Winter Haven in Florida, with Rees Jones as a consultant. Recently completed the redesign of Chickasaw C.C. in Memphis.

Bruce Charlton, ASGCA. Robert Trent Jones II, Palo Alto, Calif. Notable designs include Chambers Bay in Washington, Blessings in Arkansas and the Patriot in Oklahoma (all co-designs with partner Robert Trent Jones Jr.). Currently working on Zala Springs in Hungary.

Tom Doak, Renaissance Golf Design, Traverse City, Mich. Notable designs include Pacific Dunes in Oregon, Streamsong Blue in Florida and The Loop in Michigan. Currently remodeling Memorial Park in Houston as the new venue for the PGA Tour.

John Fought, ASGCA. John Fought Design, Scottsdale, Ariz. Notable designs include Sand Hollow in Utah, Windsong Farm in Minnesota and the Galley near Tucson. Currently renovating Alpine C.C. in Utah.

Kyle Franz, KMF Golf Course Design, Southern Pines, N.C. Notable designs include restorations of Mid-Pines and Pine Needles, both in Southern Pines, and Country Club of Charleston, S.C., site of the 2019 U.S. Women’s Open. Currently restoring Minikahda in Minnesota.

David McLay Kidd, DMK Golf Design, Bend, Ore. Notable designs include Bandon Dunes in Oregon, Gamble Sands in Washington and Mammoth Dunes in Wisconsin. Currently, Kidd is touching up Bandon Dunes in preparation for the 2020 U.S. Amateur.

John LaFoy, ASGCA. John LaFoy Golf Course Design, Greenville, S.C. Notable designs include Glenmore and Kiskiack, both in Virginia and Quarry Oaks in Nebraska. Currently completing the remodeling of the East Course at Country Club of Birmingham, Ala.

Art Schaupeter, ASGCA. Arthur Schaupeter Golf Course Architects, St. Louis, Mo. Notable designs include the Club at Old Hawthorn in Missouri, the Highlands of Elgin in Illinois and TPC Colorado. Will soon begin construction of the Valor Club, San Antonio on the site of the old Pecan Valley Golf Club.

Brian Silva, Brian M. Silva Golf Design, Dover, N.H. Best known for Black Rock Club, Cape Cod National and Great Horse, all in Massachusetts. Recently completed restoration of Biltmore GC, Coral Gables, Florida.

Troy Vincent, ASGCA. Vincent Design Golf Course Architecture, Augusta, Ga. Best known for Santa Maria G & C.C. and Buenaventura G.C., both in Panama, and Timber Banks in New York, all Nicklaus Design projects. Currently remodeling Augusta (Ga.) Municipal Golf Course.