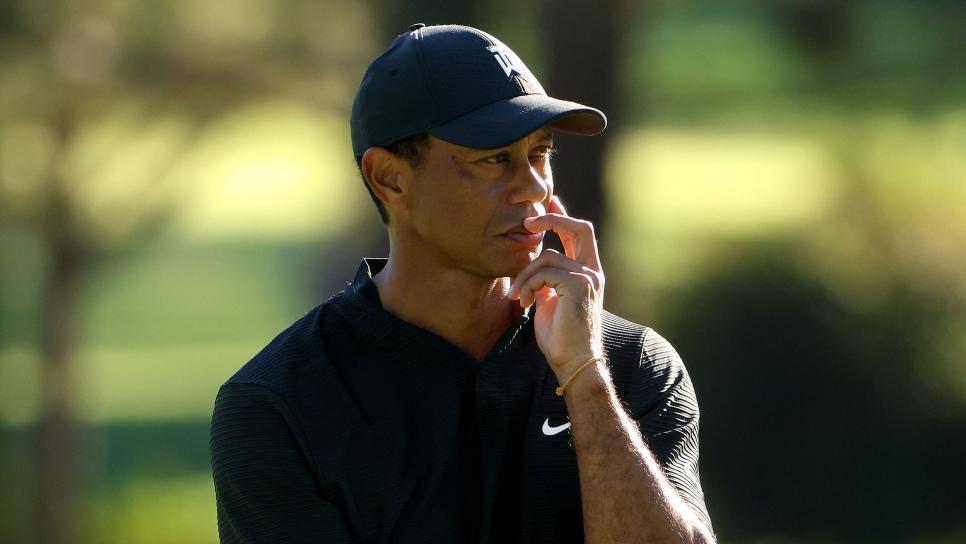

Jamie Squire

By Daniel Rapaport

If you’re completely surprised, you haven’t been paying attention.

Disappointed, that’s one thing. But the news that Tiger Woods will miss at least a few months after a microdiscectomy procedure to his back is a shock only to two groups of people: Those who never fully appreciated the remarkable scope of his comeback in the first place, and those who have not listened to the man speak over the past three years.

It bears repeating that Woods’ spinal fusion in April 2017 was a true last-gasp attempt to save a career on life support. A medical Hail Mary, so to speak. He’d been battling back problems for a half-decade, and the first three microdiscectomies he had beginning in 2015—all similar to the one he’s recovering from now—provided only some relief, none of which was particularly long-lasting. The prospect of a fusion loomed ominously in the background, something to turn to when all else failed. And by April 2017, with Woods having played three competitive rounds in the previous 20 months, all else had failed. There was nowhere else to turn but the fusion.

“Imagine the discs in the back as a stack of jelly donuts,” says Dr. Ara Suppiah, a functional sports medicine expert and a Golf Digest contributor. “Sometimes, the jelly from one doughnut leaks, and what the microdiscectomy does is takes off a piece of the doughnut. Now, when the whole system becomes unstable, that’s when they fuse the spine.”

The list of players to make a full recovery from a spinal fusion—which, by Woods’ standards, would mean returning to his healthy form—was virtually non-existent. So uncertain was Woods about whether he would ever play again that five months after the procedure, at the Presidents Cup at Liberty National, he painted an ominous picture: “I don’t know what my future holds for me.” More foreboding than his actual words was his tone: resigned, accepting. Even the fiercest competitor this sport has ever seen realized full well this was an opponent he’d never vanquish.

You know what comes next. Signs of life at the Hero World Challenge, three months later. Contending at a PGA Tour event three months after that. Winning the Tour Championship in September 2018, the Masters the following April, then tying Sam Snead with his 82nd PGA Tour win in October 2019.

And yet, throughout his remarkable play for that two-year stretch, Woods always made clear that he was competing on borrowed time—that this is all gravy. In public, and in private. As someone who attended each of Woods’ events the past 15 months, I can say with certainty that he never deluded himself into believing he’d been cured. He tightens up after virtually every single round. Even the really good ones. It usually starts during the post-round media interviews, but sometimes it starts earlier. There are days he wakes up stiff as a flagpole, unable to turn and un-abler to bend down.

He had one of those on Friday of last year’s Memorial, when he needed to use his wedge as a cane to get out of a bunker and the rest of us cringed. “Aging is not fun,” Woods said that day. “Now I’m just trying to hold on.” It happened again on Saturday of the November Masters, when he offered a particularly depressing assessment of his reality: “I can walk all day. The hard part is bending and twisting. I think that’s part of the game, though, and so that’s always been the challenge with my back issues and I guess will always continue to be.”

There is, of course, a medical explanation for what he’s been feeling.

“It’s like a really bad toothache—you have the sharp pain, and then you can feel a nagging severe ache in the whole region,” Suppiah says. “So it’s not just the lower back. You can get pain down the leg, the glutes, the front of the thigh, depending on which nerve is being affected.

“[The cause is] all the power and speed he creates in his swing. Each time he does that, he runs the risk of unsettling everything again. He tested the spine repeatedly after doing a full rehab post-fusion, and this occurred again, so it can be ominous.”

Icon Sportswire

Tiger Woods stretches his back during the second round of the 2020 Genesis Invitational.

Reading between the lines: This latest microdiscectomy should buy him some time. He’ll likely feel—and hopefully, play—better when he returns, whenever that may be. But the fusion wasn’t a cure, and neither is this. Woods’ back struggles are not going anywhere. It’s golf’s inconvenient truth. And Tuesday’s news was an unwelcome reminder of that truth. It’s also a reminder of just how unlikely his return to the mountaintop has been.

This is not to count Tiger Woods out. Surely, by now we know better than to do that. He could win 10 more tournaments and he could win zero, and neither would be particularly surprising. But “could” is quite different from “should.” As far as Tiger Woods’ golf goes, the only guarantee is unwavering effort. He’s going to work his butt off to get back into playing shape, and he’ll grind like he always does once he does return. He will keep pushing that rock up the mountain, no matter how many times his body fails and forces him to start from the bottom.

Woods’ body has changed. Twenty-five years as a professional, five back surgeries and five knee surgeries will do that. And, as a result, so too have his expectations and relationship with golf. The one constant, through everything, has been the drive to compete. The first four back surgeries didn’t crush him, and there’s no reason to believe the fifth—or a sixth or a seventh—will strike the decisive blow. Because while Woods knows what he’s up against, he’s never been the type to shy away from a battle.