How Tiger’s 12-stroke win 20 years ago changed the Masters and golf

by Tom Callahan

verybody remembers how it ended, but nobody can say exactly when it began.

verybody remembers how it ended, but nobody can say exactly when it began.

Some start the clock the week before the 1997 Masters, when, playing a practice round with Mark O’Meara, Tiger Woods shot 59 at Isleworth while neglecting to birdie two of the par 5s. On the plane ride to Augusta from Orlando, the friends got to talking:

“Do you think it’s possible to win the Grand Slam?” 21-year-old Woods asked 40-year-old O’Meara, then 0 for 54 in major championships. Mark looked at Tiger and thought, You’re the first guy since Nicklaus even

to ask the question, but didn’t say that out loud.

“Unrealistic,” O’Meara replied after a long moment.

“I think it’s possible,” Woods said.

The tournament itself—72 holes as impactful as any ever played—commenced April 10 and climaxed April 13, 20 years ago, kicking off on a blowy Thursday when flying pine needles punctured the air and the first 30 players were immediately whooshed over par. Three victories into his pro career, but still the holder of the U.S. Amateur title, Woods was paired, per tradition, with the defending champion, Nick Faldo. Tiger went out in 40. So, the story might open with his comeback, the birdie at 10, or perhaps with something that happened the day before, Seve Ballesteros’ 40th birthday, when Woods played half a practice round alongside Ballesteros and Jose Maria Olazabal. Breaking off from the Spaniards to try “a few little things” Seve had showed him, Tiger said that evening, “He’s amazing around the greens. There are some things you can learn only from another player.”

On the property but not in the gallery, preferring to watch on television, Earl Woods saw Tiger chip in at 12 to revive his first round. Being more sentimental than his son, Earl wondered if that wasn’t one of those little strokes of genius courtesy of Seve. “C’mon, Pop,” Tiger chided him later, “don’t get carried away.”

Recuperating from open-heart surgery, Earl was napping on the couch at the house they were renting in Augusta, and Tiger was reluctant to stir him. “Daddy,” he whispered finally, which startled Earl. Tiger almost never called him that anymore. “How do you like my stroke?”

“I don’t,” Earl replied in that deadpan, singsong voice that sometimes made Tiger laugh, but not this time.

“What’s wrong with it?”

“Your right hand is breaking down just slightly on the takeaway.”

Earl went to bed and Tiger continued putting on the carpet.

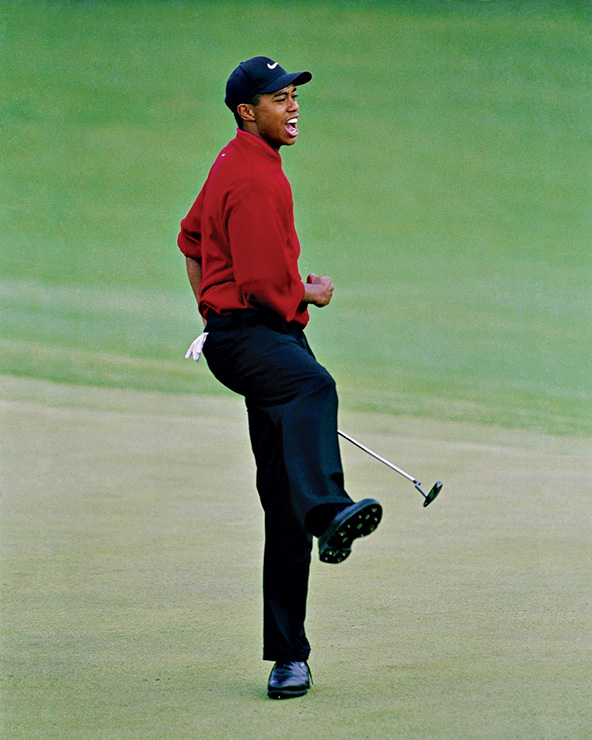

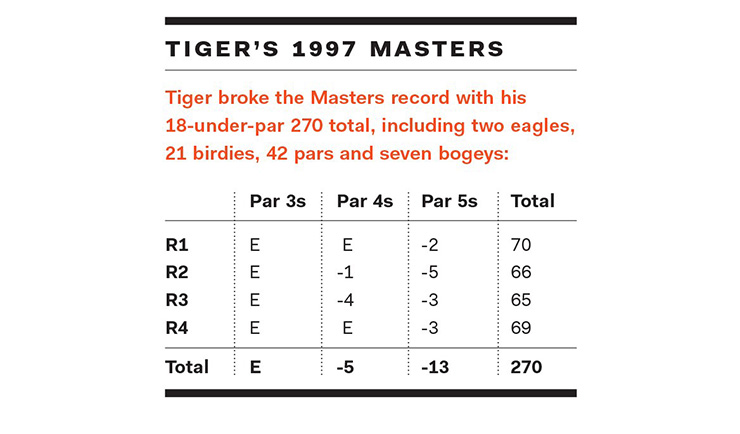

After a puzzling first-nine 40, Tiger played the next 36 holes in 16 under, setting scoring records for low middle 36 holes (131), low last 54 holes (200) and largest 54-hole lead (nine strokes). His 12-stroke margin of victory bested Jack Nicklaus’ mark, set in 1965, by three shots.

Photo by Golf Digest Archive

They were sitting together the year before—or maybe it was the year before that—at the Golf Digest house in Augusta, balancing paper plates of barbecue and beans on their knees, eavesdropping on a discussion of Opens and Invitationals in golf. “Invitationals,” Tiger said under his breath, not bitterly, just matter-of-factly, “were the ways around the Opens.”

Largely depending on how much homework he brought from Stanford, Woods made and missed his two amateur cuts at Augusta. Staying under a sun-streaked cupola in a clubhouse garret known as the Crow’s Nest, Tiger was unable to sleep (“I’ve never been any good at sleeping,” he said), getting up in the middle of the night to prowl the unfamiliar corridors and commune with the well-known ghosts. “The shadows there roll all around the walls,” he said. “That attic is haunted.”

Afraid to switch on any lights, Tiger stumbled into what turned out to be the Champions Locker Room. He sat in the dark in front of 1956 winner Jackie Burke’s locker and reviewed the journey.

Woods was born in 1975, the year Lee Elder broke the four-decade-long color line at the Masters. In 1974, chairman Clifford Roberts greeted the press with the hope that former Augusta caddie Jim Dent would soon win a PGA Tour event and become eligible to play in the tournament, a criterion established in 1972.

Roberts and Bobby Jones might not have been any more bigoted than the average American born in 1894 or 1902, but neither was a champion of affirmative action. They weren’t alone in that. The Professional Golfers’ Association of America didn’t scrub the hateful phrase “professional golfers of the Caucasian race” out of its Constitution until 1961, making the saddest line in a media guide this one after Charlie Sifford’s name: “turned professional-1948; joined PGA Tour-1961.”

Of course, Masters champions as a group could have invited Sifford or anyone else to compete in the tournament—they controlled one slot. In 1969, when 46-year-old Sifford followed up his Greater Hartford Open title of a couple of years earlier by winning the Los Angeles Open (the same day the Jets beat the Colts in the Super Bowl), ’59 Masters champion Art Wall Jr. tried marshaling support for Sifford among his colleagues. Charlie received just a solitary vote: Wall’s.

Elder came to the 1997 Masters on Sunday, by which time everyone knew what was about to happen, because he wanted to be there. Sifford did not come because he didn’t want to be there. He sent Tiger a fax, though: “Don’t fire at all the pins. Be cautious. Be smart. Play the golf course. But when the time comes, let it go. Turn it loose. Be strong. Be yourself.”

A BOOST AND A DIG FROM MARKO

Woods followed the chip-in at 12 on Thursday with a birdie at the par-5 13th to get back to one over. He parred 14, and then, in a pileup of twosomes, reached the tee at the par-5 15th, where O’Meara was just ahead of him in the queue.

Tiger’s tightest bond on tour was with the Florida neighbor he called “Marko,” whose wife, Alicia, told her husband, “That poor kid is sitting over there in his house all alone. Let’s get him over here for dinner.” Mark said, “Tiger had a nice car he hadn’t washed in about a year. I called him up and said, ‘Bring that filthy thing over here, will you? I’m doing my cars. I’ll wash it. I’ll wax it.’ ” That was the beginning of their friendship.

“Marko became a big brother to me,” Woods said. “He taught me a lot of off-the-course things, or tried to. Some of those things, like how to deal with the media, didn’t completely take. But I wouldn’t have ever had the success I had early on without his help.”

“He hit this bullet, taking this ridiculous line down the left between this really tall tree and a shorter one. The ball just went extra fast and kept climbing.” —Paul Azinger describing seeing Tiger’s swing.

Photo by Golf Digest Archive

On a small wood bench at the 15th tee, Tiger took a seat to wait out the delay, and O’Meara joined him. Nothing was said for about a minute. The week before, as Mark was handing over the $65 he lost to the 59, Tiger had ragged him, in their usual way, “Geez, Mark, what did you shoot, around 87?” Now, in what amounted to a delayed rejoinder, O’Meara said in mock exasperation, “Why don’t you just pretend you’re playing against me? I’m still waiting for you to play bad against me.”

Tiger eagled 15 (his second shot was a mere pitching wedge to six feet). He was under par. Then he birdied 17. The 40 had been overturned by a 30 to get him within three strokes and two players of John Huston’s lead. Faldo said, “Although I had played part of a practice round with Tiger in 1995, now I truly understood what all the excitement was about. He was quite something.”

“Nick and I talk more than you’d think on a golf course,” Woods said, “or more than he does with most people, I hear. I don’t know if it’s just me, but he has things to say [though not this week, 75-81, missing the cut]. You know, just briefly. Just comfortably. He’s a good guy to play with.”

Friday, Tiger traded Faldo for Paul Azinger, who was also operating mainly on hearsay. “I’d never seen him hit a shot in person,” Azinger said, and being immersed in his own double bogey at 1, Paul still had not seen Woods make a live strike until Tiger’s drive at the par-5 second.

“The sensation was kind of otherworldly,” Zinger said. “I mean, he hit this bullet, taking this ridiculous line down the left between this really tall tree and a shorter one. The ball just went extra fast and kept climbing. It stayed in the air forever, until it finally disappeared down the hill to some spot where probably no one had ever been before.” Azinger and his caddie just looked at each other and laughed.

Tiger shot 66 that day (to 73 for Paul). At 13, Woods made another eagle (with an 8-iron to 20 feet), and Jim Nantz, a telecaster with a sense of history, told CBS sidekick Ken Venturi, “Kenny, let the record show, a little after 5:30 on this Friday, April 11, Tiger takes the lead for the very first time in the Masters.”

At day’s end, Woods led Scotsman Colin Montgomerie by three strokes, and said goodbye to Azinger and hello to Monty.

The gallery was 10-deep, all trying to get a close-up look at the phenom. Not only were the Patrons entranced: Masters Sunday garnered a 15.8 overnight rating, which CBS claimed as a record for a golf major.

Photo by Golf Digest Archive

Also known as Mrs. Doubtfire and Billy Bunter, Montgomerie managed to win eight Orders of Merit and still be the leading target for irreverence on the European Tour. Apple-cheeked and curly-haired, he was the Gerber baby all grown up. British schoolboy “Billy Bunter” is a U.K. cartoon character, obnoxious, corpulent (particularly enamored of sticky buns), obtuse, self-important, conceited and positive that he is always right.

“The pressure is mounting,” Montgomerie said Friday night, “and I have a lot more experience in major championships.”

“That definitely motivated me,” Woods said. “He had more experience [in majors], no doubt about that. [Everyone did; this was Tiger’s first as a pro.] But he hadn’t won a major, and neither had I. If someone who had won major championships had said that, then I would have let it pass. But since he hadn’t won one either, I thought we were on a clean slate.”

Tiger shot 65 this time, to 74 for Montgomerie, who at the back door of the interview room was offered a dispensation but insisted on testifying. It would be the most appealing appearance of his major-less career.

“All I have to say,” he said with a chastened smile, “is one brief comment today. There is no chance. We’re all human beings here . . . [but] there’s no chance humanly possible that Tiger is going to lose this tournament. No way.”

Probably thinking of the 11-shot swing between Greg Norman (“Dead Man Walking”) and Faldo only 12 months before, someone asked, “What makes you say that?”

“Have you just come in?” Montgomerie replied with a sigh. “Have you been away? Have you been on holiday?”

Monty knew that Woods hit the ball “long and straight.” He was aware that Tiger’s iron shots were “very accurate.” But he had no idea that anyone could putt like this. “When you add it all together,” he said, “Tiger is nine shots clear [of Italian Costantino Rocca], and I’m sure that will be higher tomorrow.”

After all, “Faldo is not lying second,” and “Greg Norman is not Tiger Woods.”

‘There’s no chance humanly possible that Tiger is going to lose this tournament. No way.’ — Colin Montgomerie, after shooting 74 to Woods’ 65 in the third round

FINISHING THE RACE

Muhammad Ali, on his off nights, could look a little blotchy. In the ring before the opening bell, his complexion sometimes tipped what was to come. But against George Foreman in Africa, standing alone in one corner, waiting out Zaire’s interminable anthem, Ali gleamed like a copper kettle. That’s what Tiger looked like Sunday morning.

Late the night before, as they shared a bowl of ice cream, Earl advised his son, “This is going to be the hardest round of golf you’ll ever play, and the most rewarding.”

“When I arrived,” said Elder, who was 62, “Tiger had just left the practice range. I told him, ‘Just do what you’ve been doing all week, and things will work out.’ Embracing Lee, Woods whispered, “Thanks for making this possible.” Then, on his way from the practice putting green to the first tee, he prodded himself: Finish the race. For the next four hours, Tiger rethought those three words over and over.

Sunday’s score was a prudently commercial 69, nearly risk-free if you don’t count the narrowly avoided calamity of a small boy in the gallery who reached up for Woods in the middle of a ferocious swing. And yet, the lead swelled by three strokes. The Masters record of 271 by Nicklaus (1965) and Raymond Floyd (’76) was trimmed by a shot, and the runner-up, Tom Kite, lost by 12. Only Old Tom Morris had ever won a major by as much as 13, in the 1862 Open Championship at Prestwick, Scotland. (Young Tom won one by 12.) In his professional debut, Woods was already reaching back to shepherds and crooks.

First in driving distance (323.1 yards on average, a full 25 yards beyond the next-best, Scott McCarron); tied for first in greens in regulation (with Kite and Fred Funk, 55 of 72); and recording zero three-putts, Tiger shook the very geometry of golf, pushing not just the envelope but the boundaries, the capacities, of the National. His normal approach clubs weren’t normal:

No.1 400-yard par 4: driver, pitching wedge.

No.2 555-yard par 5: driver, 8-iron.

No.3 360-yard par 4: driver, 15-yard chip.

No.4 205-yard par 3: 6-iron.

No.5 435-yard par 4: driver, pitching wedge.

No.6 180-yard par 3: 9-iron.

No.7 360-yard par 4: 2-iron, pitching wedge.

No.8 535-yard par 5: driver, 2-iron.

No.9 435-yard par 4: 3-wood, pitching wedge.

No.10 485-yard par 4: 2-iron, 8-iron.

No.11 455-yard par 4: driver, pitching wedge.

No.12 155-yard par 3: pitching wedge.

No.13 485-yard par 5: driver, 8-iron.

No.14 405-yard par 4: driver, pitching wedge.

No.15 500-yard par 5: driver, pitching wedge.

No.16 170-yard par 3: 9-iron.

No.17 400-yard par 4: 3-wood, sand wedge.

No.18 405-yard par 4: driver, sand wedge.

Eleven wedges into 18 greens, and every par 5 reachable in two.

Woods caps the first of his four Masters titles.

Photo by Augusta National

Rocca said, “He hit a 6-iron into the wind [at the par-3 fourth] when I hit a 1-iron, and his drive was so long at 8, he had only a 4-iron to the green. He pulled it a little left, and, again with the 4-iron, hit a low, running shot to two feet for birdie. Two 4-irons in a row. Very different.” (Rocca shot 75, but his long day of hearing “Down in front!” wasn’t wasted. Come September, at Valderrama in Spain, the Europeans would beat the Americans in another Ryder Cup, and Costantino would defeat Woods in the singles, 4 and 2.)

To Tiger, how he had won the ’97 Masters wasn’t a bit complicated. “The majority of my putts were uphill,” he said, “because I was able to control my irons into the greens. Why was I able to do that? Because I had short irons into the greens. Why did I have those short iron shots? Because I drove the ball great. And putting was just a reflection of everything working, from the tee box to the green. Or from the green to the tee box, if you think about it. My dad always taught me to think every golf course backward.”

Tiger climbed up the hill from the 18th green straight into Earl’s arms. “My favorite shot of the day,” President Clinton said on the telephone, “was that last shot with your dad.”

At his home in Kingwood, Texas, Sifford said, “It put the Masters to rest for me. You know, it’s 50 years [practically to the day] since Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line. Whenever Tiger tips his cap on the golf course, I consider that to be recognition to the unrecognized. And, when he hugged his daddy at the end, I shed a few tears. Watching Tiger walk up the final hole, I felt like I was part of him. He did what I wanted to do but didn’t have the chance—I was too doggone old. Starting out, I wanted four things: to play in a PGA tournament, to play in a National Open, to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, and to play in the Masters. I got three out of the four, so that ain’t too bad.”

Tiger gets a hand from 1996 Masters winner Nick Faldo. Photo by Augusta National/Getty Images

More than 44 million people watched on television, the biggest TV audience ever counted for a golf tournament. Away from the golf, a major and a minor tragedy hung over the grounds. When the price of scalped badges shot up to $7,000 apiece, local businessman Allen F. Caldwell III couldn’t make good on 70 tickets he had promised some big shots. He killed himself with a 12-gauge shotgun.

Nineteen-seventy-nine Masters and 1984 U.S. Open champion Fuzzy Zoeller, trying to be funny for a television crew, warned Woods off serving fried chicken at the next Champions Dinner. “Or collard greens,” Zoeller said, “or whatever the hell they serve.”

(“My Tiger have no idea what collard greens are,” his mother, Tida, said.)

Zoeller’s mortal sin was the word “they.” That was something inside Fuzzy, or around him, or around all of us, that just slipped out. (It’s always slipping out, isn’t it?) That cost a pretty good guy a contract with Kmart and a legacy of laughter.

In the Butler Cabin (not named for the butlers), Faldo helped Tiger into the green jacket, the first of four. Woods would have bigger and better tournaments, believe it or not, but none as important. At the 2000 U.S. Open, when Tiger won by 15 strokes, Old Tom’s major mark of 13 wasn’t the only thing that fell. Everything tumbled that week at Pebble Beach. Willie Smith, Willie Anderson and Long Jim Barnes surrendered records to Tiger that they had held for 101, 97 and 79 years.

It was the history of the Masters, as dark as the Champions Locker Room in the middle of the night, that made 1997 more important. Also, the green jacket is a more tactile prize than the largest silver loving cup.

Back at the rented house, celebrating with friends and family, Earl went looking for Tiger and found him in his bedroom asleep (“I’ve never been any good at sleeping”) fully clothed with his arms wrapped around the green jacket. “Cuddling it,” as Tiger said, “like it was a little bear.”

And, a year later, he put it on Mark O’Meara.