By John Strege

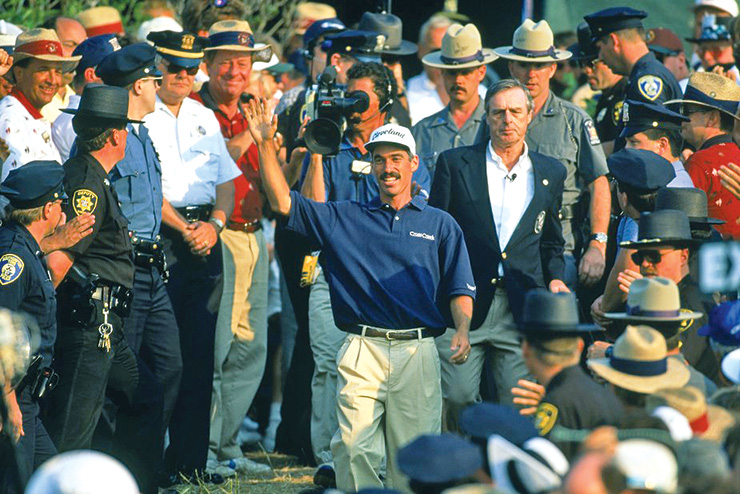

Corey Pavin, at 5-foot-9 and 140 pounds, never was going to stand out in a crowd, though he does so now symbolically. He is a relic of sorts, a welterweight once capable of holding his own against heavyweights, guile and grit with his one-two punch. He stands as a testament to where the game was and where it is now.

Twenty-three years have passed since he took down one of golf’s bona fide heavyweights, Greg Norman, on two of golf’s greatest stages, the U.S. Open and Shinnecock Hills.

He delivered a knockout punch with a 4-wood from the fairway at the 450-yard par-4 18th hole, 209 yards to the front, 228 to the hole, a clutch shot that still resonates today, on the eve of another U.S. Open at Shinnecock.

“I was one up with that shot to go,” he said recently. “Greg Norman and Tom Lehman were two holes behind me. In my mind, if I make par there I would very likely win. With having that in my head I had to throw that out and concentrate on the shot.”

He asked caddie, Eric Schwarz, whether he could get a 2-iron there. No, you can’t, Schwarz replied. They agreed, “100 percent,” that 4-wood was the correct club, Pavin said.

“The wind was blowing 15, 20 miles an hour right to left. I could see the top of the flag. That was it. I decided to aim at the right edge of the green and hit a little draw, the normal routing. The second I hit it I knew it was good.”

It was better than good. It was perfect, the ball stopping five feet from the hole. It clinched a U.S. Open victory, the capstone to a career worthy of Hall of Fame consideration—15 wins on the PGA Tour, one on the European Tour win, two on the Japan Golf Tour and a Ryder Cup captaincy.

Pavin, now 58, represented where the game was in 1995 with that 4-wood, a club now virtually obsolete in professional golf, and how he played the 18th hole at Shinnecock. From the tee, he worked the ball left to right into the wind with his driver to better his odds of hitting the fairway, then hit the 4-wood second shot right to left with a helping wind into the green.

Pavin was a legendary shotmaker who eschewed a linear path to the target. “It was hard for me to get up and hit a hard straight shot,” he said. “To me, it’s kind of boring.”

David Cannon

As for where the game is now, the uphill 18th hole at Shinnecock Hills has been stretched by 35 yards, its scorecard length for the Open 485 yards. What club might players be hitting into the green at this U.S. Open?

“If conditions are favourable, if it’s not playing into the wind, a guy like Dustin Johnson might be hitting driver and wedge,” Pavin said. “Maybe some guys would hit 3-wood and 8-iron.”

Clearly, the game has changed, or, for those who prefer euphemisms, it has evolved. The equipment, among other factors, has increased the emphasis on power and diminished the value of shaping shots, given the inability of the ball to spin to the same degree it once did.

Pavin, a PGA Tour Champions regular, does not necessarily lament the changes, notwithstanding the fact his skill set has been devalued as a result. He’ll never be long, and those who are long are less concerned with hitting it crooked as they once might have been.

“Guys are hitting it a lot farther. The balls go farther, the clubs go farther, players are stronger,” Pavin said. “It’s a combination of a lot of things. The ball doesn’t curve as much. It doesn’t spin as much, so it’s harder to curve. It’s just the way game’s gone. If it’s good or bad, I can’t answer that.

“Personally I’d like to see the ball come back and not go as far. Obviously, that would help me, but not for that reason. So much has to be done to golf courses now to lengthen them and change them. Courses are becoming obsolete.”

If he was, say, 32 today, would he be as competitive as he once was? “Zach Johnson is a great example,” Pavin replied. “He’s a guy who moves the ball, is not a long hitter and figures out a way to get it done.

“If I was 32 [now], I’d play a different style of golf. I would have been brought up differently. But if I played now the way I did, how would I do? The question is not answerable. You wouldn’t be using the same equipment. I would like to believe I would find a way to be competitive, that I’d figure out a way to get the ball in the hole as quickly as possible.”

Pavin’s offense is not directed at the equipment or the players, but at the USGA for having become more accommodating of how the game is played today.

“I’m a little miffed at the USGA lately with how it’s setting up courses,” he said. “I applaud them on the one hand, trying to do different things. But to me, U.S. Open golf courses have fairways 25 to 32 yards wide and long rough right off the fairway. It puts a premium in putting the tee shot in the fairway, leaving you clean iron shots into the green. That’s the U.S. Open to me.

“I’ve heard people who’ve said the fairways at Shinnecock are 40-yards-plus wide. I find that sad. It’s nice when a golf course is set up the same way over a long period of time, that it’s a constant. It’s nice to compare different eras.

“I think the great thing about the U.S. Open, in general, is that it tests all phases of your game. That’s what I love about the U.S. Open. You have to hit it straight and it tests your iron play, your short game. You have to manage your game and there are a lot of things that go into it.”

Meanwhile, there is a historic 4-wood in a display case in Pavin’s home, and one could argue that a more appropriate place for it is the World Golf Hall of Fame. But this is an argument for another day.

What is undeniable is that a wedge used to help finish off an Open victory (short of holing out for eagle), rather than taking its place in history, will remain in play until its grooves wear out.

Yes, the game has changed.