The Southport, England, native looks to please the locals by holding the claret jug at Royal Birkdale

By John Huggan

In the run-up to this week’s Open Championship at Royal Birkdale, few members of the elite field will generate more attention. Which is understandable. Playing in his home town of Southport naturally makes Tommy Fleetwood a person of interest entering the year’s third men’s major. That he’ll arrive at the course many regard as the best in England amid a run of stunning form—having risen more than 170 places in the World Rankings since last autumn—makes his story all the more intriguing.

This year alone, as well as claiming the Abu Dhabi Championship and the recent Open de France, Fleetwood has posted a string of high finishes. Most notably, the former English Amateur champion was runner-up behind World No. 1 Dustin Johnson in the WGC-Mexico Championship, second again in China’s Shenzhen International and fourth in last month’s U.S. Open, where he played alongside eventual champion Brooks Koepka in the last round. In such company, a T-6 at last month’s BMW International in Germany seems merely routine.

All of which has come about in the wake of a return to his boyhood swing coach, Alan Thompson, after a switch in March 2015 to Pete Cowen, who works with, among others, current Open champion Henrik Stenson, proved unproductive.

“I played a few practice rounds with Henrik, and I wanted to hit it like him. So I asked Pete if he could help,” Fleetwood says. “We had success early on, but I struggled with one or two moves, which affected my confidence. For whatever reason, my body wouldn’t allow me to swing the way we wanted, and we couldn’t figure out the answer.

“I changed for the right reasons though. I wanted to be a world-class player, and I went to Pete because he is arguably the best coach in the world. It just didn’t work out, but I still gained a lot from the experience. Since I went back to Alan, we’ve been able to do stuff with my swing we couldn’t do before. I used to play with a draw, but my ball flight is a lot straighter now and my swing path a lot more neutral.”

That detour in the Fleetwood career path wasn’t his first. Nor his second. To get to this point, the 26-year-old former No. 1 amateur on the planet has had to overcome a handful of obstacles put in his way.

When I started playing well all I wanted to do was win. Which was a problem. When it became clear I wasn’t going to win, I would get fed up. I played poorly on a few Sundays, finishing 50th because I wasn’t interested in finishing 30th.

On the road to Birkdale, Fleetwood had to pass—literally and figuratively—Southport’s Municipal course. It measures only 6,253 yards and plays to a standard scratch of 69, and it’s where it all began for the now 14th-ranked player in the world. “There’s a hump in the first fairway, maybe 50 yards off the tee,” he says with a smile. “I couldn’t get over it for the longest time.”

He exaggerates. Having started his love affair with the game at age 6, Fleetwood was regularly shooting in the 80s just two years later, and giving his brother, Joe, himself a former professional, a run for his decade-older money. (“One of us was an accident—not sure which,” Tommy jokes). His first handicap was 27, but he was playing off a one-handicap as a 13-year-old and plus-one a year later.

“I was a big kid who could putt well,” he says. “And I had a naturally good swing, better than it is now.”

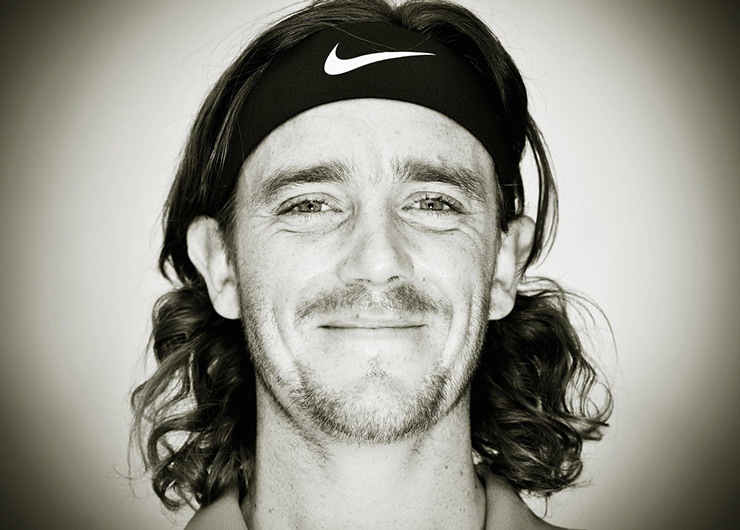

Fleetwood’s amateur days included playing for Great Britain & Ireland in the 2009 Walker Cup at Merion and a No. 1 world ranking. (Photo by David Cannon/Getty Images)

That may well be true. For long enough, Fleetwood’s rise through golf’s ranks was all but seamless. Runner-up in the British Amateur in 2008, a Walker Cup player for Great Britain & Ireland in 2009, second in a Challenge Tour event as an amateur in 2010 and No. 1 on the Challenge Tour money list in 2011, his gift for golf was obvious.

Then came 2012. Fleetwood arrived at the South African Open, his final event of the season, in 124th place on the Order of Merit. In other words, something special had to happen. And it did. Shooting a 69 in the last round, Fleetwood finished T-6 and hauled himself up a card-saving 14 places on the money list.

That week, however, was not the most important of that gloomy 2012 season, one on which he missed as many as 15 cuts.

“Everyone talks about South Africa, but for me it wasn’t the turning point of a very frustrating year,” Fleetwood says. “That came in Holland back in September. In the second round of the KLM Open, I got down in two shots from 160 yards on the 16th, then did the same from 115 yards at each of the last two holes. I made the cut on the number, then played really well on the weekend, finished T-17 and won €22,860. Without that, I would have lost my card.”

Perhaps more importantly, Fleetwood learned much about himself during those many weekends off.

“I spent a lot of time sulking,” he admits. “I wasn’t playing great. I just wasn’t ready. My short game was bad. It was the first time I had really lost form. And I didn’t know how to cope with it. So I would go home and sit in my chair and think about what I was doing wrong. I should have been out trying to fix those things. It was mostly short game. I was hitting it OK. But I had lost confidence and the ability to score. And it’s hard to get out of that rut. I would start with three birdies and still shoot two over. I couldn’t do anything right. And as you do when things are not going your way, I missed a bunch of cuts by a shot.”

Still, having glimpsed golf’s dark side for the first time, it didn’t take Fleetwood long to make the most of his narrow escape from a return to the Challenge Tour. His maiden European Tour victory came in August 2013, when he claimed the Johnnie Walker Classic at Gleneagles after a playoff with Scotland’s Stephen Gallacher and Argentina’s Ricardo Gonzalez. It was a huge boost.

Besides his two victories in 2017, Fleetwood has been in the hunt at several big tournaments, including last month’s U.S. Open where he played alongside winner Brooks Koepka and finished T-4. (Photo by Jamie Squire)

“Winning was a real breakthrough,” Fleetwood says. “Once I kept my card, that was a target. Every round I have three little targets. Maybe it is just ‘talk to myself properly’ or ‘stand up straight on the greens.’ One day I might say, ‘Don’t talk to anyone.’ On another I’ll be a lot chattier. Or I might say, ‘smile all the way round.’ Little things. But little things turn into bigger things.

“When I started playing well all I wanted to do was win. Which was a problem. When it became clear I wasn’t going to win, I would get fed up. I played poorly on a few Sundays, finishing 50th because I wasn’t interested in finishing 30th. But I’ve learned not to do that.

“It was such a relief to win. You tell yourself you can do it, but until you do you don’t know for sure. And I found out I can do it by doing what I do, not what others do. The pressure I felt trying to keep my card was actually far greater.”

These days, of course, Fleetwood has loftier goals. A Ryder Cup place in France next year is high on his priority list. But becoming the first Englishman in nearly half a century to lift the claret jug on home soil—Tony Jacklin at Royal Lytham in 1969 was last to do so—would represent the loftiest of them all.

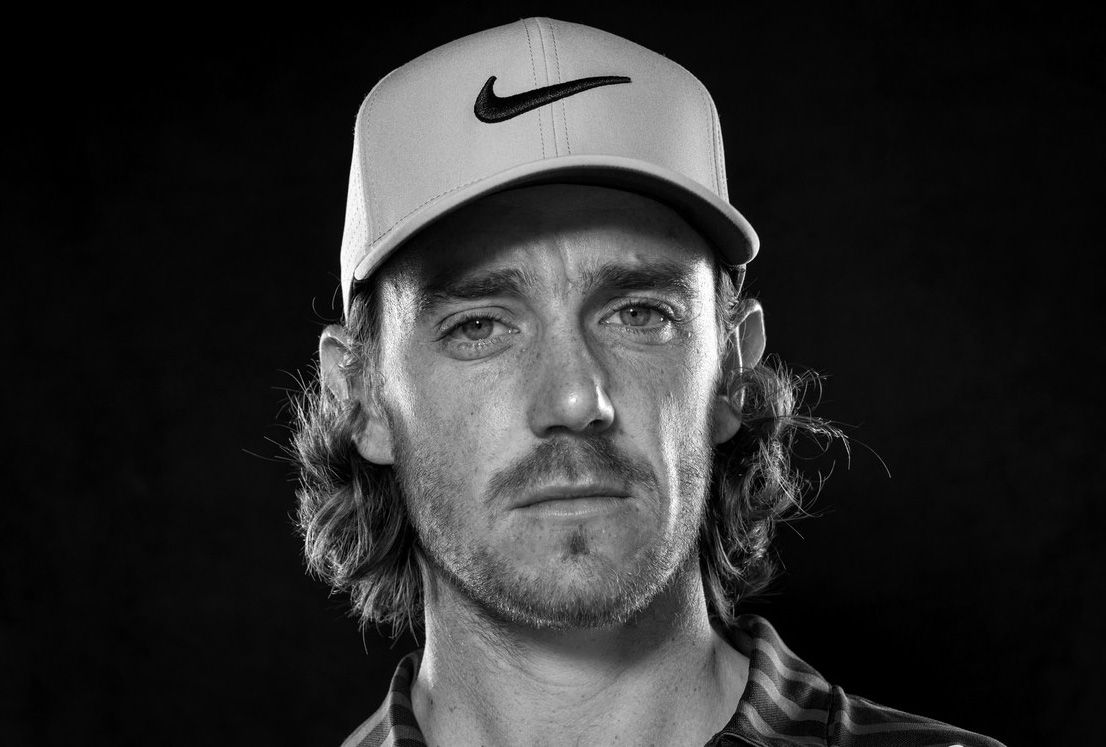

Stuart Franklin/Getty Images